BANGKOK (AP) — When Thai police were having trouble catching a serial burglar who repeatedly slipped through their fingers, they came up with a creative plan: going undercover in a traditional lion costume to get close to their elusive quarry.

Video footage released by the Bangkok police department showed officers hidden beneath a red-and-gold lion costume dancing toward the suspect on Wednesday as he wandered through a Lunar New Year fair at a temple in Nonthaburi, a province neighboring Bangkok. Moments later, the officer who was holding the lion’s papier-mache head lunges at the suspect swiftly pins the man to the ground.

Police say the suspect, identified as a 33-year-old man, is accused of breaking into the home of a local police commander in Bangkok three times earlier this month, making off with valuables worth about 2 million baht ($64,000).

In a press release, police said they had attempted to arrest the man several times, but he was quick to spot police officers and ran off. They later identified him by tracing stolen amulets he had sold and learned that he frequently visited temples in Nonthaburi.

While the Lunar New Year is not an official holiday in Thailand, celebrations are common and lion dances are often part of the festivities, providing the perfect cover for the operation.

Police said the suspect has confessed to the buglaries, saying he stole to buy drugs and gamble. They added that he has previously been convicted of drug-related offenses and burglary.

In this image released by Thailand’s Metropolitan Police Bureau, Thai police disguised as lion dance performers catch a burglary suspect at a temple fair in Nonthaburi province, Wednesday, Feb. 18, 2026. (The Metropolitan Police Bureau via AP)

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (AP) — Thousands of Black soldiers performed the backbreaking work of transforming rough-hewn wilderness in extreme weather swings during World War II to help build the first road link between Alaska and the Lower 48.

The work of the segregated Black soldiers is credited with bringing changes to military discrimination policies. The state of Alaska honored them by naming a bridge for them near the end point of the famed Alaska Highway.

Now, eight decades later, the aging bridge needs to be replaced. Instead of tearing it down, the state of Alaska intends to keep two of the bridge’s nine trestles in place as a refashioned memorial. The others will be given away.

The state of Alaska will replace the 1,885-foot (575-meter) bridge that spans the Gerstle River near Delta Junction, the end point of the Alaska Highway about 100 miles (161 kilometers) south of Fairbanks.

Seven of the bridge’s trestles are being offered for free to states, local governments or private entities who will maintain them for their historical features and public use.

The two remaining spans from the old bridge, renamed the Black Veterans Memorial Bridge in 1993, will honor the 4,000 or so Black soldiers who built the first wooden bridge over the river while completing the Alaska Highway.

These two sections, the first trestles on either end, will retain the name of the memorial bridge. The new Gerstle River Bridge will unofficially carry the memorial name unless the Legislature also makes it official. The old bridge will remain in place until the new one opens in 2031.

Mary Leith, a former Delta Junction mayor and member of the historical society, said she’s pleased some of the history will be saved, but she wants the state to have proper signage and a highway pullout area near the historic bridge to allow people to walk on it.

“I would hope that if they’re going to save it, then they save it properly,” she said.

The Black Veterans Memorial Bridge sign will remain and the two sections will be visible from the new bridge, but both will be blocked off to prevent people from climbing or vandalizing them, said Angelica Stabs, a spokesperson for the state transportation department. No pullout is planned.

The new bridge will parallel the existing bridge to the east, leaving about 50 feet of space between it and the old bridge's location, Stab said.

The project to build a supply route between Alaska and Canada used 11,000 troops from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers divided by race, working under a backdrop of segregation and discrimination. Besides transforming the rugged terrain, the soldiers had to deal with mosquitoes, boggy land, permafrost and temperatures ranging from 90 degrees F (32 degrees C) to minus 70 F (minus 56 C).

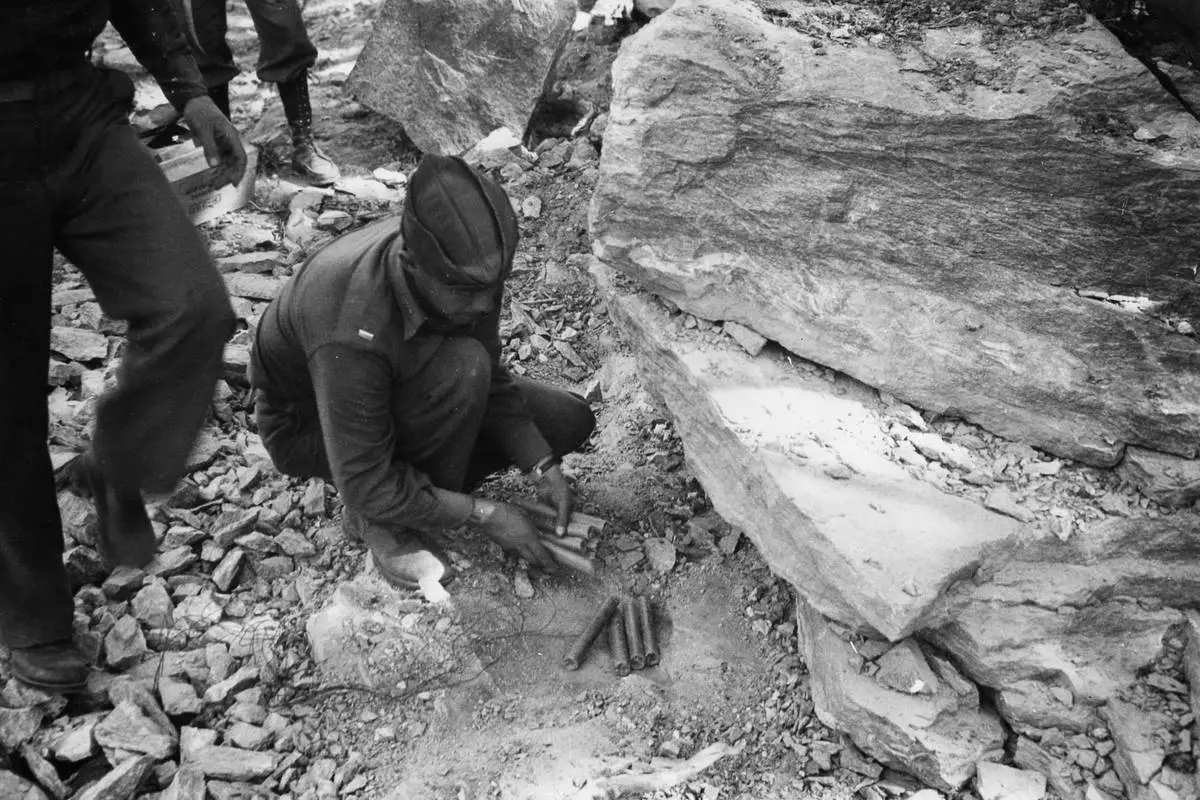

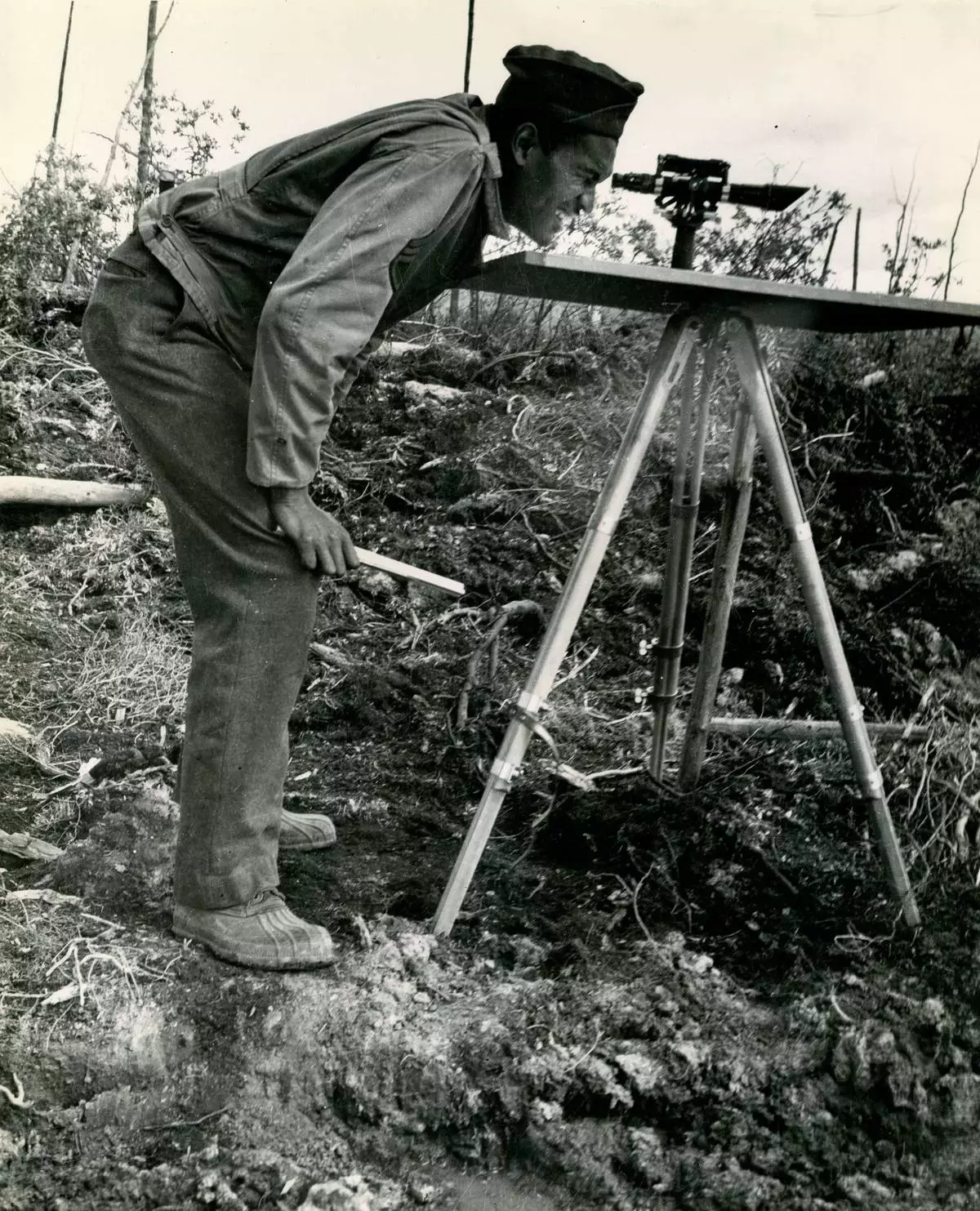

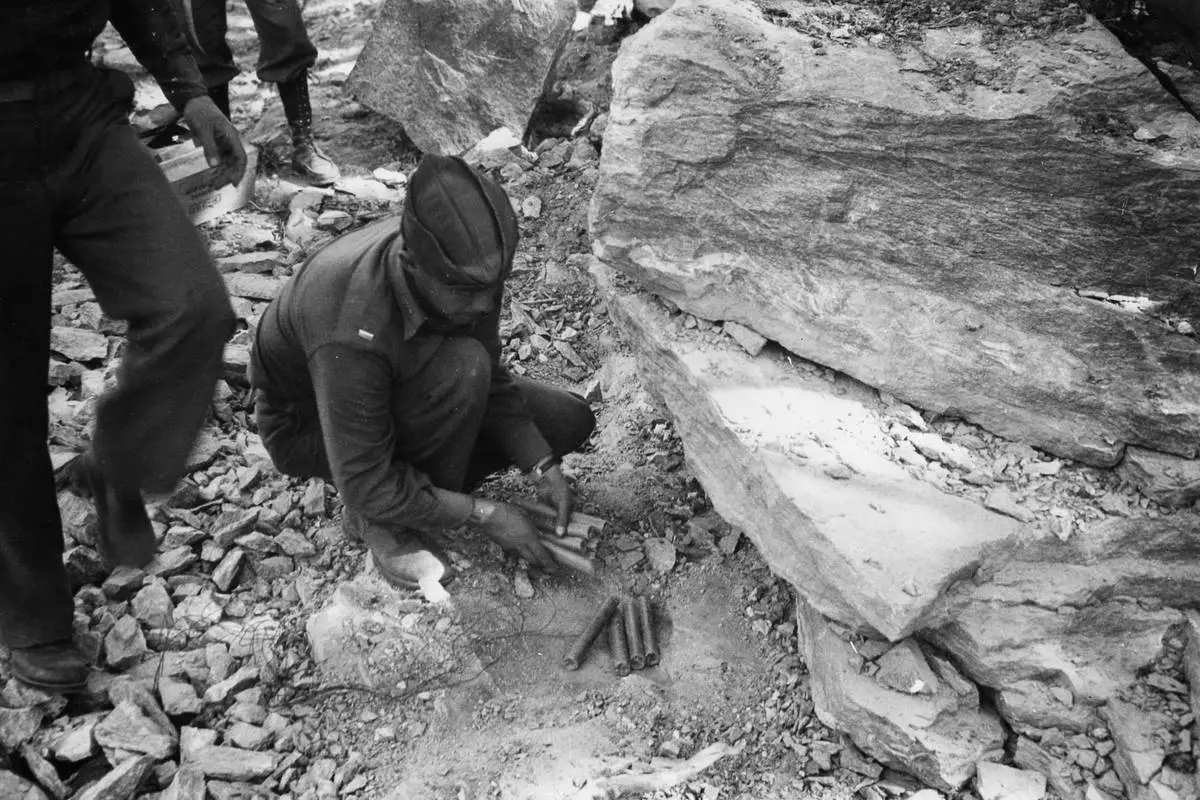

“Though conditions were harsh for all, they were nearly unbearable for black soldiers. From the Deep South, most of these soldiers had never encountered anything approaching the severe conditions of the far north. Moreover, since black troops were not typically permitted to use heavy machinery, they made do with picks, shovels, and axes. In addition, they were prohibited from entering towns and were confined to wilderness assignments,” according to a historical account by the National Park Service.

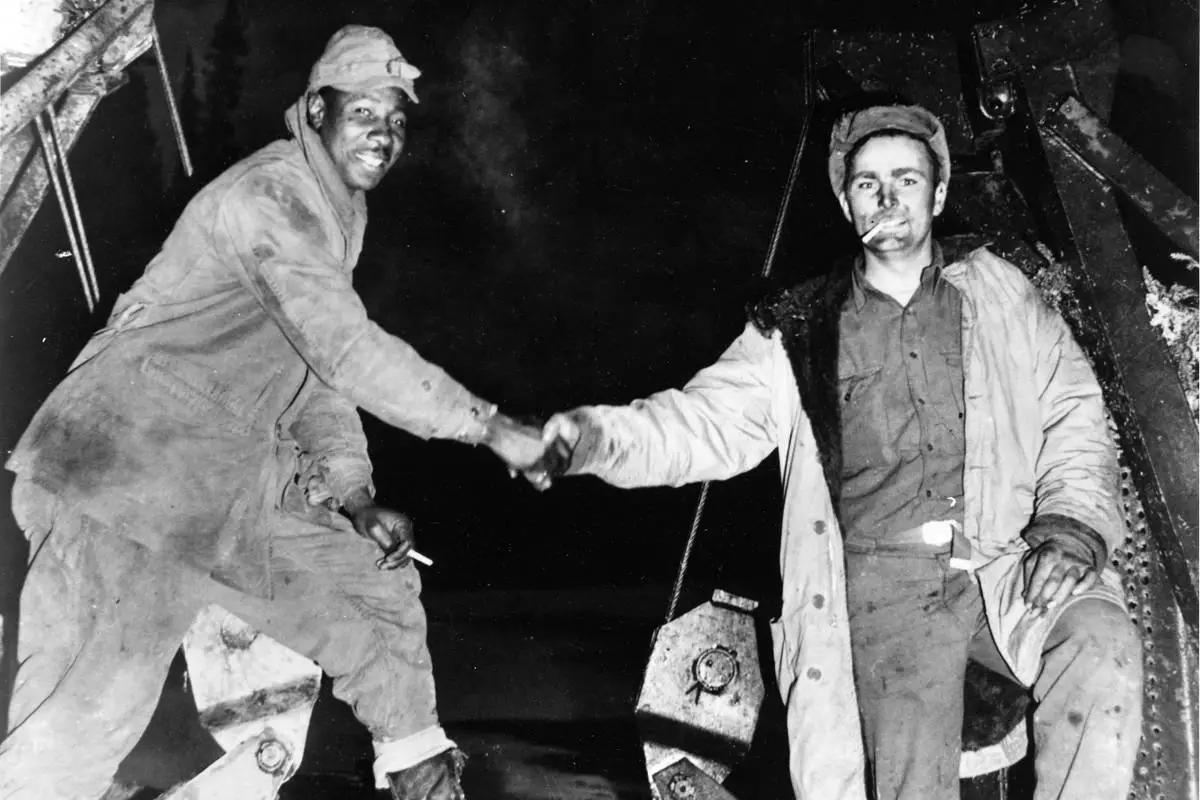

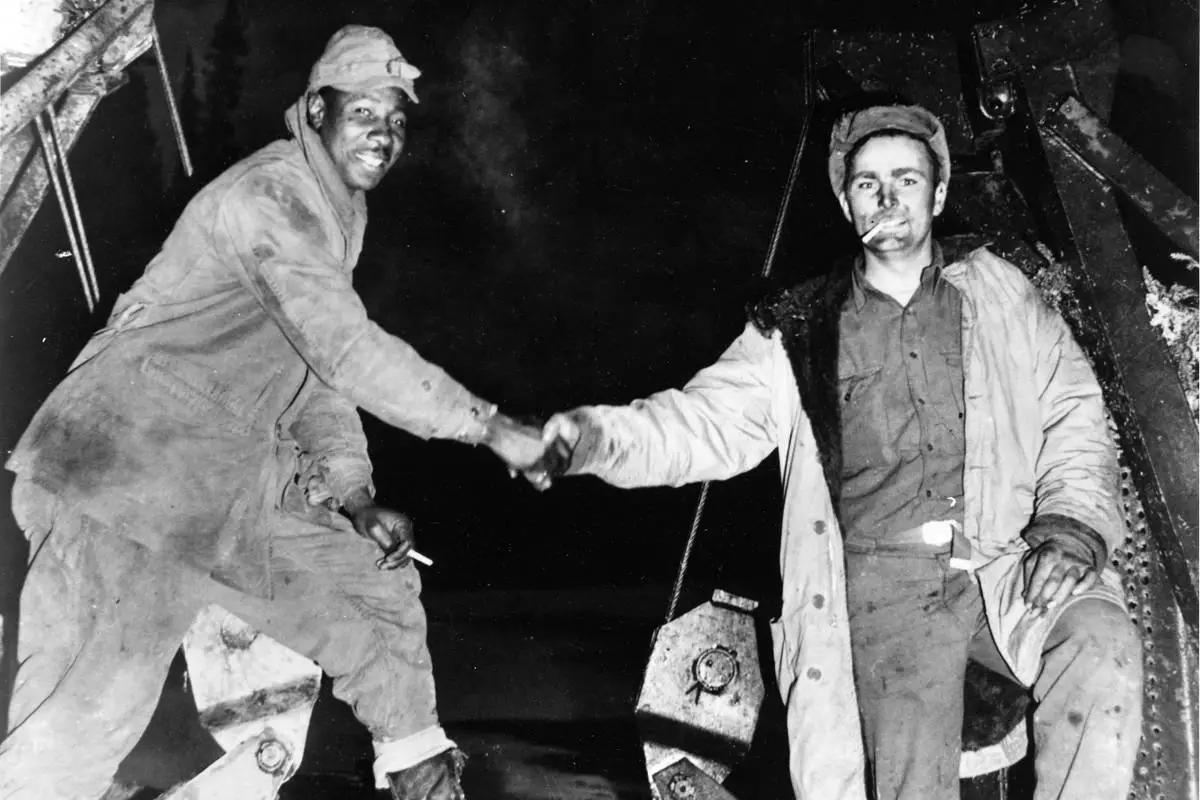

It took Black soldiers working from the north just over eight months to meet up with white soldiers coming from the south to connect the 1,500-mile (2,400-kilometer) gravel road, then called the Alcan Highway, from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Delta Junction Oct. 25, 1942.

“In light of their impressive performance, many of the black soldiers who worked on the Alcan were subsequently decorated and sometimes deployed in combat. Indeed, the U.S. Army eventually became the first government agency to integrate in 1948, a move that is largely credited in part to the laudable work of the soldiers who built the Alcan,” the National Park Service says.

Alaska was still a territory, and officials long wanted such a road to the Lower 48. However, battles over routes and its necessity led to delays.

Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and Dutch Harbor in Alaska, along with the Japanese invasions of the Alaska islands Kiska and Attu signaled urgency for the road since the ocean shipping lanes to the West Coast could be vulnerable.

Black soldiers working near Delta Junction built a temporary bridge over the Gerstle River in 1942. Contractors finished the steel structure two years later.

The Alaska transportation department is accepting proposals until March 6 for the seven trestles, but you don't have to take them all. The state will consider all proposals, even those seeking one or two trestles for uses such as a walkway over a creek in a public park.

Winners will have to abide by certain restrictions including not allowing vehicular traffic, paying for removal, transportation and lead abatement, and maintaining the features that make the bridge historically significant.

FILE - In this 1942 photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, a Black soldier places dynamite during construction of the Alaska Highway in the Northern Sector of Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

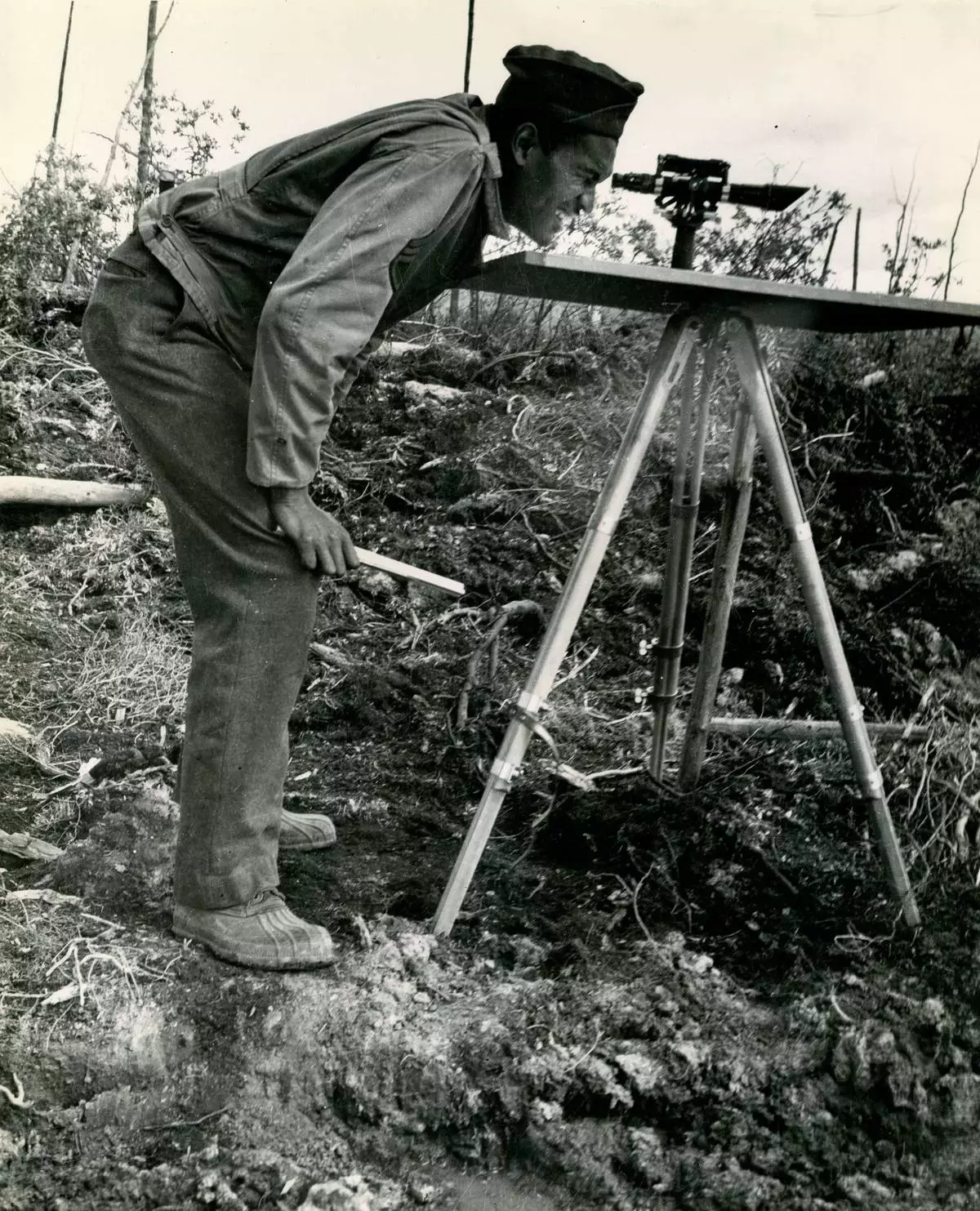

FILE - In this 1942 photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, a Black soldier peers through a surveyor's transit during construction of the Alaska Highway in the Northern Sector of Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

This undated photo provided by the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities shows a trestle bridge, that the state of Alaska is planning to replace, spanning the Gerstle River about 30 miles southeast of Delta Junction. (Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities via AP)

FILE - This Oct. 25, 1942, photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, shows Corporal Refines Slims, Jr., left, and Private Alfred Jalufka shaking hands at the, "Meeting of Bulldozers," for the ALCAN Highway in the Yukon Territory in Beaver Creek, Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)