CHARLOTTE, N.C. (AP) — NASCAR driver Brad Keselowski, a former series champion who is now co-owner of RFK Racing, broke his right leg while on a ski trip, the team announced Friday.

Keselowski underwent surgery Thursday and doctors have told him to expect a quick recovery that will have him back for the season-opening Daytona 500 in February. He is winless in 16 starts in the showcase race as he enters the final years of his driving career.

“Life has a way of reminding you to slow down,” Keselowski posted on social media with photos of him in the hospital surrounded by his wife and children, an image of the break, and video of him using a walker. “Grateful for my family by my side, an excellent medical team, and the ability to take a few steps forward today. Focused on Daytona. Bonus — I'm now bionic!”

Keselowski did not reveal the extent of his injury, or what bones are broken.

Keselowski, who turns 42 just days before the Feb. 15 “Great American Race,” is entering his 17th full season of racing at the top Cup Series level. He spent the bulk of his career at Team Penske but purchased a stake in Roush Fenway Racing in 2022 and became an owner/driver of the rebranded team.

The organization is reeling from Thursday's fatal plane crash that killed longtime Roush driver Greg Biffle and six others, including his wife and two children. Biffle had retired by the time Keselowski joined the team.

“First and foremost, our hearts remain heavy with the news of yesterday's tragic events,” the team said. "The RFK Racing family, as well as the NASCAR community, as a whole, continues to keep those close to The Biffle Family and all those affected in our thoughts. Albeit untimely, we feel that in the interest of transparency we share RFK Racing co-owner and driver Brad Keselowski suffered a broken leg while on a ski trip with his family Thursday.”

The team called the surgery “routine” and said doctors expect a “a quick and full recovery.”

Keselowski broke his ankle in 2011 when he crashed during a test session and won a Cup Series race at Pocono just days later.

“I'm grateful to the medical team who took great care of me and for the support system around me,” Keselowski said in a statement. “I'm motivated to get back to full strength as quickly as possible and will work relentlessly to be ready for Daytona.”

Keselowski won the 2012 Cup Series championship for Penske and has 36 career victories at NASCAR's top level. He won the Xfinity Series title in 2010 and 39 races in NASCAR's second-tier series. He has won one points-paying race since leaving Penske as he works to help rebuild RFK into the once-proud organization founded by Hall of Fame team owner Jack Roush.

Chase Elliott, NASCAR’s most popular driver, missed six races in the 2023 season when he broke his leg in a snowboarding crash early in the season. Kyle Busch missed 11 races when he broke his leg in a crash at Daytona in 2015 but recovered to win the Cup championship that year.

AP auto racing: https://apnews.com/hub/auto-racing

FILE - Brad Keselowski is introduced to fans prior to a NASCAR Cup Series auto race at Charlotte Motor Speedway, May 25, 2025, in Concord, N.C. (AP Photo/Matt Kelley, File)

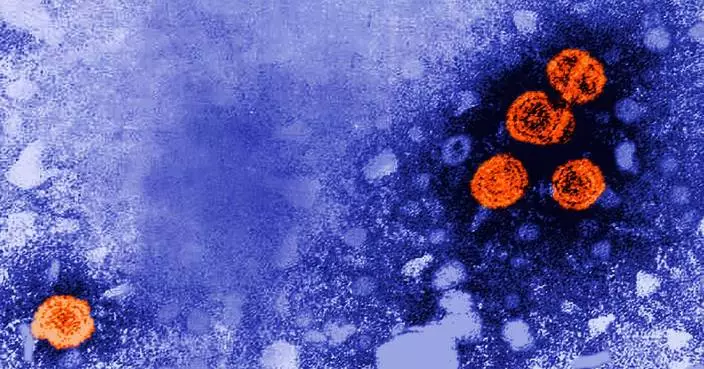

When you unlock a phone, step into view of a security camera or drive past a license plate reader at night, beams of infrared light - invisible to the naked eye — shine onto the unique contours of your face, your body, your license plate lettering. Those infrared beams allow cameras to pick out and recognize individual human beings.

Over the past decade, facial recognition technology has gone from science fiction fantasy to worldwide reality — nowhere more so than in China, home to more security cameras than the rest of the world combined.

At airports and train stations, passengers line up for face scans at gates and by officers.

On the streets, cameras scan pedestrians and flag vehicles breaking traffic rules.

By law, anyone registering new SIM cards in China must show themselves to a face scanning camera, the images stored in telecom databases. And until recently, Chinese authorities required most guests to scan their faces when checking in to a hotel.

For many, such technology has offered convenience and safety, seamlessly woven into the backdrop of their lives. But for some, it's become an intrusive form of state control.

Associated Press investigations have found that such surveillance systems in China were to a large degree designed and built by American companies, playing a far greater role in enabling human rights abuses than previously known. It has cemented the rule of China's ruling Communist Party, offering it a powerful tool to control and monitor perceived threats to the state like dissidents, ethnic minorities and even its own officials.

Dozens who spoke to AP, from Tibetan activists to ordinary farmers to a former vice mayor, described being tracked and monitored by vast networks of cameras that stud the country, hampering their movements and alerting the police to their activities.

For years, such technology faced legal barriers in the country where it was first developed, the United States. But over the past five years, the U.S. Border Patrol has vastly expanded its surveillance powers, monitoring millions of American drivers nationwide in a secretive program to identify and detain people whose travel patterns it deems suspicious, AP found.

Under the Trump administration, billions are now being poured into a vast array of surveillance systems, including license plate readers across the U.S. that have ensnared innocent drivers for little more than taking a quick trip to areas near the border.

In this series of photographs, an infrared filter was used on a modified camera converted to capture the full spectrum of light, including ultraviolet, visible, and infrared.

This filter, which cuts out some visible light to better reveal infrared, is red by design in order to block certain light wavelengths.

AP photographers on three continents snapped photos showing how these beams are used to track vehicles and people, enable facial recognition - and ultimately, assert digital control.

—

This is a documentary photo story curated by AP photo editors.

An infrared beam of light shines from a security camera watching over the Wudaoying alley in Beijing as pedestrians walk by, Oct. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

Pastor Pan Yongguang, right, and his son Paul, members of a Chinese church living in exile after fleeing from China, are illuminated by cellphone infrared facial recognition beams while sitting for a photo in the community room of the ranch compound where they're living in Midland, Texas, Oct. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Alek Schott drives past the infrared beam of an automatic license plate reader recording vehicles along Interstate 10, a route he occasionally takes for work trips, near Seguin, Texas, Oct. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

An infrared beam of light shines out of an automatic license plate reader recording vehicles passing along U.S. Highway 83, Oct. 13, 2025, in Laredo, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Dong e Li, a member of a Chinese church living in exile after fleeing from China, is illuminated by cellphone infrared facial recognition beams as she sits for a photo in her home, Oct. 13, 2025, in Midland, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

An infrared beam of light shines from a security camera watching over the Wudaoying alley in Beijing, Oct. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

Former Xinjiang government engineer Nureli Abliz, who saw firsthand how surveillance technology flagged thousands of people in China for detention, even when they had committed no crime, is illuminated by cellphone infrared facial recognition beams as he sits for a photo in Mannheim, Germany, where he's currently living in exile, July 23, 2025. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Guigiu Chen, who escaped China with her daughters after her husband, prominent rights lawyer Xie Yang, was detained, is illuminated by cellphone infrared facial recognition beams as she sits for a photo, Oct. 12, 2025, in Midland, Texas, where she's living in exile. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Infrared facial recognition beams are emitted from a cellphone held by a Uyghur man, who asked to remain anonymous for safety reasons, as he’s photographed in front of the U.S. Capitol, Oct. 16, 2025, in Washington, where he’s living in exile after escaping China. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Retired Chinese official Li Chuanliang, who openly criticized the Chinese government after seeing first-hand how surveillance technology built up the government's power and is now being accused of corruption by Beijing, is illuminated by cellphone infrared facial recognition beams as he stands for a photo in the oil fields of Midland, Texas, where he's currently living in exile, Oct. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

An infrared beam of light shines out of an automatic license plate reader as it records vehicles driving by, Oct. 13, 2025, in Laredo, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

An image of the Dalai Lama and Namkyi, a Tibetan former political prisoner who was arrested and imprisoned at 15 for protesting Chinese rule, are illuminated by cellphone infrared facial recognition beams as Namkyi sits for a photo at the Office of Tibet, Oct. 7, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Alek Schott, who filed a lawsuit alleging violations of his constitutional rights when Texas sheriff's deputies stopped and searched his vehicle at the request of Border Patrol agents, is photographed, as an infrared beam of light from a Flock Safety automatic license plate reader records passing vehicles driving near his neighborhood, Oct. 16, 2025, in Houston. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Wensheng Wen, rear right, and his wife, Lou Guangyzing, along with their children Xin, 11, from right, Gehua, 9, Jinghua, 3, Rou, 6, and Younghua, 3, members of a Chinese church living in exile after fleeing from China, are illuminated by beams of pulsed laser light from a cellphone's LiDAR scanner as they sit for a photo, Oct. 12, 2025, in Midland, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

An infrared beam of light shines out of an automatic license plate reader recording vehicles passing along U.S. Highway 83, Oct. 13, 2025, in Laredo, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Yang Guoliang, who has been under surveillance by Chinese officials after complaining about a land dispute to the central government in Beijing, is illuminated by cellphone infrared facial recognition beams as he smokes a cigarette inside his home in Changzhou in eastern China's Jiangsu Province, Sept. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

An infrared beam of light shines from a security camera watching over the Beigulou alleyway in Beijing as a pedestrian passes, Oct. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

Former Xinjiang government engineer Nureli Abliz, who saw firsthand how surveillance technology flagged thousands of people in China for detention, even when they had committed no crime, is illuminated by cellphone infrared facial recognition beams as he sits for a photo in Mannheim, Germany, where he is currently living in exile, July 23, 2025. (AP Photo/David Goldman)