SURIN, Thailand (AP) — Amnat Meephew had just enough time to pack up his clothes and flee his home in Thailand a couple of kilometers (miles) from the border with Cambodia, the second time in four months hundreds of thousands of people like him had to escape renewed fighting between the Southeast Asian neighbors.

“Sometimes when I think about it, I tear up. Why are Thais and Cambodians, who are like siblings, fighting?” the 73-year-old said. “Speaking about it makes me want to cry.”

Click to Gallery

An evacuated young girl collects food in a tent as she takes refuge in Batthkoa primary school in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia, Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025, after fleeing home following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

An evacuated elderly woman sits in a tent as she takes refuge in Batthkoa primary school in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia, Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025, after fleeing home following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

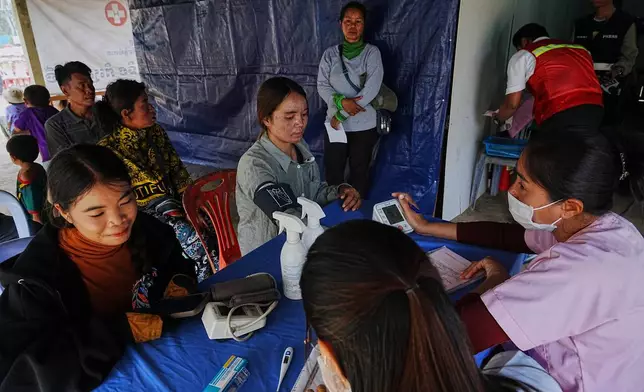

Evacuated people, left, receive medical check up as they take refuge at Batthkoa primary school in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025, after fleeing homes following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

People flee from home following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

A woman, left, walks as she takes refuge at Batthkoa primary school in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025, after fleeing from home following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

The latest round of clashes along the disputed border erupted on Monday, derailing a ceasefire pushed by U.S. President Donald Trump that ended the previous clashes in July, which killed dozens in both countries.

Officials in Thailand said Wednesday that about 400,000 people have been evacuated, while Cambodia reported more than 127,000 displaced.

Unlike during the first round of fighting in July, many Thai evacuees in northeastern Surin province said they left before hearing the sound of fire following early evacuation warnings from local leaders, triggered by a brief skirmish at the Cambodian border on Sunday.

“I could only bring my clothes,” Amnat said. “I even forgot to lock my doors when I left.”

Many took shelter in university halls, sitting or lying on thin mats, or in tents erected within their allotted space. Music played to help relieve stress. Health officials checked on evacuees, while volunteers organized activities to entertain children.

Thidarat Homhual also received a warning on Sunday to leave her home about 15 kilometers (9 miles) from the border. She teared up as she spoke about her pets she had to leave behind. Her stay in a gymnasium with more than 500 others has been far from comfortable, but she said meals are provided, and support from officials and volunteers helped her cope.

“Maybe because this isn’t the first time we’ve lived through something like this, I believe many of us can adapt. Although no one wants to adjust to living like this, I’ll just go with the flow, otherwise it would be too stressful,” she said.

Across the border in Cambodia, life for evacuees has taken on a rugged rhythm. Many said they left in a hurry after hearing shots on Monday, seeking refuge mostly in an open field.

They erected tents or improvised shelters stitched together with tarps, anchored to the backs of trucks to shield themselves from the wind. People huddled for conversation, meals or sleep. Smoke drifted from small coal stoves where families cooked simple dishes, while others went fishing in a nearby pond to supplement their food.

Loueng Soth arrived at a roadside area in the Cambodian town of Srei Snam with her seven family members. She said conditions have been difficult, and she prayed for the fighting to end as soon as possible.

“I don’t want to stay here and sleep on the ground as I do now,” she said. “I want the war to end so I can return to my home.”

With cool-season temperatures dropping, the chilling winds have made life in the same field even harder for Thai Chea, who on Monday fled his home just a few hundred meters (feet) from the battleground. At the shelter where he is staying, people donned sweaters and gathered around cooking stoves in the early morning to keep warm.

But there is still no sign of when evacuees can return home, as leaders on neither side appear willing to back down.

“I want the war to end as soon as possible, so that I can go back to my home to do my farming work and take care of my dogs and chickens. They are at home with no one looking after them,” Thai Chea said.

——

Sopheng Cheang reported from Srei Snam, Cambodia.

An evacuated young girl collects food in a tent as she takes refuge in Batthkoa primary school in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia, Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025, after fleeing home following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

An evacuated elderly woman sits in a tent as she takes refuge in Batthkoa primary school in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia, Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025, after fleeing home following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Evacuated people, left, receive medical check up as they take refuge at Batthkoa primary school in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025, after fleeing homes following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

People flee from home following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

A woman, left, walks as she takes refuge at Batthkoa primary school in Oddar Meanchey province, Cambodia Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025, after fleeing from home following a fighting between Thailand and Cambodia over territorial claims. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

ROME (AP) — Italian food is known and loved around the world for its fresh ingredients and palate-pleasing tastes. On Wednesday, the U.N.'s cultural agency gave foodies another reason to celebrate their pizza, pasta and tiramisu by listing Italian cooking as part of the world’s “intangible” cultural heritage.

UNESCO added the rituals surrounding Italian food preparation and consumption to its list of the world’s traditional practices and expressions. It's a designation celebrated alongside the more well-known UNESCO list of world heritage sites, on which Italy is well represented with locations like the Rome's Colosseum and the ancient city of Pompeii.

The citation didn’t mention specific dishes, recipes or regional specialties, but highlighted the cultural importance Italians place on the rituals of cooking and eating: the Sunday family lunch, the tradition of grandmothers teaching grandchildren how to fold tortellini dough just so, even the act of coming together to share a meal.

“Cooking is a gesture of love, a way in which we tell something about ourselves to others and how we take care of others,” said Pier Luigi Petrillo, a member of the Italian UNESCO campaign and professor of comparative law at Rome’s La Sapienza University.

“This tradition of being at the table, of stopping for a while at lunch, a bit longer at dinner, and even longer for big occasions, it’s not very common around the world,” he said.

Premier Giorgia Meloni celebrated the designation, which she said honored Italians and their national identity.

“Because for us Italians, cuisine is not just food or a collection of recipes. It is much more: it is culture, tradition, work, wealth,” she said in a statement.

It’s by no means the first time a country’s cuisine has been recognized as a cultural expression: In 2010, UNESCO listed the “gastronomic meal of the French” as part of the world’s intangible heritage, highlighting the French custom of celebrating important moments with food.

Other national cuisines and cultural practices surrounding them have also been added in recent years: the “cider culture” of Spain’s Asturian region, the Ceebu Jen culinary tradition of Senegal, the traditional way of making cheese in Minas Gerais, Brazil.

UNESCO meets every year to consider adding new cultural practices or expressions onto its lists of so-called “intangible heritage.” There are three types: One is a representative list, another is a list of practices that are in “urgent” need of safeguarding and the third is a list of good safeguarding practices.

This year, the committee meeting in New Delhi considered 53 nominations for the representative list, which already had 788 items. Other nominees included the Swiss yodelling, the handloom weaving technique used to make Bangladesh’s Tangail sarees, and Chile’s family circuses.

In its submission, Italy emphasized the “sustainability and biocultural diversity” of its food. Its campaign noted how Italy’s simple cuisine valued seasonality, fresh produce and limiting waste, while its variety highlighted its regional culinary differences and influences from migrants and others.

“For me, Italian cuisine is the best, top of the range. Number one. Nothing comes close,” said Francesco Lenzi, a pasta maker at Rome’s Osteria da Fortunata restaurant, near the Piazza Navona. “There are people who say ‘No, spaghetti comes from China.’ Okay, fine, but here we have turned noodles into a global phenomenon. Today, wherever you go in the world, everyone knows the word spaghetti. Everyone knows pizza.”

Lenzi credited his passion to his grandmother, the “queen of this big house by the sea” in Camogli, a small village on the Ligurian coast where he grew up. “I remember that on Sundays she would make ravioli with a rolling pin.”

“This stayed with me for many years,” he said in the restaurant's kitchen.

Mirella Pozzoli, a tourist visiting Rome’s Pantheon from the Lombardy region in northern Italy, said the mere act of dining together was special to Italians:

“Sitting at the table with family or friends is something that we Italians cherish and care about deeply. It’s a tradition of conviviality that you won’t find anywhere else in the world.”

Italy already has 13 other cultural items on the UNESCO intangible list, including Sicilian puppet theatre, Cremona’s violin craftsmanship and the practice moving of livestock along seasonal migratory routes known as transhumance.

Italy appeared in two previous food-related listings: a 2013 citation for the “Mediterranean diet” that included Italy and half a dozen other countries, and the 2017 recognition of Naples’ pizza makers.

Petrillo, the Italian campaign member, said after 2017, the number of accredited schools to train Neapolitan pizza makers increased by more than 400%.

“After the UNESCO recognition, there were significant economic effects, both on tourism and and the sales of products and on education and training,” he said.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

FILE -Eugenio Iorio bakes a pizza at a restaurant in Naples, Italy, Saturday, Nov. 14, 2020. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)