NEW YORK (AP) — Columbia University has named Jennifer Mnookin, the chancellor of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, as its next president as it tries to move forward from two years of turmoil that included campus protests over the Israel-Hamas war and President Donald Trump's subsequent campaign to squelch student activism and force changes at the Ivy League school.

Mnookin's appointment was announced Sunday night. She will assume her new post on July 1, becoming Columbia's fifth leader in the past four years.

The Trump administration took aim at Columbia shortly after he took office last year, making it his first target in what became a broader campaign to influence how elite U.S. universities dealt with protests, which students they admitted and what they taught in classrooms.

Immigration enforcement agents imprisoned some Columbia students who had participated in pro-Palestinian protests in 2024. The administration canceled $400 million in research grants at the school and its affiliated hospital system in the name of combating antisemitism on campus, and threatened to withhold billions of dollars more in government support.

Ultimately, Columbia reached a deal with the administration to pay more than $220 million to restore the research funds. It also agreed to overhaul the university’s student disciplinary process and apply a contentious, federally endorsed definition of antisemitism not only to teaching but to a disciplinary committee that has been investigating students critical of Israel.

Mnookin's predecessor, Nemat Shafik, resigned in August 2024 following scrutiny of her handling of the protests and campus divisions. The university named Katrina Armstrong, the chief executive of its medical school, but she resigned last March, days after Columba agreed to the settlement. The board of trustees then appointed their co-chair, Claire Shipman, as acting president while they searched for a permanent leader.

Mnookin, 58, previously served as the dean of the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law before being named to her current post at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in August 2022. She received her bachelor's degree from Harvard University, her law degree from Yale Law School, and her doctorate in history and social study of science and technology from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

FILE - UW-Madison Chancellor Jennifer Mnookin during an interview at Vilas Hall in Madison, Wis., Aug. 4, 2022. (Amber Arnold/Wisconsin State Journal via AP, File)

From family-run cafes to retail giants, businesses are increasingly coming into the crosshairs of President Donald Trump’s mass deportation campaign, whether it's public pressure for them to speak out against aggressive immigration enforcement or becoming the sites for such arrests themselves.

In Minneapolis, where the Department of Homeland Security says it’s carrying out its largest operation ever, hotels, restaurants and other businesses have temporarily closed their doors or stopped accepting reservations amid widespread protests.

On Sunday, after the U.S. Border Patrol shot and killed Alex Pretti in Minneapolis, more than 60 CEOs of Minnesota-based companies including Target, Best Buy and UnitedHealth signed an open letter calling for "an immediate deescalation of tensions and for state, local and federal officials to work together to find real solutions.”

Still, that letter didn’t name immigration enforcement directly, or point to recent arrests at businesses. Earlier this month, widely-circulated videos showed federal agents detaining two Target employees in Minnesota. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has also rounded up day laborers in Home Depot parking lots and delivery workers on the street nationwide. And last year, federal agents detained 475 people during a raid at a Hyundai plant in Georgia.

Here's what we know about immigration enforcement in businesses.

Anyone — including ICE — can enter public areas of a business as they wish. This can include restaurant dining sections, open parking lots, office lobbies and shopping aisles.

“The general public can go into a store for purposes of shopping, right? And so can law enforcement agents — without a warrant,” said Jessie Hahn, senior counsel for labor and employment policy at the National Immigration Law Center, an advocacy nonprofit. As a result, immigration officials may try to question people, seize information and even make arrests in public-facing parts of a business.

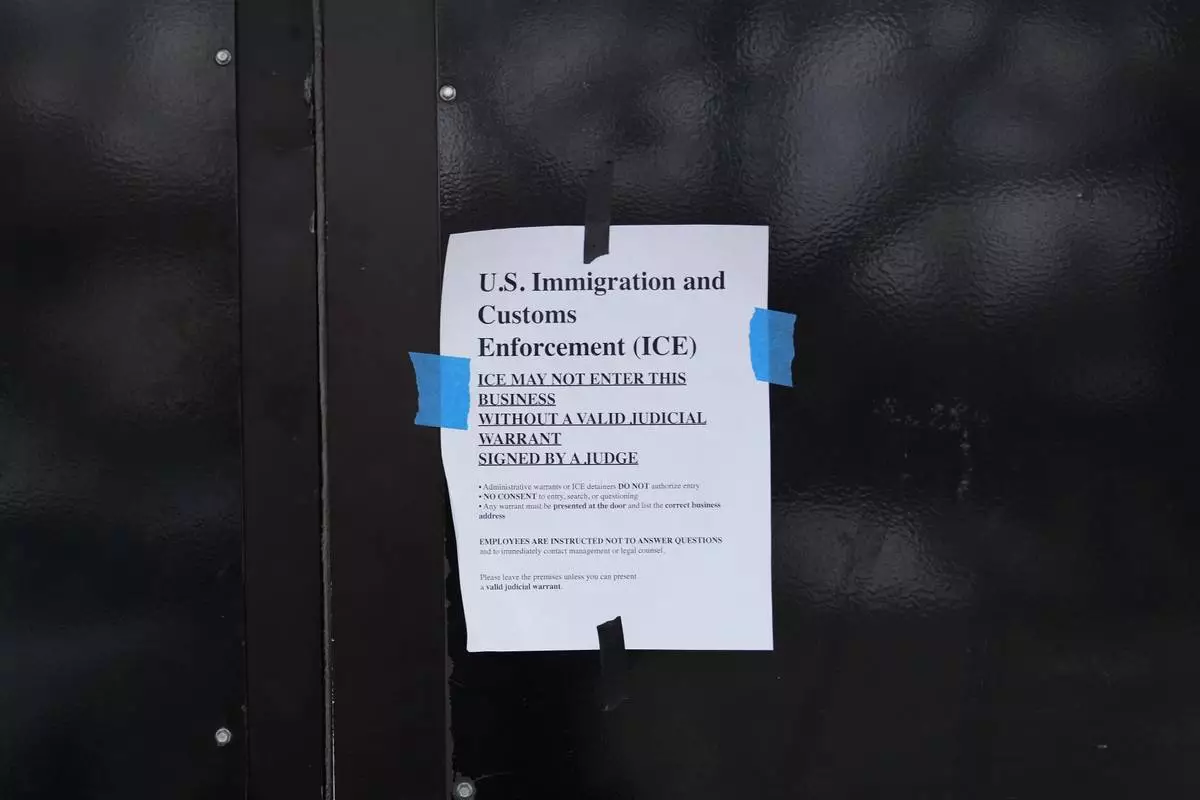

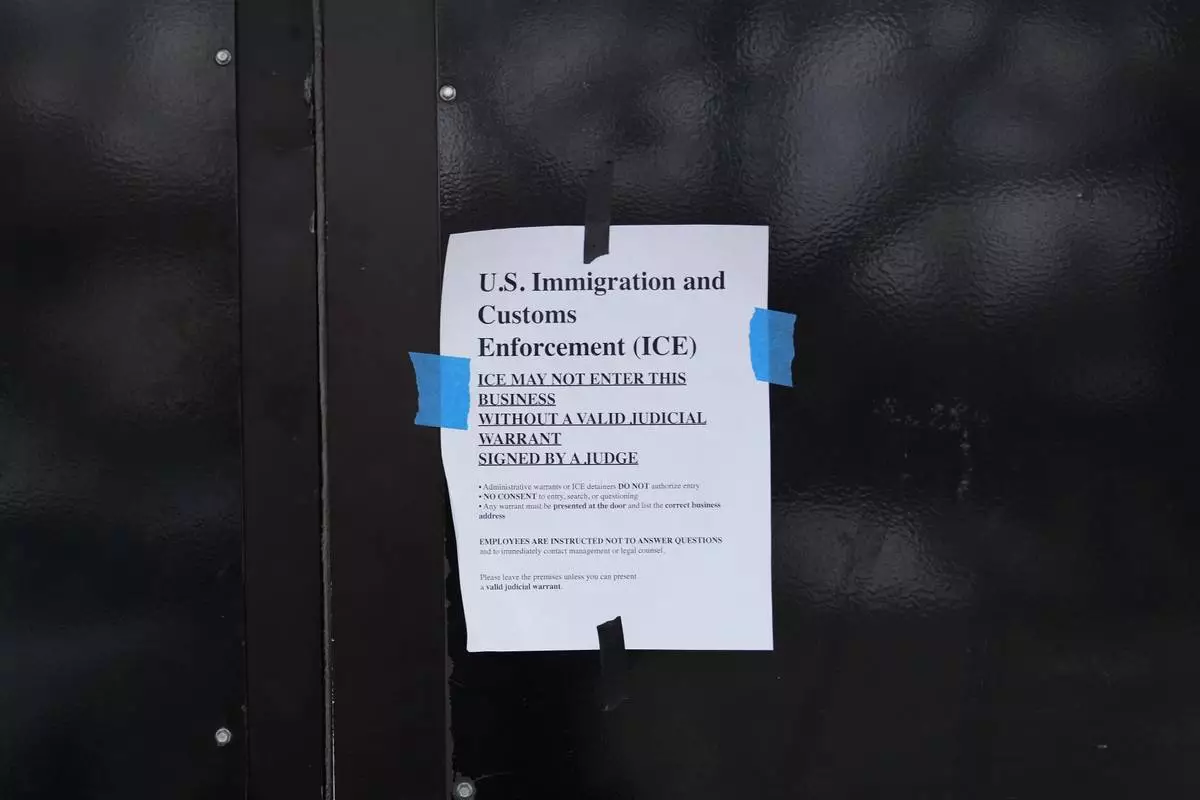

But to enter areas where there's a reasonable expectation of privacy — like a back office or a closed-off kitchen — ICE is supposed to have a judicial warrant, which must be signed by a judge from a specified court, and can be limited to specific days or parts of the business.

Judicial warrants should not be confused with administrative warrants, which are signed by immigration officers.

But in an internal memo obtained by The Associated Press, ICE leadership stated administrative warrants were sufficient for federal officers to forcibly enter people's homes if there’s a final order of removal. Hahn and other immigration rights lawyers say this upends years of precedent for federal agents’ authority in private spaces — and violates “bedrock principles” of the U.S. Constitution.

Still, the easiest way for ICE to enter private spaces in businesses without a warrant is through consent from an employer. That could be as simple as someone agreeing to let an agent into certain parts of the property. The agency may also cite other “exigent circumstances,” Hahn notes, such as if they’re in “hot pursuit” of a certain individual.

Beyond more sweeping workplace raids, enforcement against employers can also take the form of I-9 audits, which focus on verifying employees' authorization to work in the U.S.

Since the start of Trump’s second term, attorneys have pointed to an uptick in instances of ICE physically showing up to a place of business to initiate an I-9 audit. ICE has the authority to do this — but it marks a shift from prior enforcement, when I-9 audits more often began through writing like mailed notices.

David Jones, a regional managing partner at labor and employment law firm Fisher Phillips in Memphis, said he's also seen immigration agents approach these audits with the same approach as recent raids.

“ICE is still showing up in their full tactical gear without identifying themselves necessarily, just to do things like serve a notice of inspection,” Jones said. Employers have three days to respond to an I-9 audit, but he and others note that agents behaving aggressively might make some businesses think they need to act more immediately.

If ICE shows up without a warrant, businesses can ask agents to leave — or potentially refuse service based on their own company policy, perhaps citing safety concerns or other disruptions caused by agents' presence. But there's no guarantee immigration officials will comply, especially in public spaces.

“That’s not what we’re seeing here in Minnesota. What we’re seeing is they still conduct the activity,” said John Medeiros, who leads corporate immigration practice at Minneapolis-based law firm Nilan Johnson Lewis.

Because of this, Medeiros said, the question for many businesses becomes less about getting ICE to leave their property and more about what to do if ICE violates consent and other legal requirements.

In Minneapolis — and other cities that have seen surges in immigration enforcement, including Chicago and Los Angeles — some businesses have put up signs to label private spaces, educated workers on how to read different warrants and set wider protocols for what to do when ICE arrives.

Vanessa Matsis-McCready, associate general counsel and vice president of HR at Engage PEO, says she's also seen a nationwide uptick in interest for I-9 self-audits across sectors and additional emergency preparation.

ICE's increased presence and forceful arrests at businesses has sparked public outcry, some of it directed at the companies themselves for not taking a strong enough stand.

Some employers, particularly smaller business owners, are speaking out about ICE's impacts on their workers and customers. But a handful of bigger corporations have stayed largely silent, at least publicly, about enforcement making its way to their storefronts.

Minneapolis-based Target, for example, has not commented on videos of federal agents detaining two of its employees earlier this month, although its incoming chief executive, Michael Fiddelke, was one of the 60 CEOs who signed the Minnesota Chamber of Commerce's letter calling for broader de-escalation. The letter also got support of the Business Roundtable, a lobbying group of CEOs from more than 200 companies.

Target is among companies that organizers with “ICE Out of Minnesota” have asked to take strong public stances over ICE's presence in the state. Others include Home Depot, whose parking lots have become a known site of ICE raids over the last year, and Hilton — which protestors said was among brands of Twin City-area hotels that have housed federal agents.

Hilton and Home Depot did not respond to comment requests over the activists' calls. Home Depot previously denied being involved in immigration operations.

Several worker groups have been more outspoken. Ted Pappageorge, secretary-treasurer for a local chapter of the Culinary Union in Las Vegas, said members have been shocked by a “widening pattern of unlawful ICE behavior” nationwide and “recognize that anti-immigrant policies hurt tourism, business, and their families.” United Auto Workers also expressed solidarity with Minneapolis residents "fighting back against the federal government’s abuses and attacks on the working class.”

Hahn of the National Immigration Law Center noted some businesses are communicating through industry associations to avoid direct exposure to possible retaliation. Still, she stressed the importance of speaking publicly about the impacts of immigration enforcement overall.

“We know that the raids are contributing to things like labor shortages and reduced foot traffic,” Hahn said, adding that fears to push back on “this abuse of power from Trump could ultimately land us in a very different looking economy.”

Associated Press Writer Rio Yamat in Las Vegas and Anne D'Innocenzio in New York contributed to this report.

FILE - A sign is taped to the outside of the 24 Somali Mall in Minneapolis, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Abbie Parr, File)

FILE - U.S. Border Patrol Cmdr. Gregory Bovino walks through a Target store Jan. 11, 2026, in St. Paul, Minn. (AP Photo/Adam Gray, File)