Marv Levy is realizing among the advantages of turning 100 is no longer having to fudge his age.

“Well, I’d prefer to be turning 25, to tell you the truth,” the Pro Football Hall of Fame coach said, with a laugh, his distinct booming voice resonating over the phone from his hometown of Chicago last week.

Click to Gallery

FILE - Marv Levy, center, stands with Paul Hastings, left, and Greg Engelhard after it was announced that Levy would be the new head coach of the University of California, in Berkeley, Calif., Feb. 5, 1960. (AP Photo/Clarence Hamm, File)

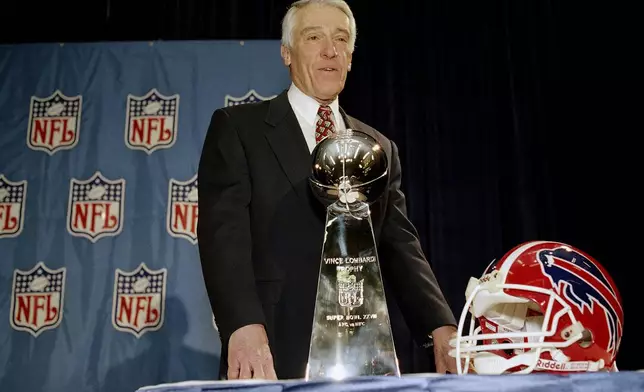

FILE- Buffalo Bills coach Marv Levy poses with the Super Bowl trophy and a Bills helmet on Jan. 28, 1994 in Atlanta following a news conference. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh, File)

FILE - Buffalo Bills head coach Marv Levy, left, is greeted by fans during the team's arrival for the Super Bowl, Jan. 24, 1993, at Long Beach, Calif. (AP Photo/Doug Pizac, File)

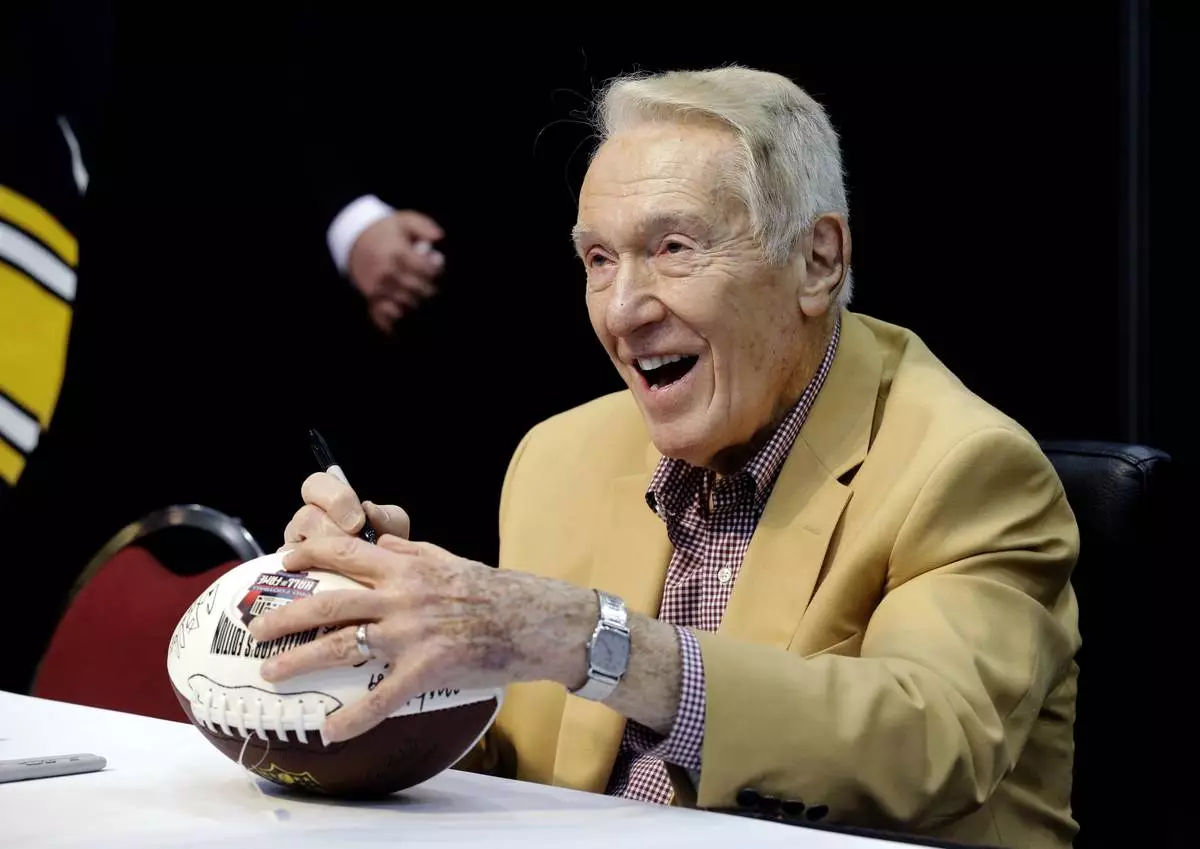

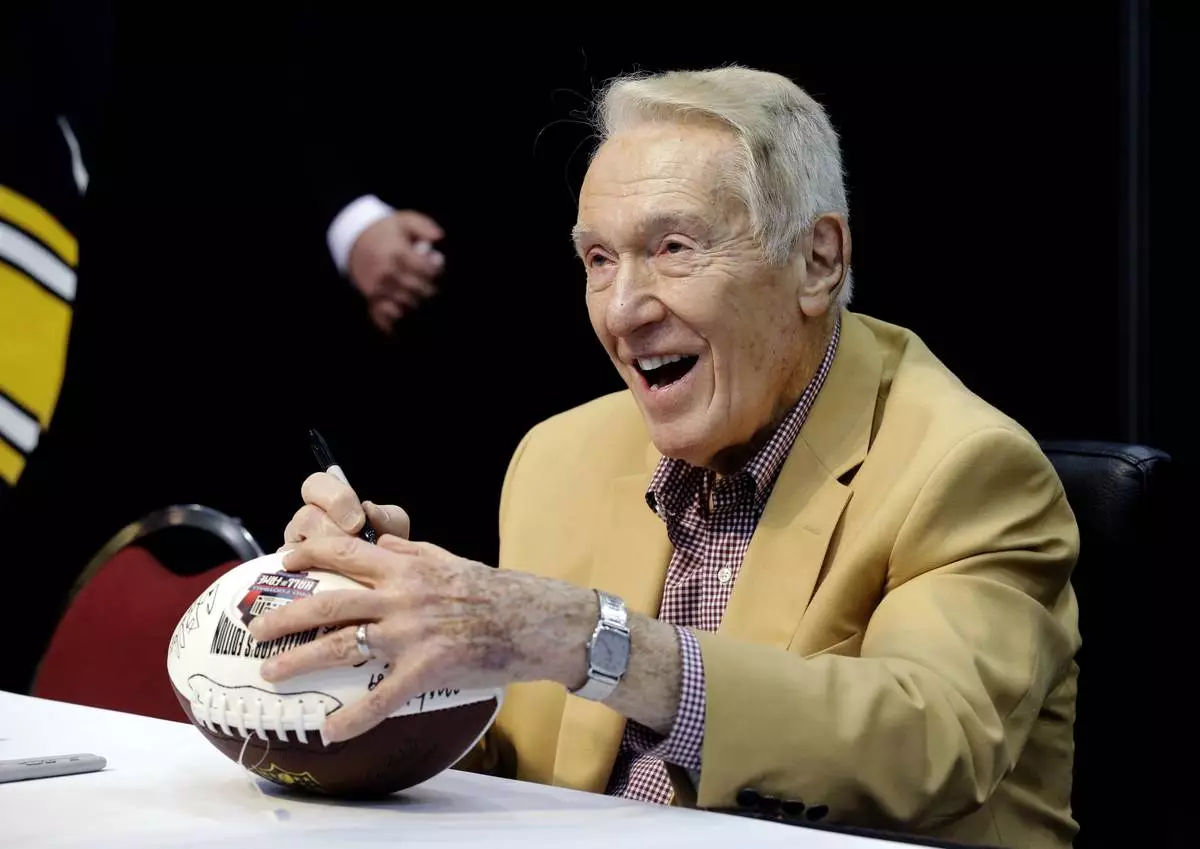

FILE - Hall of Fame coach Marv Levy signs autograph for fans at the inaugural Pro Football Hall of Fame Fan Fest on May 3, 2014, at the International Exposition Center in Cleveland. (AP Photo/Mark Duncan, File)

FILE - Buffalo Bills Hall of Fame coach Marv Levy walks on the field during warm ups before an NFL football game between the Buffalo Bills and the Miami Dolphins on Sept. 14, 2014, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Bill Wippert, File)

Acknowledging his age is actually a switch for Levy. It wasn’t until years after landing the Buffalo Bills head coaching job in 1986 when it was revealed how Levy shaved three years off his age out of fear NFL teams wouldn’t hire a 61-year-old.

“But no, I’m very appreciative,” Levy said of his milestone birthday, which is on Sunday. “I’ve been very fortunate with all the people I’ve associated with, including my dear wife Frannie and my daughter Kimberly.”

And many of those associates — family, friends, former players, coaches and executives — will all be on hand in Canton, Ohio, on Friday, when the Hall of Fame hosts a party to celebrate Levy’s 100th birthday.

He'll be arriving in first class, with officials hiring what Levy called “a special vehicle” to make the six-hour drive.

“I’m overwhelmingly complimented. It’ll be fun to see so many of my former cohorts and enemies," he said, laughing.

The list is large, in part because there’ll be plenty of Hall of Famers already there, as his birthday coincides with the annual induction festivities. This year’s class features Antonio Gates, Jared Allen, Eric Allen, and Sterling Sharpe.

Among those making the trip specifically for Levy include former players, staff, and Mary Wilson, the wife of late Bills Hall of Fame owner Ralph Wilson.

“How could you miss it? I love him so much,” Wilson said. “What a gentlemen. He’s so gracious and I admire him. I’m so happy he had this wonderful relationship with Ralph, and I’m just thrilled I can be there.”

Levy’s career dates to coaching football and basketball at Country Day School in St. Louis, Missouri, in the early 1950s, before moving on to the college ranks with stops at New Mexico, California and William & Mary.

And while he moved on to the pros and won two Grey Cup titles with the CFL Montreal Alouettes in the 1970s, Levy’s claim to greatness began with his arrival in Buffalo.

It was during his 12-year stint when Levy made a lasting impression for overseeing a star-studded Jim Kelly-led team to eight playoff appearances and four consecutive Super Bowl berths, all ending in losses.

“Fortitude and resilience. He preached that continually,” said Hall of Fame executive Bill Polian, the Bills GM who hired Levy. “That message among the many that he delivered sunk in. His sense of humor and his eloquence just captured everybody from the day he walked into the meeting room.”

Levy’s more memorable messages included citing Winston Churchill by saying, “When you’re going through hell, keep on going.”

And his most famous line, which became the title of his autobiography and a rallying cry for the Bills and their small-market fans was: “Where else would you rather be than right here, right now.”

Author, poet and avid history buff, Levy can lay claim to having seen plenty of history over the past century as someone who served in the Army Air Corps during World War II and had a front row seat in seeing the NFL become North America’s dominant sports league.

His first NFL break came as a “kicking teams” coach with Philadelphia in 1969, and he spent five seasons as the Kansas City Chiefs head coach. After retiring in Buffalo following the 1997 season, he returned to the Bills for a two-year stint as GM in 2006, with Ralph Wilson referring to the then-octogenarians as “the two golden boys,” and Levy calling himself “an 80-year-old rookie.”

Levy has outlived many of his contemporaries, from coach George Allen, whom he worked under in Washington, to AFC East rival Don Shula. He’s among the few Cubs fans who can boast outlasting the team’s World Series drought in attending their Game 7 loss in 1945, before celebrating their World Series return and title in 2016.

The one thing missing is a Super Bowl title for his beloved Bills, who have returned to prominence under coach Sean McDermott and quarterback Josh Allen. Levy likes Buffalo's chances this season, and stays in touch with McDermott, a former William & Mary player.

“I’ll take any advice he wants to give me. It’s been huge,” McDermott said. “It’s one of the great honors of coaching the Buffalo Bills is to follow a coach like Marv Levy.”

This will be Levy’s first trip to Canton in two years, when at 98, he insisted on leading the seven-block Hall of Fame Walk. He was ready to make the walk back before being coaxed into a golf cart.

And Levy has an agenda upon his return in resuming his campaign for former Bills special teams star Steve Tasker’s induction.

“Marv’s a hall of famer in every sense of the word. He’s a hall of fame human being and a hall of fame coach,” Tasker said. “And if his campaign to get me in the hall of fame keeps him alive, I hope I never get in.”

Hall of Fame historian Joe Horrigan is from Buffalo and described Levy’s era as uplifting for turning around a losing franchise and spurring a Rust Belt community struggling through an economic downturn.

“To see the legacy he has left just makes you feel good to be there,” Horrigan said of celebrating Levy's birthday. “You know, there’s no place I’d rather be than right there, right then.”

Levy is humbled by the attention, grateful people are still interested in his story, and ended the phone call with a familiar farewell: “Go Bills."

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/hub/nfl

FILE - Marv Levy, center, stands with Paul Hastings, left, and Greg Engelhard after it was announced that Levy would be the new head coach of the University of California, in Berkeley, Calif., Feb. 5, 1960. (AP Photo/Clarence Hamm, File)

FILE- Buffalo Bills coach Marv Levy poses with the Super Bowl trophy and a Bills helmet on Jan. 28, 1994 in Atlanta following a news conference. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh, File)

FILE - Buffalo Bills head coach Marv Levy, left, is greeted by fans during the team's arrival for the Super Bowl, Jan. 24, 1993, at Long Beach, Calif. (AP Photo/Doug Pizac, File)

FILE - Hall of Fame coach Marv Levy signs autograph for fans at the inaugural Pro Football Hall of Fame Fan Fest on May 3, 2014, at the International Exposition Center in Cleveland. (AP Photo/Mark Duncan, File)

FILE - Buffalo Bills Hall of Fame coach Marv Levy walks on the field during warm ups before an NFL football game between the Buffalo Bills and the Miami Dolphins on Sept. 14, 2014, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Bill Wippert, File)

Federal immigration agents deployed to Minneapolis have used aggressive crowd-control tactics that have become a dominant concern in the aftermath of the deadly shooting of a woman in her car last week.

They have pointed rifles at demonstrators and deployed chemical irritants early in confrontations. They have broken vehicle windows and pulled occupants from cars. They have scuffled with protesters and shoved them to the ground.

The government says the actions are necessary to protect officers from violent attacks. The encounters in turn have riled up protesters even more, especially as videos of the incidents are shared widely on social media.

What is unfolding in Minneapolis reflects a broader shift in how the federal government is asserting its authority during protests, relying on immigration agents and investigators to perform crowd-management roles traditionally handled by local police who often have more training in public order tactics and de-escalating large crowds.

Experts warn the approach runs counter to de-escalation standards and risks turning volatile demonstrations into deadly encounters.

The confrontations come amid a major immigration enforcement surge ordered by the Trump administration in early December, which sent more than 2,000 officers from across the Department of Homeland Security into the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. Many of the officers involved are typically tasked with arrests, deportations and criminal investigations, not managing volatile public demonstrations.

Tensions escalated after the fatal shooting of Renee Good, a 37-year-old woman killed by an immigration agent last week, an incident federal officials have defended as self-defense after they say Good weaponized her vehicle.

The killing has intensified protests and scrutiny of the federal response.

On Monday, the American Civil Liberties Union of Minnesota asked a federal judge to intervene, filing a lawsuit on behalf of six residents seeking an emergency injunction to limit how federal agents operate during protests, including restrictions on the use of chemical agents, the pointing of firearms at non-threatening individuals and interference with lawful video recording.

“There’s so much about what’s happening now that is not a traditional approach to immigration apprehensions,” said former Immigration and Customs Enforcement Director Sarah Saldaña.

Saldaña, who left the post at the beginning of 2017 as President Donald Trump's first term began, said she can't speak to how the agency currently trains its officers. When she was director, she said officers received training on how to interact with people who might be observing an apprehension or filming officers, but agents rarely had to deal with crowds or protests.

“This is different. You would hope that the agency would be responsive given the evolution of what’s happening — brought on, mind you, by the aggressive approach that has been taken coming from the top,” she said.

Ian Adams, an assistant professor of criminal justice at the University of South Carolina, said the majority of crowd-management or protest training in policing happens at the local level — usually at larger police departments that have public order units.

“It’s highly unlikely that your typical ICE agent has a great deal of experience with public order tactics or control,” Adams said.

DHS Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in a written statement that ICE officer candidates receive extensive training over eight weeks in courses that include conflict management and de-escalation. She said many of the candidates are military veterans and about 85% have previous law enforcement experience.

“All ICE candidates are subject to months of rigorous training and selection at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, where they are trained in everything from de-escalation tactics to firearms to driving training. Homeland Security Investigations candidates receive more than 100 days of specialized training," she said.

Ed Maguire, a criminology professor at Arizona State University, has written extensively about crowd-management and protest- related law enforcement training. He said while he hasn't seen the current training curriculum for ICE officers, he has reviewed recent training materials for federal officers and called it “horrifying.”

Maguire said what he's seeing in Minneapolis feels like a perfect storm for bad consequences.

“You can't even say this doesn't meet best practices. That's too high a bar. These don't seem to meet generally accepted practices,” he said.

“We’re seeing routinely substandard law enforcement practices that would just never be accepted at the local level,” he added. “Then there seems to be just an absence of standard accountability practices.”

Adams noted that police department practices have "evolved to understand that the sort of 1950s and 1960s instinct to meet every protest with force, has blowback effects that actually make the disorder worse.”

He said police departments now try to open communication with organizers, set boundaries and sometimes even show deference within reason. There's an understanding that inside of a crowd, using unnecessary force can have a domino effect that might cause escalation from protesters and from officers.

Despite training for officers responding to civil unrest dramatically shifting over the last four decades, there is no nationwide standard of best practices. For example, some departments bar officers from spraying pepper spray directly into the face of people exercising Constitutional speech. Others bar the use of tear gas or other chemical agents in residential neighborhoods.

Regardless of the specifics, experts recommend that departments have written policies they review regularly.

“Organizations and agencies aren’t always familiar with what their own policies are,” said Humberto Cardounel, senior director of training and technical assistance at the National Policing Institute.

“They go through it once in basic training then expect (officers) to know how to comport themselves two years later, five years later," he said. "We encourage them to understand and know their training, but also to simulate their training.”

Adams said part of the reason local officers are the best option for performing public order tasks is they have a compact with the community.

“I think at the heart of this is the challenge of calling what ICE is doing even policing,” he said.

"Police agencies have a relationship with their community that extends before and after any incidents. Officers know we will be here no matter what happens, and the community knows regardless of what happens today, these officers will be here tomorrow.”

Saldaña noted that both sides have increased their aggression.

“You cannot put yourself in front of an armed officer, you cannot put your hands on them certainly. That is impeding law enforcement actions,” she said.

“At this point, I’m getting concerned on both sides — the aggression from law enforcement and the increasingly aggressive behavior from protesters.”

Law enforcement officers at the scene of a reported shooting Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

Federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

People cover tear gas deployed by federal immigration officers outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)

A man is pushed to the ground as federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/John Locher)

A woman covers her face from tear gas as federal immigration officers confront protesters outside Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Adam Gray)