LOS ANGELES (AP) — Erik Menendez was denied parole Thursday by a California board that said his continued misbehavior during decades in prison for murdering his parents with his older brother in 1989 showed he is still a risk to public safety.

A panel of two California commissioners denied Menendez parole for three years, after which he will be eligible again, in a case that continues to fascinate the public. A parole hearing for his brother Lyle Menendez, who is being held at the same prison in San Diego, is scheduled for Friday morning.

The commissioners determined that Menendez should not be freed after an all-day hearing during which they questioned him about why he committed the crime and violated prison rules. They rejected parole despite strong support from family members who have advocated for the brothers’ release for months.

“Two things can be true. They can love and forgive you, and you can still be found unsuitable for parole," commissioner Robert Barton said.

Barton said the primary reason for the decision was not the seriousness of the crime but Menendez's behavior in prison. The repeated use of a cellphone was “selfish” and a sign of Menendez believing that rules don’t apply to him, Barton said to Menendez, who was clearly visibly hurt by the decision but listened intently.

“Contrary to your supporters' beliefs, you have not been a model prisoner and frankly we find that a little disturbing,” Barton said, questioning if that meant Menendez was not entirely honest with family members about his behavior.

The parole hearings marked the closest they have come to winning freedom since their convictions almost 30 years ago.

The brothers were sentenced to life in prison in 1996 for fatally shooting their father, Jose Menendez, and mother, Kitty Menendez, in their Beverly Hills mansion. While defense attorneys argued that the brothers acted out of self-defense after years of sexual abuse by their father, prosecutors said the brothers sought a multimillion-dollar inheritance.

A judge reduced their sentences in May, and they became immediately eligible for parole.

Erik Menendez made his case to two parole commissioners, offering his most detailed account in years of how he was raised, why he made the choices he did, and how he transformed in prison. He noted the hearing fell almost exactly 36 years after he killed his parents — on Aug. 20, 1989.

“Today is August 21st. Today is the day that all of my victims learned my parents were dead. So today is the anniversary of their trauma journey," he said, referring to his family members.

The state corrections department chose a single reporter to watch the videoconference and share details with the rest of the press.

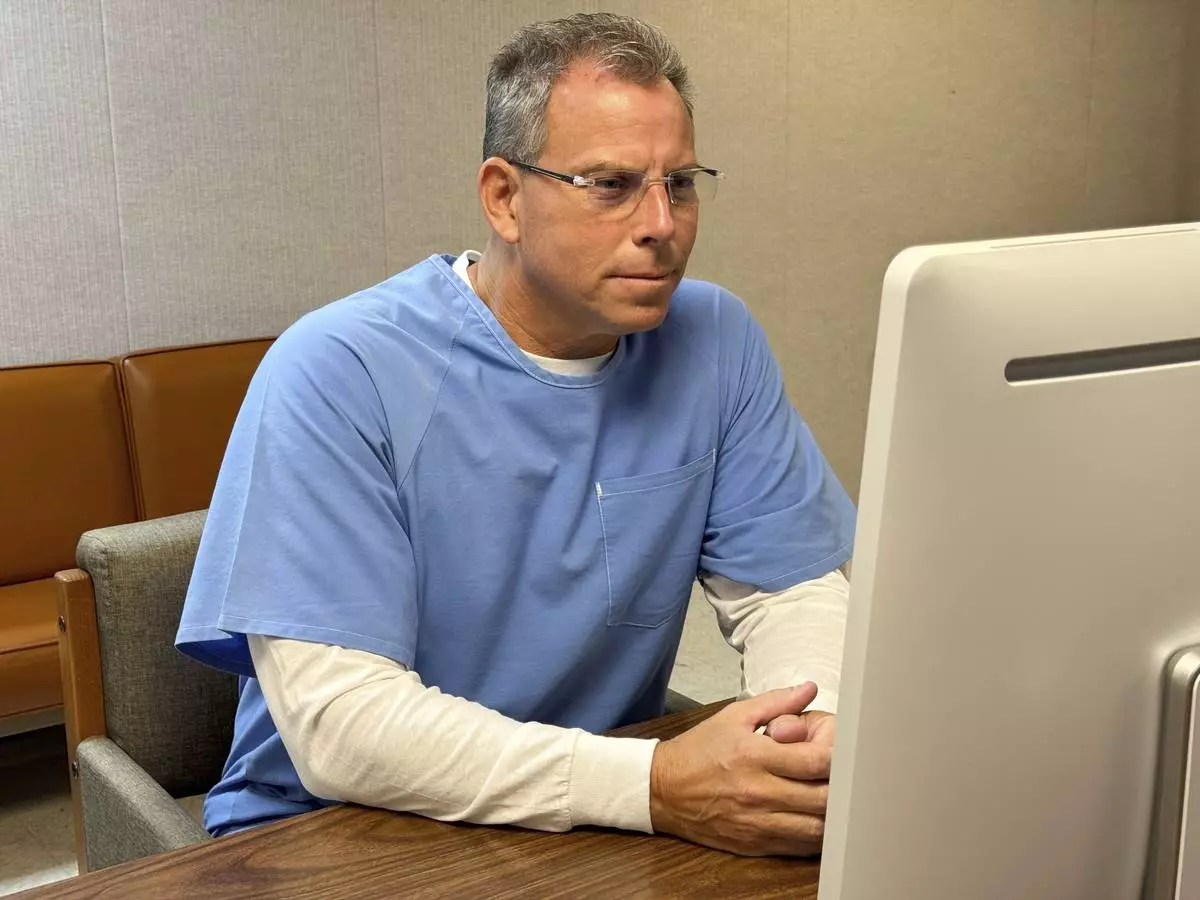

Menendez, gray-haired and spectacled, sat in front of a computer screen wearing a blue T-shirt over a white long-sleeve shirt in a photo shared by officials.

The panel of commissioners scrutinized every rules violation and fight on his lengthy prison record, including allegations that he worked with a prison gang, bought drugs, used cellphones and helped with a tax scam.

He told commissioners that since he had no hope of ever getting out then, he prioritized protecting himself over following the rules. Then last fall, LA prosecutors asked a judge to resentence him and his brother — opening the door to parole.

“In November of 2024, now the consequences mattered," Menendez said. "Now the consequences meant I was destroying my life.”

A particular sticking point for the commissioners was his use of cellphones.

“What I got in terms of the phone and my connection with the outside world was far greater than the consequences of me getting caught with the phone," Menendez said.

The board also brought up his earliest encounters with the law, when he committed two burglaries in high school.

“I was not raised with a moral foundation,” he said. “I was raised to lie, to cheat, to steal in the sense, an abstract way.”

The panel asked about details like why he used a fake ID to purchase the guns he and Lyle Menendez used to kill their parents, who acted first and why they killed their mother if their father was the main abuser.

Barton asked: “You do see that there were other choices at that point?”

“When I look back at the person I was then and what I believed about the world and my parents, running away was inconceivable," Menendez said. "Running away meant death.”

Erik Menendez's parole attorney, Heidi Rummel, emphasized 2013 as the turning point for her client.

“He found his faith. He became accountable to his higher power. He found sobriety and made a promise to his mother on her birthday,” Rummel said. “Has he been perfect since 2013? No. But he has been remarkable."

Commissioner Rachel Stern also applauded him for starting a group to take care of older and disabled inmates.

Since the brothers reunited, they have been “serious accountability partners" for each other. At the same time, he said he's become better at setting boundaries with Lyle Menendez, and they tend to do different programming.

More than a dozen of their relatives delivered emotional statements at Thursday’s hearing via videoconference.

“Seeing my crimes through my family’s eyes has been a huge part of my evolution and my growth,” Menendez said. “Just seeing the pain and the suffering. Understanding the magnitude of what I’ve done, the generational impact.”

His aunt Teresita Menendez-Baralt, who is Jose Menendez’s sister, said she has fully forgiven him. She noted that she is dying from Stage 4 cancer and wishes to welcome him into her home.

“Erik carries himself with kindness, integrity and strength that comes from patience and grace," she said.

One relative promised to the parole board that she would house him in Colorado, where he can spend time with his family and enjoying nature.

LA County District Attorney Nathan Hochman said ahead of the parole hearings that he opposes parole for the brothers because of their lack of insight, comparing them to Sirhan Sirhan, who assassinated presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy in 1968. Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom denied him parole in January 2022 because of his “deficient insight.”

During the hearing, LA prosecutor Habib Balian asked Menendez about his and his brothers' attempts to ask witnesses to lie in court on their behalf, and if the brothers staged the killings as a mafia hit. Commissioners largely dismissed the questions, saying they were not retrying the case.

In closing statements, Balian questioned whether Menendez was “truly reformed” or saying what commissioners wanted to hear.

“When one continues to diminish their responsibility for a crime and continues to make the same false excuses that they’ve made for 30-plus years, one is still that same dangerous person that they were when they shotgunned their parents,” Balian said.

Lyle Menendez is set to appear by videoconference Friday for his parole hearing. The brothers still have a pending habeas corpus petition filed in May 2023 seeking a review of their convictions based on new evidence supporting their claims of sexual abuse by their father.

The case has captured the attention of true crime enthusiasts for decades and spawned documentaries, television specials and dramatizations. The Netflix drama “ Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story " and a documentary released in 2024 have been credited for bringing new attention to the brothers.

Greater recognition of the brothers as victims of sexual abuse has also helped mobilize support for their release. Some supporters have flown to Los Angeles to hold rallies and attend court hearings.

Erik Menendez appears before the parole board via teleconference on Thursday, Aug. 21, 2025, at the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility in San Diego. (California Department of Corrections via AP)

FILE - Lyle, left, and Erik Galen Menendez sit in a Beverly Hills, Calif., courtroom, May 14, 1990. (AP Photo/Kevork Djansezian, File)

FILE - This combination of two booking photos provided by the California Department of Corrections shows Erik Menendez, left, and Lyle Menendez. (California Department of Corrections via AP, File)