JEDDAH, Saudi Arabia (AP) — Arab female film directors have helped change the landscape of Arab cinema in recent years, presenting stories that haven't been told before and claiming space in an industry in a region that rarely makes room for women to grow.

Four influential female directors took part in this year's Red Sea Film Festival in Jeddah, paving the way for more diverse narratives in Arab cinema.

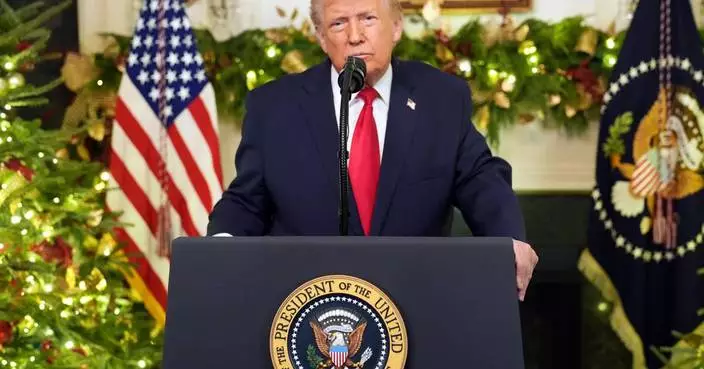

The festival, bringing together 38 directors, showcases Saudi Arabia's heavy investment in film, gaming and sports as part of its broader transformation efforts. Some rights groups have criticized these actions, saying they serve to draw away attention from the kingdom’s human rights record, including its high rate of executions and restrictions on free expression.

Palestinian American filmmaker Cherien Dabis premiered her new film “All That’s Left of You,” a multigenerational story tracing one family’s experience from the 1948 Nakba, Arabic for catastrophe, the mass expulsion of Palestinians before and during the Arab-Israeli war that followed Israel’s establishment, to 2022. The film deals with themes of Palestinian displacement and personal loss.

“It tells the story of one family over three generations and how they survive the Nakba in 1948 and the ongoing occupation,” she said. “It gives people context for how we got to where we are today and shows how much Palestinians have had to endure throughout the decades.”

Dabis, born and raised in the United States to Palestinian-Jordanian parents, said her passion and inspiration to become a filmmaker grew from a lack of authentic Arab and Palestinian representation in Western media. “I became aware that I wanted to go into storytelling in order to tell our authentic stories, because I couldn’t find us anywhere,” she said.

She said growing up in the U.S. offered better opportunities for a career in cinema than the Arab world, but the racism her family faced reinforced her desire to challenge harmful stereotypes. “My experience in the diaspora is really what compelled me to become a storyteller,” she said.

And she still struggled to be taken seriously, feeling pressure to adopt a more authoritative, even masculine tone to counter assumptions about women directors. "There is this image of women filmmakers as overly emotional or unable to command a set,” she said. “A lot of us felt we had to overcome these unfair ideas.”

Her film “All That’s Left of You” won the Silver Yusr Feature Film award, which comes with a $30,000 prize, at the Red Sea Film Festival.

Saudi filmmaker Shahad Ameen emerged as one of the standout voices at this year’s festival. Her latest film, “Hijra," won the Yusr Jury Prize, marking another milestone in her career.

“Hijra” tells the story of three women — a grandmother and her two granddaughters — on a journey from Taif to Mecca to perform Hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage. When one of the granddaughters suddenly disappears in the desert, the film follows the search for her across southern Saudi Arabia.

Ameen traces her passion for filmmaking back to her childhood, inspired by the historical television dramas that once dominated Arab screens. “I felt that as Arabs, we need to make our voices heard by ourselves, not have someone else speak on our behalf," she said.

Ameen said the changes unfolding in Saudi Arabia and the growth of the Red Sea Film Festival have directly shaped her journey in filmmaking. “Ten years ago, we couldn’t have dreamed of this,” she said, calling the festival a turning point for cinema in the kingdom.

She said filmmaking remains an uncertain path for Arab women, demanding constant perseverance with no guarantees of success. “Every film is a new beginning,” she said, noting that directors must repeatedly convince investors, festivals and audiences of their vision.

Amira Diab's journey into filmmaking wasn’t traditional. A former financial investment professional based in Manhattan, she found her calling after watching “Omar," the Oscar-nominated film by Palestinian director Hany Abu-Assad — who would later become her husband. The film, and their connection, pulled her into the world of cinema.

Diab went on to study film production in Los Angeles, working with Abu-Assad as a producer. She directed two short films and collaborated with her husband on a series. One of her breakout moments came with the short film “As a Husband," part of the Netflix anthology “Love, Life, and What’s Between."

The film resonated deeply with audiences for capturing the emotional duality of life in the Palestinian territories. “People told me they saw so much of themselves in it. It’s how life is in Palestine — joy turns into mourning, then back into joy. But there’s always a glimmer of hope,” she said.

Diab’s feature film “Wedding Rehearsal” began as a story rooted in the Palestinian territories but evolved to take place in Egypt — a decision she felt expanded the story’s cultural reach. “Egypt has such a rich, diverse social fabric,” she said. “And I worked with amazing people like Nelly Karim and Sherif Salama. Egypt really embraced me.”

Even though she has experience in Hollywood, Diab remains committed to telling Arab stories centered on women’s voices. “Of course women see the world differently. That’s why our voices matter,” she explained. “But it doesn’t mean men can’t write about women — it just means that certain emotional details only women can fully bring to the screen.”

Zain Duraie said her love with filmmaking began as a 10-year-old watching “Titanic” with her father in Amman, Jordan. She found herself captivated not by the love story, but by how the ship sank — how the film was made. That spark turned into a passion nurtured by school theater and later refined at the Toronto Film School.

At the Red Sea International Film Festival, Zain premiered her first feature film, “Sink,” about a mother struggling with her mentally ill son, a subject often overlooked in Arab cinema.

Duraie started her career at the bottom, taking on every role she could from production assistant, assistant director, producer, before directing her own films. “I carried heavy equipment up mountains,” she recalled. “People told me, ‘This isn’t a woman’s job,’” but that only pushed her further. “I worked in everything in filmmaking. I wanted to learn it all.”

Duraie is known for tackling deeply personal and social issues, especially around mental health and the female experience. “I love to work in the psychology of drama, and I want to tell stories about women — but break stereotypes too,” she said. She said Arab cinema is not there yet when it comes to gender inclusion.

Filmmaker Ameeria Diab poses for a portrait during an interview with The Associated Press about her early career in cinema at the Red Sea International Film Festival in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Dec. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Baraa Anwer)

Filmmaker Cherien Dabis speaks during an interview with The Associated Press about her early career in cinema at the Red Sea International Film Festival in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Monday, Dec. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Baraa Anwer)

From left, Abdallah Sada, Alaa Alasad, Mohammad Siam, Israel Banuelos, Bassam Alasad, Mohammad Nizar, director Zain Duraie, Clara Khoury, George Christopoulos, Glenn Gainor, Ghalia Hatamleh and Lara Ab attend the screening of the film "Sink" during the Red Sea International Film Festival in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Monday, Dec. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Baraa Anwer)