RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — When Lourdes Barreto fled her home in Brazil’s northeastern state of Paraiba as a teenager — a move that launched her into sex work and a lifetime of activism — she never imagined that a samba school in Rio de Janeiro would pay tribute to her life's journey six decades later.

That’s exactly what Porto da Pedra will do this weekend at Rio’s famed Sambodrome as annual Carnival celebrations kick off. The samba school based in the low-income city of Sao Goncalo — across the bay from Rio — will celebrate Barreto and sex workers of all genders in an effort to dismantle the stigma surrounding the profession.

Click to Gallery

Pole dancer Sara Santos, center, prepares for a media presentation at the Porto da Pedra samba school in Sao Goncalo, Rio de Janeiro state, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

A sex worker dances during a pre-Carnival street party in the Vila Mimosa red-light district in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

Former sex worker Lourdes Barreto shows a tattoo that reads in Portuguese, "I am a whore," at the Porta da Pedra samba school in Rio de Janeiro, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

Members of Porto da Pedra samba school, which this year is raising awareness for sex workers to dismantle stigma, dance during a rehearsal ahead of the Carnival parade, in Sao Goncalo, Rio de Janeiro state, Thursday, Feb. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

Former sex worker Lourdes Barreto dances during Porto da Pedra samba school's rehearsal for a parade, spotlighting sex workers to dismantle stigma, ahead of a Carnival parade in Sao Goncalo, Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil, Wednesday, Feb. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

“Who would have thought that a prostitute would be honored?” the 83-year-old Barreto asked during a video call from her home in Belem, before a trip to Rio for the parade.

Samba is an energetic Brazilian music and dance genre that developed in Afro-Brazilian communities. Schools spend months preparing a parade with a song, elaborate floats and costumes, which they then present to judges at the joyful, but fierce, competition during Carnival.

Porto da Pedra creative director Mauro Quintaes, who designed this year’s theme for the school, previously curated two parades centered on populations living on the margins: thieves and people with severe mental health issues.

This year’s parade, titled “From life’s oldest times, the sweet and bitter kiss of the night,” serves as the final chapter in a trilogy Quintaes envisioned at the beginning of his career.

“The school is trying to make these women more seen, less invisible,” Quintaes said. “It’s not an apology nor a glamorization.”

Sex work isn't a crime in Brazil when performed voluntarily by adults. Since 2002, prostitution has been recognized as an official occupation by Brazil’s labor ministry, allowing sex workers to access social security and other work benefits.

However, the Global Network of Sex Work Projects says that police still target sex workers and carry out evictions.

This is largely because neither prostitution nor sexual exploitation — the latter of which is a crime — is explicitly defined in the law. According to a 2017 report by the nonprofit group Davida, these legal gaps grant police discretionary power to regulate sex work arbitrarily.

Barreto co-founded the Brazilian Network of Prostitutes in the 1980s to fight for better rights for sex workers in Brazil. She stood up to the military police, campaigned to establish HIV prevention policies and even ran for a seat as a councilwoman.

In 2024, the BBC listed her as one of 100 inspiring and influential women from around the world, alongside fellow countrywoman Olympic athlete Rebeca Andrade, French rape survivor Gisèle Pelicot and Nigerian climate campaigner Adenike Oladosu.

“I’ve always seen myself as a working woman. Not sinning, not doing anything wrong,” she said.

While sex work has already been evoked in previous parades, Porto da Pedra’s approach is groundbreaking for its central focus and emphasis on class struggle, said Juliana Barbosa, a communications professor at the Federal University of Parana and a Carnival expert.

Barbosa said that samba schools, which emerged from Black communities, have a history of seizing on social issues to force a conversation.

“The theme stays for months within those communities, being sung about and discussed, and then it spreads to a very large number of people,” Barbosa said. “It can contribute to social change. Not as a rule, not on all subjects, but it has that tendency.”

Andrea de Andrade, 39, will lead Porta da Pedra’s percussion section in the prestigious role of drum queen. Now a prominent social media figure, she recalls how Carnival themes from 20 years ago introduced her to issues and stories she had never heard about before.

“Many people don’t have access to much, not just due to a lack of funds, but also a lack of time. Many don’t read, don’t study — but Brazilians love Carnival,” she said.

More than 50 sex workers of all genders from all corners of Brazil are expected to march Saturday evening alongside hundreds of others.

Thauany Laressa, a 27-year-old sex worker from Brazil’s northern state of Rondonia, reached out to the school after finding out about this year's theme. For too long, sex work has been taboo, she said.

“I hope that people who see the parade will have more compassion when interacting with sex workers and help them accept it as a profession,” Laressa said. “I hope that people will start respecting our lives, our way of life and our job.”

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

Pole dancer Sara Santos, center, prepares for a media presentation at the Porto da Pedra samba school in Sao Goncalo, Rio de Janeiro state, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

A sex worker dances during a pre-Carnival street party in the Vila Mimosa red-light district in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

Former sex worker Lourdes Barreto shows a tattoo that reads in Portuguese, "I am a whore," at the Porta da Pedra samba school in Rio de Janeiro, Monday, Feb. 9, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

Members of Porto da Pedra samba school, which this year is raising awareness for sex workers to dismantle stigma, dance during a rehearsal ahead of the Carnival parade, in Sao Goncalo, Rio de Janeiro state, Thursday, Feb. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

Former sex worker Lourdes Barreto dances during Porto da Pedra samba school's rehearsal for a parade, spotlighting sex workers to dismantle stigma, ahead of a Carnival parade in Sao Goncalo, Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil, Wednesday, Feb. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo)

HARRISBURG, Pa. (AP) — As outrage spreads over energy-hungry data centers, politicians from President Donald Trump to local lawmakers have found rare bipartisan agreement over insisting that tech companies — and not regular people — must foot the bill for the exorbitant amount of electricity required for artificial intelligence.

But that might be where the agreement ends.

The price of powering data centers has become deeply intertwined with concerns over the cost of living, a dominant issue in the upcoming midterm elections that will determine control of Congress and governors’ offices.

Some efforts to address the challenge may be coming too late, with energy costs on the rise. And even though tech giants are pledging to pay their “fair share,” there's little consensus on what that means.

“‘Fair share’ is a pretty squishy term, and so it’s something that the industry likes to say because ‘fair’ can mean different things to different people,” said Ari Peskoe, who directs the Electricity Law Initiative at Harvard University.

It's a shift from last year, when states worked to woo massive data center projects and Trump directed his administration to do everything it could to get them electricity. Now there's a backlash as towns fight data center projects and some utilities' electricity bills have risen quickly.

Anger over the issue has already had electoral consequences, with Democrats ousting two Republicans from Georgia's utility regulatory commission in November.

“Voters are already connecting the experience of these facilities with their electricity costs and they’re going to increasingly want to know how government is going to navigate that,” said Christopher Borick, a pollster and director of the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion.

Data centers are sprouting across the U.S., as tech giants scramble to meet worldwide demand for chatbots and other generative AI products that require large amounts of computing power to train and operate.

The buildings look like giant warehouses, some dwarfing the footprints of factories and stadiums. Some need more power than a small city, more than any utility has ever supplied to a single user, setting off a race to build more power plants.

The demand for electricity can have a ripple effect that raises prices for everyone else. For example, if utilities build more power plants or transmission lines to serve them, the cost can be spread across all ratepayers.

Concerns have dovetailed with broader questions about the cost of living, as well as fears about the powerful influence of tech companies and the impact of artificial intelligence.

Trump continues to embrace artificial intelligence as a top economic and national security priority, although he seemed to acknowledge the backlash last month by posting on social media that data centers “must ‘pay their own way.’”

At other times, he has brushed concerns aside, declaring that tech giants are building their own power plants, and Energy Secretary Chris Wright contends that data centers don't inflate electricity bills — disputing what consumer advocates and independent analysts say.

Some states and utilities have started to identify ways to get data centers to pay for their costs.

They've required tech companies to buy electricity in long-term contracts, pay for the power plants and transmission upgrades they need and make big down payments in case they go belly-up or decide later they don’t need as much electricity.

But it might be more complicated than that. Those rules can't fix the short-term problem of ravenous demand for electricity that is outpacing the speed of power plant construction, analysts say.

“What do you do when Big Tech, because of the very profitable nature of these data centers, can simply outbid grandma for power in the short run?” Abe Silverman, a former utility regulatory lawyer and an energy researcher at Johns Hopkins University. “That is, I think, going to be the real challenge.”

Some consumer advocates say tech companies' fair share should also include the rising cost of electricity, grid equipment or natural gas that’s driven by their demand.

In Oregon, which passed a law to protect smaller ratepayers from data centers' power costs, a consumer advocacy group is jousting with the state's largest utility, Portland General Electric, over its plan on how to do that.

Meanwhile, consumer advocates in various states — including Indiana, Georgia and Missouri — are warning that utilities could foist the cost of data center-driven buildouts onto regular ratepayers there.

Utilities have pledged to ensure electric rates are fair. But in some places it may be too late.

For instance, in the mid-Atlantic grid territory from New Jersey to Illinois, consumer advocates and analysts have pegged billions of dollars in rate increases hitting the bills of regular Americans on data center demand.

Legislation, meanwhile, is flooding into Congress and statehouses to regulate data centers.

Democrats’ bills in Congress await Republican cosponsors, while lawmakers in a number of states are floating moratoriums on new data centers, drafting rules for regulators to shield regular ratepayers and targeting data center tax breaks and utility profits.

Governors — including some who worked to recruit data centers to their states — are increasingly talking tough.

Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs, a Democrat running for reelection this year, wants to impose a penny-a-gallon water fee on data centers and get rid of the sales tax exemption there that most states offer data centers. She called it a $38 million “corporate handout.”

“It’s time we make the booming data center industry work for the people of our state, rather than the other way around,” she said in her state-of-the-state address.

Energy costs are projected to keep rising in 2026.

Republicans in Washington are pointing the finger at liberal state energy policies that favor renewable energy, suggesting they have driven up transmission costs and frayed supply by blocking fossil fuels.

“Americans are not paying higher prices because of data centers. There’s a perception there, and I get the perception, but it’s not actually true,” said Wright, Trump's energy secretary, at a news conference earlier this month.

The struggle to assign blame was on display last week at a four-hour U.S. House subcommittee hearing with members of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

Republicans encouraged FERC members to speed up natural gas pipeline construction while Democrats defended renewable energy and urged FERC to limit utility profits and protect residential ratepayers from data center costs.

FERC's chair, Laura Swett, told Rep. Greg Landsman, D-Ohio, that she believes data center operators are willing to cover their costs and understand that it’s important to have community support.

“That’s not been our experience,” Landsman responded, saying projects in his district are getting tax breaks, sidestepping community opposition and costing people money. “Ultimately, I think we have to get to a place where they pay everything.”

Follow Marc Levy on X at: https://x.com/timelywriter

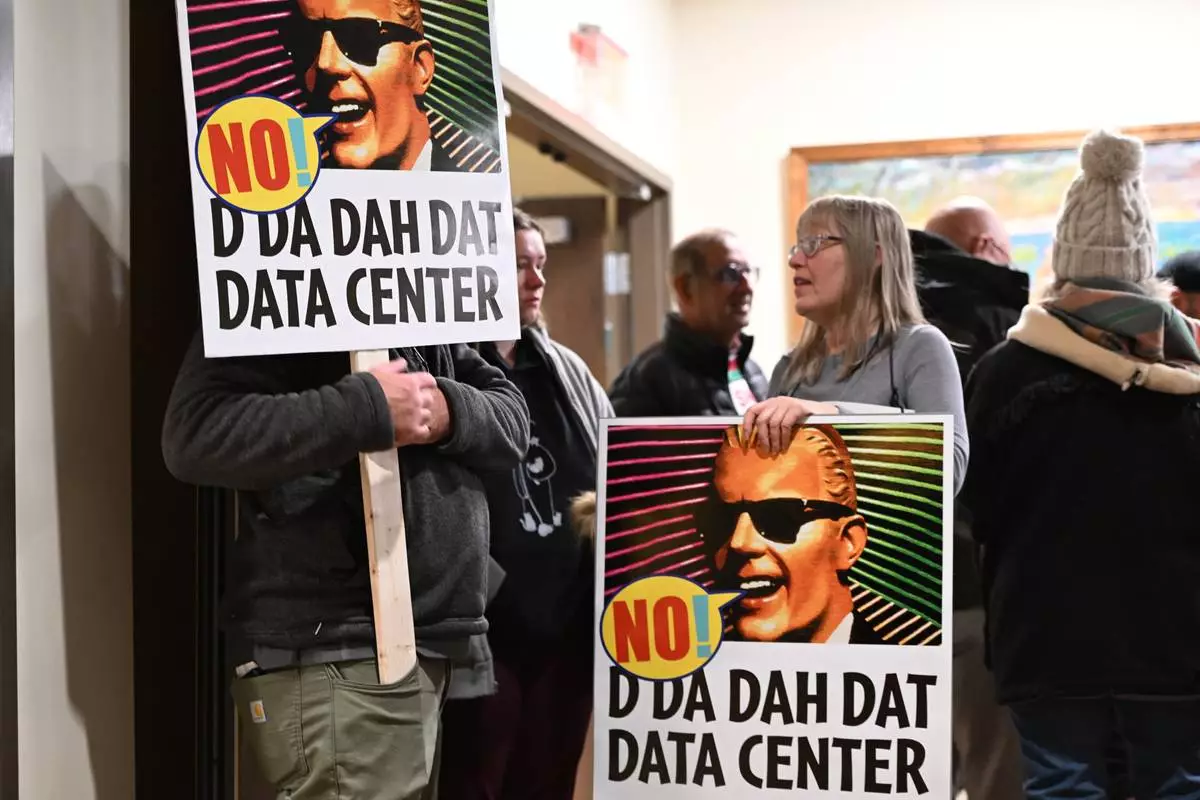

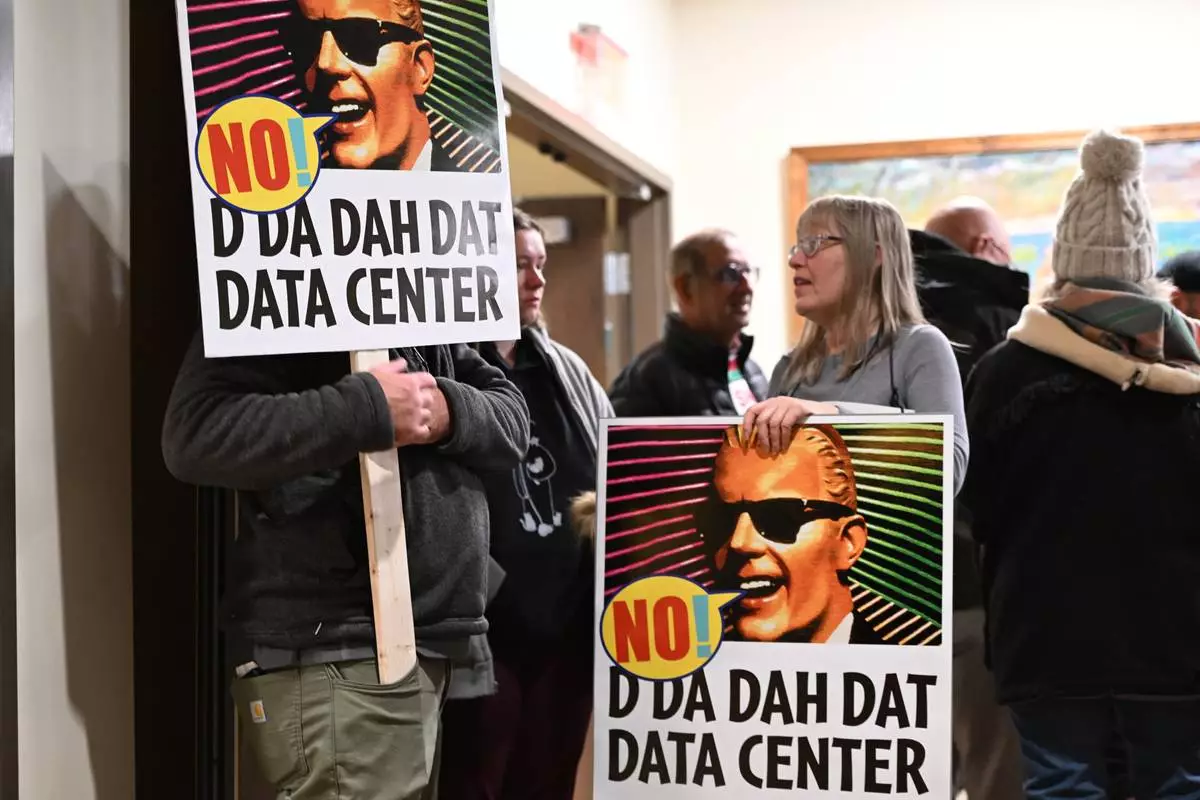

FILE - People opposed to a data center proposal at the former Pennhurst state hospital grounds talk during a break in an East Vincent Township supervisors meeting, Dec. 17, 2025, in Spring City, Pa. (AP Photo/Marc Levy, file)

FILE - High-voltage transmission lines provide electricity to data centers in Ashburn in Loudon County, Virginia, on July 16, 2023. (AP Photo/Ted Shaffrey, File)

FILE - A data center owned by Amazon Web Services, front right, is under construction next to the Susquehanna nuclear power plant in Berwick, Pa., Jan. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Ted Shaffrey, File)