Western “democracy” loves to lecture the world. The reality is its own systems sometimes spin into such obvious dysfunction that even Western media can’t pretend it’s normal.

On 21 January, The Wall Street Journal ran a piece titled “Britain’s Buffoonery Puts Mr. Bean to Shame,” bluntly saying the British government may be as incompetent as the comedy icon—just nowhere near as likeable.

The Journal’s example isn’t theory or ideology. It’s a real-world case file: a newly arrived migrant asking the state for “protection,” and a government machine that can’t—or won’t—say no.

Even the Wall Street Journal is calling it out—Britain’s dysfunction, in print.

In October 2024, a 27-year-old American landed in London claiming the US government persecuted him because he was Black, Jewish, and Mormon. He also said he needed “humanitarian protection” to avoid anti-gay violence, alleged sexual assault by US law enforcement, and then applied for political asylum in the UK.

What a “sensible” state does

The Journal asks the obvious question: what would any sensible government do with a claim like this? The truth is Britain did the opposite of “sensible”—it bankrolled the entire saga. Olabode Shoniregun, a US resident from Las Vegas, was put in a London Holiday Inn for eight months on the taxpayer tab; when told to leave, he refused, so the state moved him into government-provided housing—again paid by taxpayers.

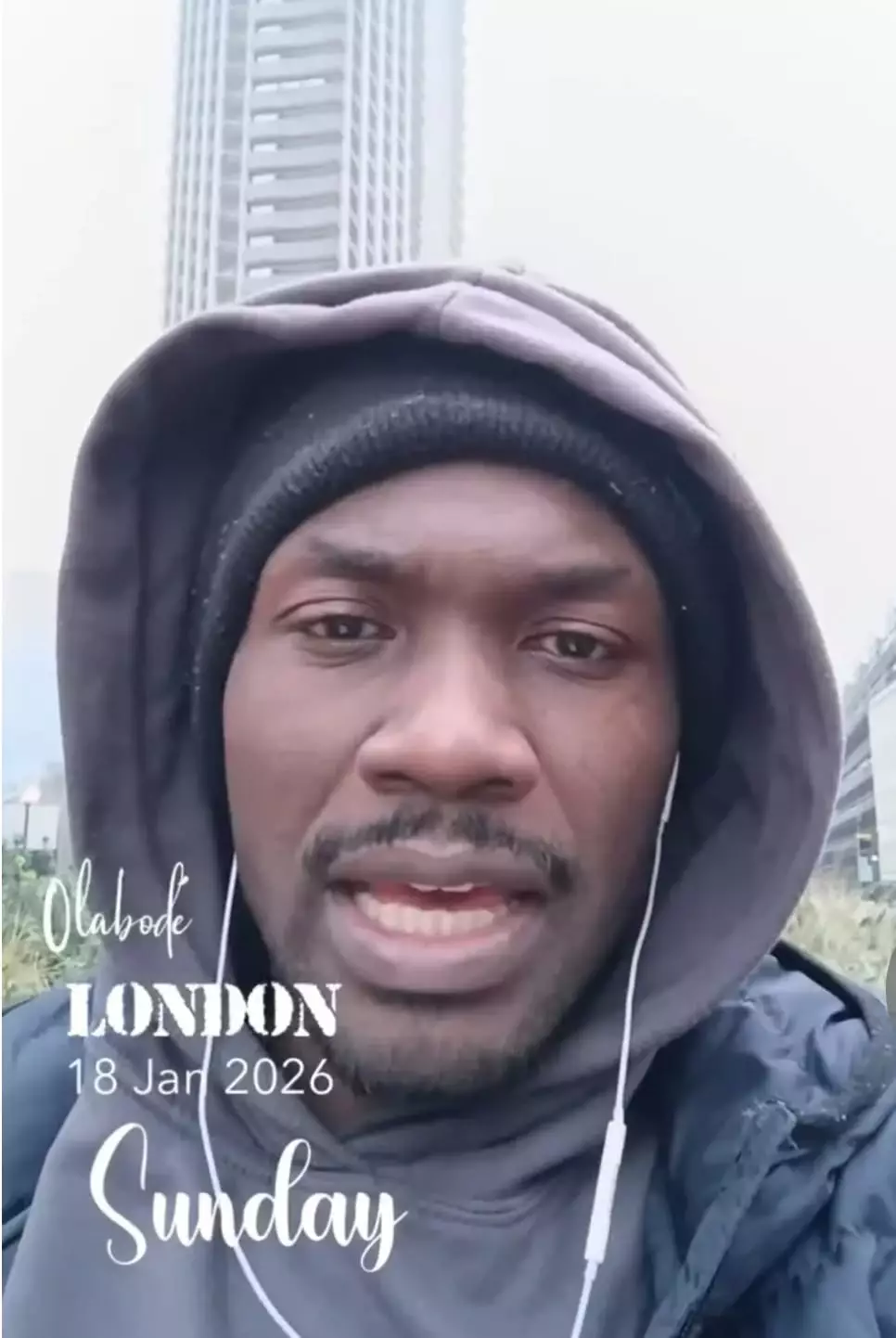

Fourteen months after arrival, Shoniregun was still in the UK. He rotated through various taxpayer-funded providers; at one point he even slept rough, yet he kept collecting £400 a month (about HK$4,200) in housing and living support.

What exposed the story wasn’t some heroic internal audit. Shoniregun documented it himself on social media—videos unboxing designer clothes in a taxpayer-funded hotel room, ordering room service, and drinking on nights out—handing the British public the evidence, directly.

Shoniregun says £400 a month isn’t enough—and demands more welfare.

The Journal then steps back and explains why people laugh at something that should make them angry: comedy often comes from incongruity—when reality clashes with what we’re supposed to expect. Like the classic parent trick: put a random object on your head and ask a child, “Is this a hat?” The child laughs because it’s obviously not.

“Absurd farce,” paid in cash

British media repeatedly called Shoniregun’s experience an “absurd farce.” And it is: forcing taxpayers to fund a prolonged, looping stay is infuriating—yet it also triggers that uneasy laughter, because you don’t expect a modern state to operate like this.

The Journal’s label for the pattern is “Mr Bean authoritarianism.” It borrows from Rowan Atkinson’s famous character—childish, incompetent, constantly creating chaos through basic lack of common sense. The point isn’t that Britain is cute and clumsy; it’s that the government performs Mr Bean-level blunders without any of Mr Bean’s harmless charm.

The Journal points to another case with the same signature: the “most expensive email in history.” In 2022, an anonymous British military staffer emailed—by accident—the identities of about 18,700 Afghans who had worked with British forces. The government response was a relocation plan costing billions of pounds, plus a court “super-injunction” that blocked reporting—and even blocked mentioning the injunction—for nearly two years. Clumsy error, heavy censorship: that’s the model.

From the government’s point of view, the Shoniregun spotlight is terrible timing, because hotel housing for asylum seekers has already triggered public fury and even unrest. In 2024, despite repeated local objections, the government spent £3.1 billion placing tens of thousands of asylum seekers in hotels; last year at least 200 residents were charged with criminal offences, including a sexual assault case in Epping that set off protests for months.

When “funny” isn’t funny

The Journal is clear: none of this is actually funny. It only feels funny because it’s so absurd—because people don’t expect a country to be governed this way, and yet real people are trapped inside the consequences.

And it wasn’t only the Journal. British media broadly followed the Holiday Inn episode, including Shoniregun’s background: father Nigerian, mother Grenadian, parents migrated to the UK; he was born in the UK but didn’t end up with UK residence rights and moved to the US at age five.

In interviews, Shoniregun didn’t exactly sound embarrassed. He argued: “I've been born in the United Kingdom, so I think that it's crazy for me not to receive some kind of benefit. So I'm not too surprised. And I don't think that £400 is a lot of cash. I deserve that and more, in my opinion.”

A country that allows this kind of Mr Bean-style episode—burning £3.1 billion on hotel placements—looks politically beyond rescue. But the real issue is the double standard: while many Britons protest the UK government approving China’s new embassy, people like Shoniregun are draining the system in plain sight.

Hong Kong fixed its loopholes

Hong Kong once had its own costly problem: a large group of “fake refugees.” With one-stop arrangements from human-rights lawyers, they filed non-refoulement claims in Hong Kong; even after rejection, they dragged cases out through legal aid and judicial reviews.

Hong Kong tightened the system: after improving the electoral system in 2021, it amended the Immigration Ordinance in 2022 to tighten vetting time limits. If the Court of First Instance refuses a judicial review, removal can be enforced even while an appeal is pending.

To stop these Mr Bean-style disasters, the key point is political structure: start by changing a system long monopolised by the opposition camp.

Lo Wing-hung

Bastille Commentary

** The blog article is the sole responsibility of the author and does not represent the position of our company. **