ANCHORAGE, Alaska (AP) — Thousands of Black soldiers performed the backbreaking work of transforming rough-hewn wilderness in extreme weather swings during World War II to help build the first road link between Alaska and the Lower 48.

The work of the segregated Black soldiers is credited with bringing changes to military discrimination policies. The state of Alaska honored them by naming a bridge for them near the end point of the famed Alaska Highway.

Click to Gallery

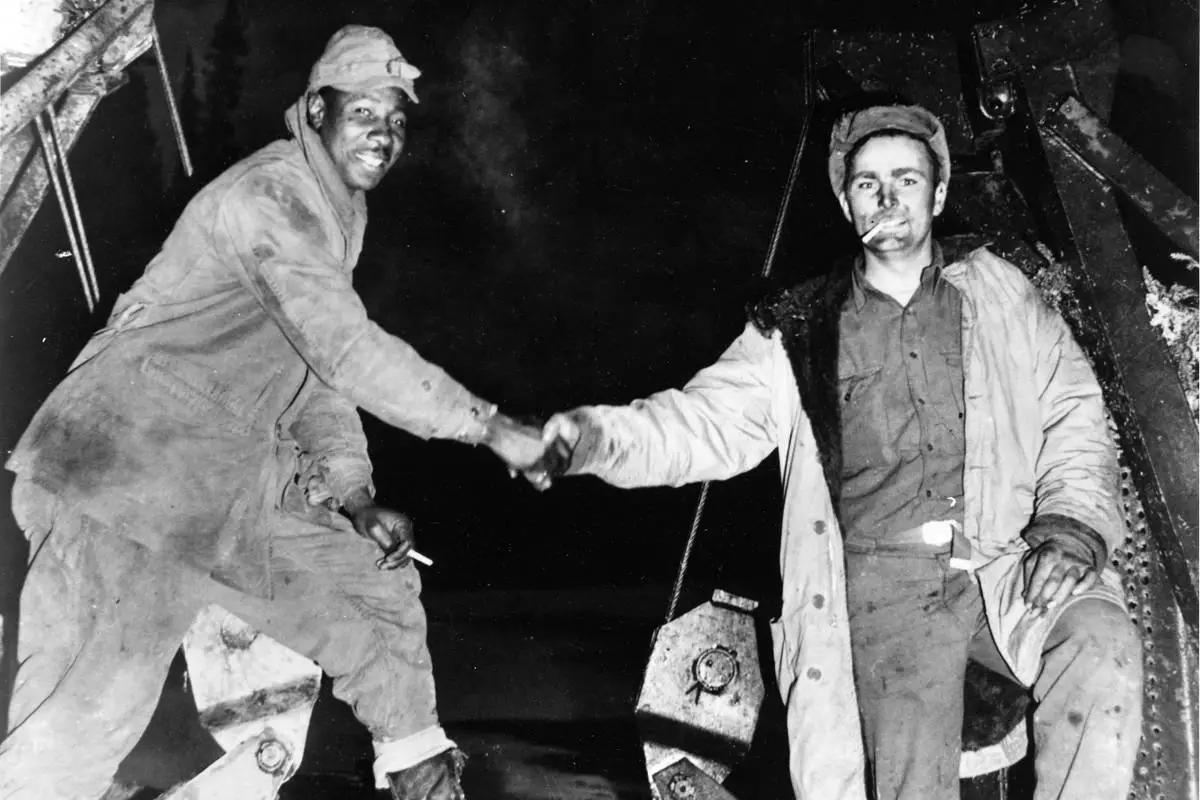

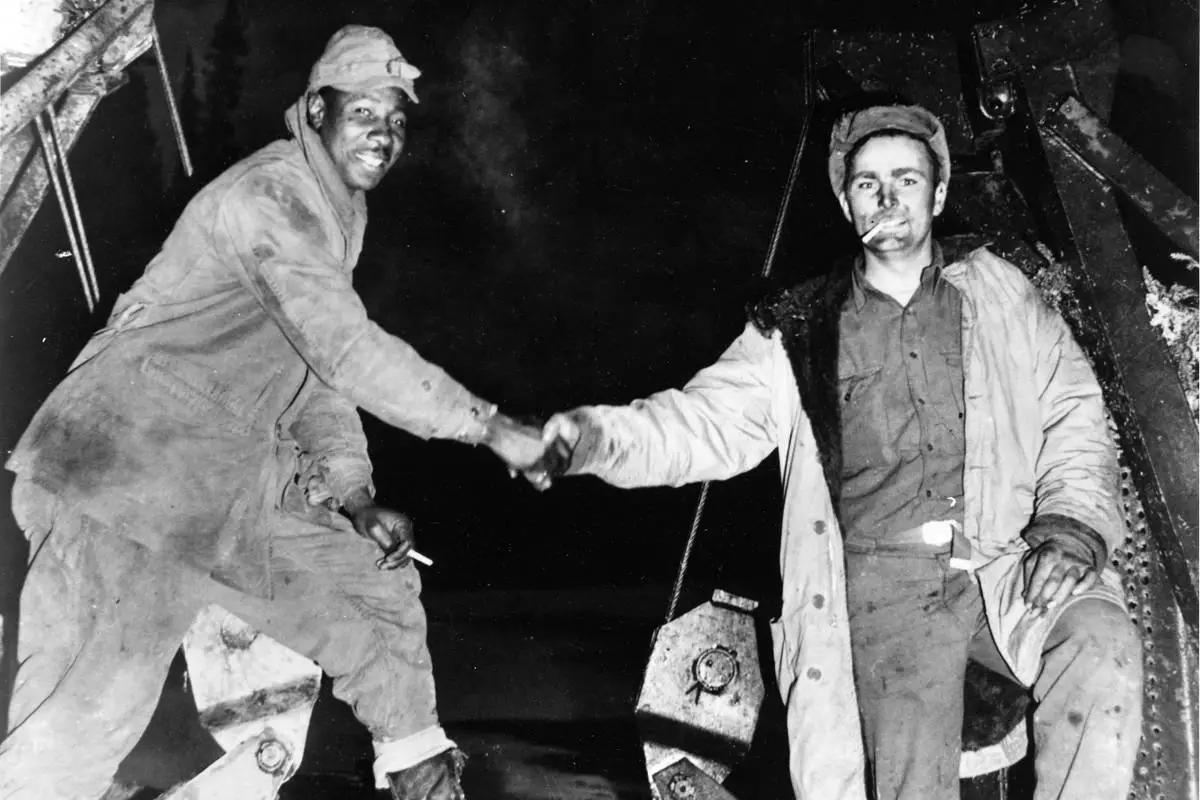

FILE - This Oct. 25, 1942, photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, shows Corporal Refines Slims, Jr., left, and Private Alfred Jalufka shaking hands at the, "Meeting of Bulldozers," for the ALCAN Highway in the Yukon Territory in Beaver Creek, Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

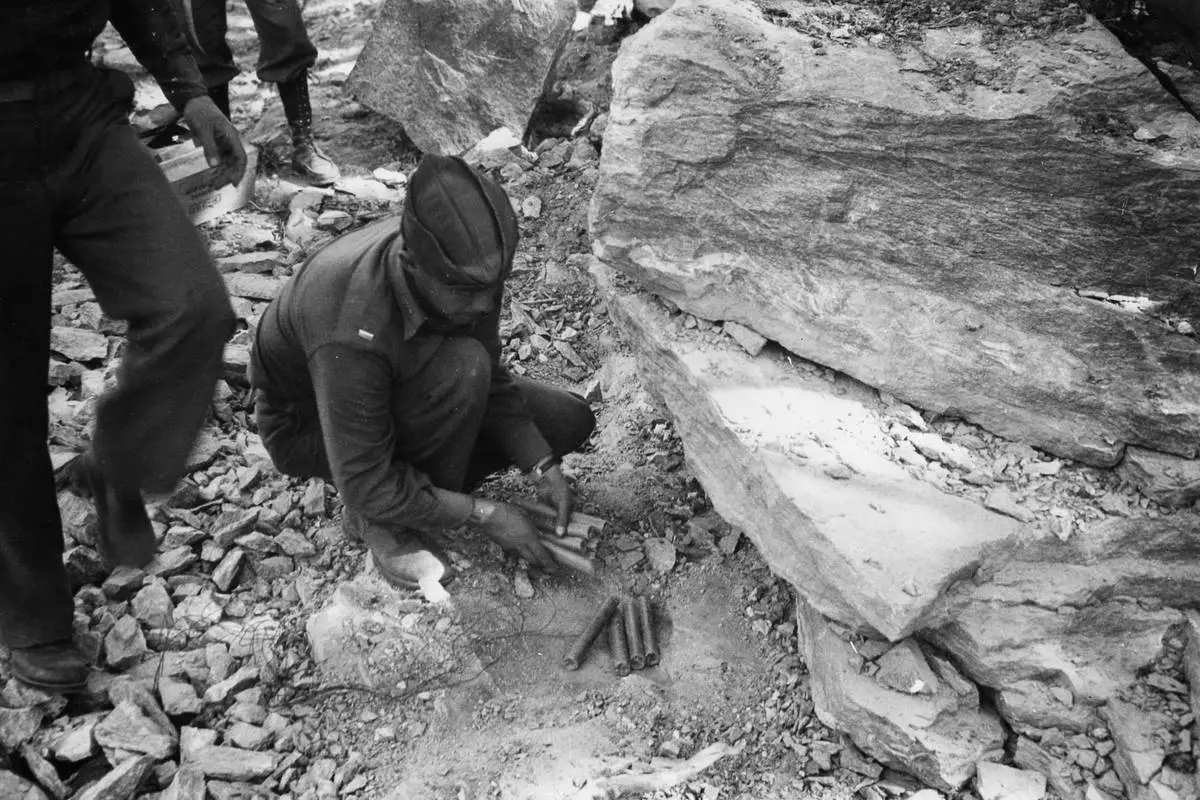

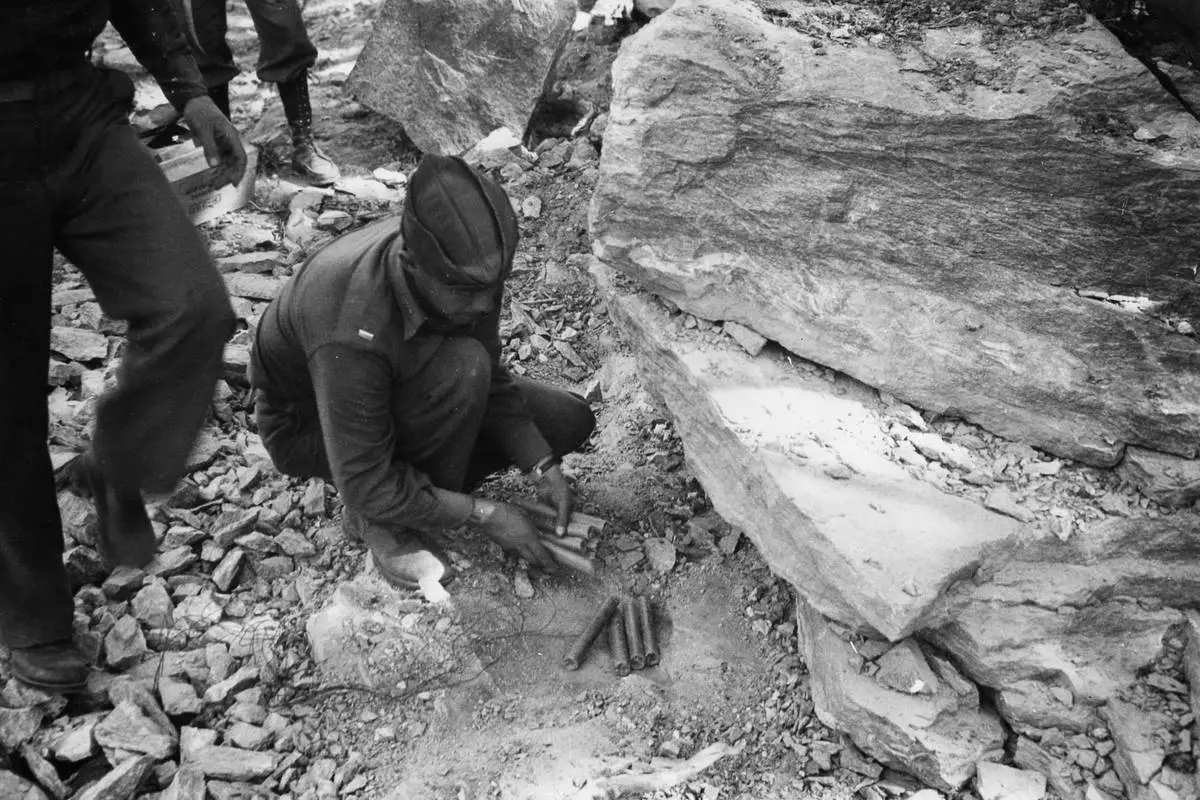

FILE - In this 1942 photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, a Black soldier places dynamite during construction of the Alaska Highway in the Northern Sector of Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

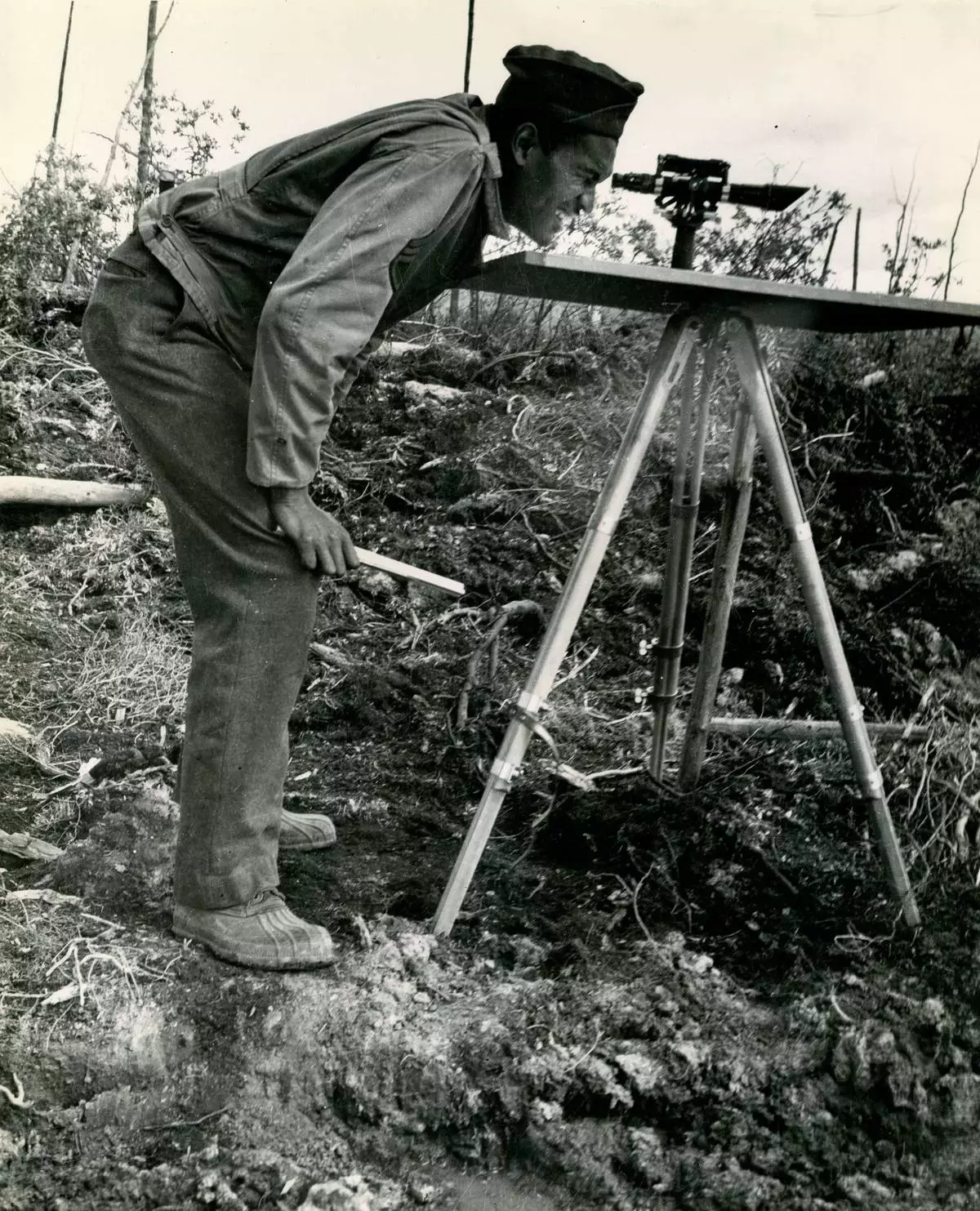

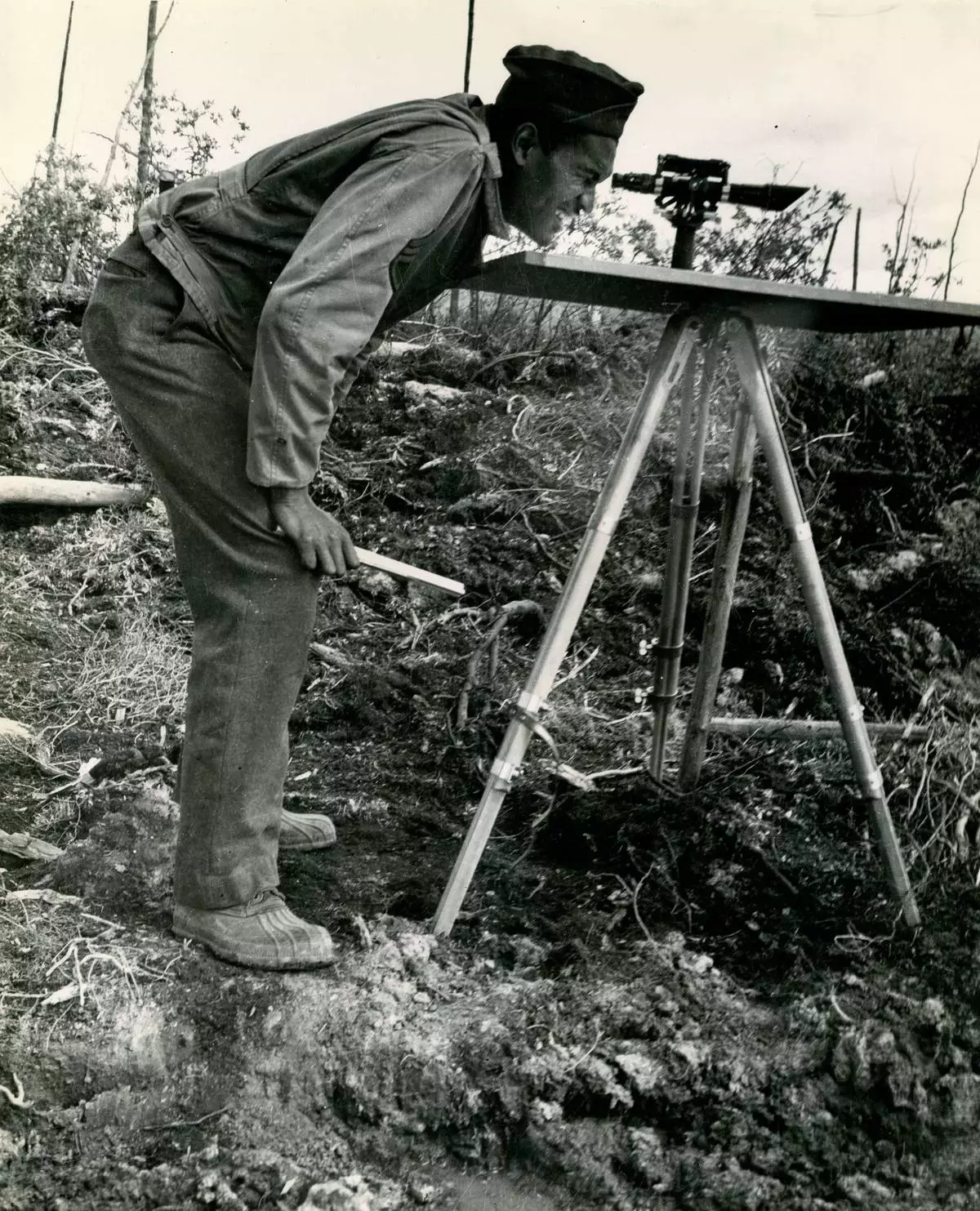

FILE - In this 1942 photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, a Black soldier peers through a surveyor's transit during construction of the Alaska Highway in the Northern Sector of Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

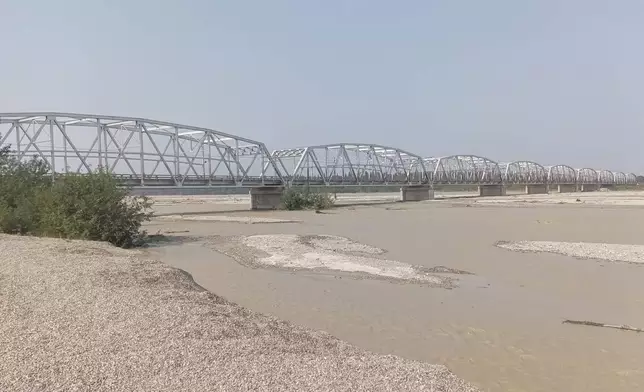

This undated photo provided by the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities shows a trestle bridge, that the state of Alaska is planning to replace, spanning the Gerstle River about 30 miles southeast of Delta Junction. (Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities via AP)

FILE - This Oct. 25, 1942, photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, shows Corporal Refines Slims, Jr., left, and Private Alfred Jalufka shaking hands at the, "Meeting of Bulldozers," for the ALCAN Highway in the Yukon Territory in Beaver Creek, Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

Now, eight decades later, the aging bridge needs to be replaced. Instead of tearing it down, the state of Alaska intends to keep two of the bridge’s nine trestles in place as a refashioned memorial. The others will be given away.

The state of Alaska will replace the 1,885-foot (575-meter) bridge that spans the Gerstle River near Delta Junction, the end point of the Alaska Highway about 100 miles (161 kilometers) south of Fairbanks.

Seven of the bridge’s trestles are being offered for free to states, local governments or private entities who will maintain them for their historical features and public use.

The two remaining spans from the old bridge, renamed the Black Veterans Memorial Bridge in 1993, will honor the 4,000 or so Black soldiers who built the first wooden bridge over the river while completing the Alaska Highway.

These two sections, the first trestles on either end, will retain the name of the memorial bridge. The new Gerstle River Bridge will unofficially carry the memorial name unless the Legislature also makes it official. The old bridge will remain in place until the new one opens in 2031.

Mary Leith, a former Delta Junction mayor and member of the historical society, said she’s pleased some of the history will be saved, but she wants the state to have proper signage and a highway pullout area near the historic bridge to allow people to walk on it.

“I would hope that if they’re going to save it, then they save it properly,” she said.

The Black Veterans Memorial Bridge sign will remain and the two sections will be visible from the new bridge, but both will be blocked off to prevent people from climbing or vandalizing them, said Angelica Stabs, a spokesperson for the state transportation department. No pullout is planned.

The new bridge will parallel the existing bridge to the east, leaving about 50 feet of space between it and the old bridge's location, Stab said.

The project to build a supply route between Alaska and Canada used 11,000 troops from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers divided by race, working under a backdrop of segregation and discrimination. Besides transforming the rugged terrain, the soldiers had to deal with mosquitoes, boggy land, permafrost and temperatures ranging from 90 degrees F (32 degrees C) to minus 70 F (minus 56 C).

“Though conditions were harsh for all, they were nearly unbearable for black soldiers. From the Deep South, most of these soldiers had never encountered anything approaching the severe conditions of the far north. Moreover, since black troops were not typically permitted to use heavy machinery, they made do with picks, shovels, and axes. In addition, they were prohibited from entering towns and were confined to wilderness assignments,” according to a historical account by the National Park Service.

It took Black soldiers working from the north just over eight months to meet up with white soldiers coming from the south to connect the 1,500-mile (2,400-kilometer) gravel road, then called the Alcan Highway, from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Delta Junction Oct. 25, 1942.

“In light of their impressive performance, many of the black soldiers who worked on the Alcan were subsequently decorated and sometimes deployed in combat. Indeed, the U.S. Army eventually became the first government agency to integrate in 1948, a move that is largely credited in part to the laudable work of the soldiers who built the Alcan,” the National Park Service says.

Alaska was still a territory, and officials long wanted such a road to the Lower 48. However, battles over routes and its necessity led to delays.

Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and Dutch Harbor in Alaska, along with the Japanese invasions of the Alaska islands Kiska and Attu signaled urgency for the road since the ocean shipping lanes to the West Coast could be vulnerable.

Black soldiers working near Delta Junction built a temporary bridge over the Gerstle River in 1942. Contractors finished the steel structure two years later.

The Alaska transportation department is accepting proposals until March 6 for the seven trestles, but you don't have to take them all. The state will consider all proposals, even those seeking one or two trestles for uses such as a walkway over a creek in a public park.

Winners will have to abide by certain restrictions including not allowing vehicular traffic, paying for removal, transportation and lead abatement, and maintaining the features that make the bridge historically significant.

FILE - In this 1942 photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, a Black soldier places dynamite during construction of the Alaska Highway in the Northern Sector of Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

FILE - In this 1942 photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, a Black soldier peers through a surveyor's transit during construction of the Alaska Highway in the Northern Sector of Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

This undated photo provided by the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities shows a trestle bridge, that the state of Alaska is planning to replace, spanning the Gerstle River about 30 miles southeast of Delta Junction. (Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities via AP)

FILE - This Oct. 25, 1942, photo provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History, shows Corporal Refines Slims, Jr., left, and Private Alfred Jalufka shaking hands at the, "Meeting of Bulldozers," for the ALCAN Highway in the Yukon Territory in Beaver Creek, Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

TALLINN, Estonia (AP) — Even now, safely in her new home of Estonia, Inna Vnukova says she can’t purge the terrifying memory of living under Russian occupation in eastern Ukraine early in the war and her family’s harrowing escape.

They hid in a damp basement for days in their village of Kudriashivka after Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022. In the streets, soldiers waving machine guns bullied residents, set up checkpoints and looted homes. There was constant shelling.

“Everyone was very scared and afraid to go outside,” Vnukova told The Associated Press, with troops seeking out Ukrainian sympathizers and civil servants like her and her husband, Oleksii Vnukov.

In mid-March, she decided that she and her 16-year-old son, Zhenya, would flee the village with her brother's family, even though it meant leaving her husband behind temporarily. They took a risky trip by car to nearby Starobilsk, waving a white sheet amid mortar fire.

“We had already said our goodbyes to life, cursing this Russian world,” said Vnukova, 42. “I’ve been trying to forget this nightmare for four years, but I can’t.”

Many Ukrainians like Vnukova fled the invading forces. Those who stayed risked being detained — or worse — as Russian forces eventually took control of about 20% of the country and its estimated 3 million to 5 million people.

After four years of war, life in shattered cities like Mariupol and villages like Kudriashivka remains difficult, with residents facing problems with housing, water, power, heat and health care. Even President Vladimir Putin has acknowledged they have “many truly pressing, urgent problems."

In the illegally annexed regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, Russian citizenship, language and culture is forced on residents, including in school lessons and textbooks. By spring 2025, some 3.5 million people in the four regions had been given Russian passports — a requirement to receive vital services like health care.

Some in the regions say they live in fear of being accused of sympathizing with Ukraine. Many have been imprisoned, beaten and killed, according to human rights activists.

Oleksii Vnukov, a court security officer, stayed behind in the village for nearly two weeks. Russian soldiers twice threatened to kill him, including an instance where he and a friend were dragged off the street by soldiers. But he survived and soon also escaped the village.

The family traveled through Russia before making it to Estonia, where Inna works in a printing house and Oleksii, 43, is an electrician.

“All life is leaving the occupied territories,” Vnukov said. “The people there aren’t living, they’re just surviving.”

Mykhailo Savva of the Center for Civil Liberties in Ukraine said the Russian military's practice of wielding “systemic and total control” in the regions continues today.

“Even though a significant number of socially active people have already been detained, Russian special services continue to identify disloyal Ukrainians, extract confessions, and continue to detain people,” Savva said. “Residents face such practices as document checks, mass searches, and denunciations on a daily basis.”

Human rights groups say Russian authorities used “filtration camps” to identify potentially disloyal individuals, as well as anyone who worked for the government, helped the Ukrainian army or had relatives in the military, along with journalists, teachers, scientists and politicians.

Stanislav Shkuta, 25, who lived in occupied Nova Kakhovka in the Kherson region, said he narrowly escaped arrest several times before reaching Ukrainian-controlled territory in 2023. He recalled being on a bus that was stopped by Russian soldiers.

“It was horrific. Men and women were asked to strip to the waist to see if they had Ukrainian tattoos,” said Shkuta, who now lives in Estonia. “I turned white with fear, wondering if I’d cleared everything on my phone.”

He said his friends who stayed in Nova Kakhovka say life has worsened, with suspected Ukrainian sympathizers stopped on the street or in surprise door-to-door inspections.

“Today, my friends complain that life there has become impossible,” he said.

Russia established a “vast network of secret and official detention centers where tens of thousands of Ukrainian civilians” are held indefinitely without charge, said Oleksandra Matviichuk, head of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Center for Civil Liberties.

“Everyone knows that if you end up in the basement, your life is worth nothing,” she said.

Russian officials have refused to comment on past allegations by U.N. human rights officials that it tortures civilians and prisoners of war.

About 16,000 civilians have been detained illegally, but that number could be much higher because many are held incommunicado. said Ukrainian Human Rights Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets.

A U.N. report released last summer said that between July 2024 and June 2025, it spoke to 57 civilians who were detained in the occupied regions, and that 52 of them told of severe beatings, electric shocks, sexual violence, degradation and threats of violence.

One particularly famous case is that of Ukrainian journalist Victoria Roshchyna, 27, who disappeared in 2023 while reporting near the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant and died in Russian custody. When her body was handed over to Ukraine in 2025, it bore signs of torture, with some of her organs removed, a prosecutor said.

“Russia uses terror in the occupied territories to physically eliminate active people working in certain fields: teachers, children’s writers, musicians, mayors, journalists, environmentalists. It also intimidates the passive majority,” Matviichuk says.

At the start of the war, Russian forces besieged Mariupol before the port city fell in May 2022. The Russian bombing of the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater on March 16 of that year killed close to 600 people in and around the building, an AP investigation found, in the single deadliest known attack against civilians in the war.

Most of the city's population of about a half-million fled but many hid in basements, said a former actor who huddled for months with his parents, saying they were nearly killed by the Russian bombing.

The former actor, now in Estonia, spoke on condition of anonymity to not endanger his 76-year-old parents, still in Mariupol. They had to take Russian citizenship to get medical care, as well as a one-time payment equivalent to $1,300 per person as compensation for their destroyed home, he said.

As in other occupied cities, Russification is taking place in Mariupol, changing street names, teaching Moscow-approved curriculum in schools, using Russian phone and TV networks and putting the city in Moscow's time zone.

“But even today, the threat of death has not gone away. Only those who have Russian passports can survive,″ the former actor said, adding that his parents have asked him not to send postcards in Ukrainian because “it could be dangerous.”

Putin "openly states that there is no Ukrainian language, no Ukrainian culture, no Ukrainian nation. And in the occupied territories, these words are turning into terrible practice,” Matviichuk said.

But not everyone opposes the Russian takeover in Mariupol. The former actor says half of the members of his old troupe now support the Kremlin and believe Kyiv “provoked the war.”

Housing is a sore point in Mariupol, where the population is about half of what it was before 2022. New apartment blocks rose from the ruins, but rather than going to those who lost their homes, they are sold to Russian newcomers.

Some who lost their homes have made video appeals to Putin. “You said we ‘don’t abandon our own.’ Do we not count as your own?” said one resident at a mass rally.

At least 12,191 apartments in Mariupol were added to a list of purportedly “ownerless” and abandoned flats to be expropriated in the first half of 2025. Thousands more are being seized elsewhere.

Moscow is encouraging Russian citizens to move to the occupied regions, offering a range of benefits. Teachers, doctors and cultural workers are promised salary supplements if they commit to living there for five years.

Years of war and neglect have saddled many occupied cities in eastern Ukraine with serious problems in supplying heat, electricity and water.

The northeastern city of Sievierodonetsk suffered significant destruction before falling to Russia in June 2022. Once home to 140,000 people, only 45,000 remain, mostly elderly or disabled.

Only one ambulance crew serves the whole city, and doctors and other health workers rotate in from Russian regions like Perm to work at its hospital, said a 67-year-old former engineer who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution.

But she still supports “the great work Putin is doing,” because she was born and raised in the former Soviet Union.

In Alchevsk, a city in the Luhansk region, over half the homes have been without heat for two bitterly cold months. Five warming stations have been set up and utility companies said over 60% of municipal heating networks are in poor shape, without funds for repairs.

Even a pro-Moscow politician, Oleg Tsaryov, has accused authorities of freezing “an entire city.” When the heating system failed in 2006, he noted on social media that Ukrainian authorities "and the entire country stepped in to help and completely replaced the faulty equipment.” But after the Russian takeover, officials had “contrived to repeat this Armageddon scenario all over again,” he added.

In the Donetsk region, water trucks fill barrels outside apartment blocks — but they freeze solid in winter, said a resident who spoke on condition of anonymity because she feared repercussions.

“There's constant squabbling over water,” she said, adding that lines to get the precious resource are “insane,” and people who are away at work often miss the trucks' arrival.

Donetsk residents wrote an appeal for Putin to intervene in what has become "a humanitarian and environmental catastrophe.”

Putin last year acknowledged the plight in the four regions.

“I know how difficult it is now for the residents of the liberated cities and towns. There are many truly pressing, urgent problems," he said, marking the third anniversary of incorporating those areas into Russia. He cited the need for reliable water supplies and access to health care, among other issues, and said he has launched a "large-scale socioeconomic development program” for the regions.

Meanwhile, Inna Vnukova is building a new life in Estonia: She and Oleksii now have a 1-year-old daughter, Alisa. Their son is now 20.

Only about 150 people — including the couple's parents — remain in the village that once was home to 800, Vnukova said, adding that she would like to show her daughter the family's native Luhansk region someday.

“We’ve been dreaming of returning for four years, but we increasingly wonder — what will we see there?” she asked.

—-

Katie Marie Davies in Manchester, England, contributed.

A view inside Mariupol's Drama Theater on Monday, April 4, 2022, after the landmark was heavily damaged during fighting between Ukrainian and Russian forces that led to Moscow's takeover of the seaside city. (AP Photo, File)

Oleksandra Matviichuk, head of the Center for Civil Liberties, poses in her office in Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, Feb. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Oleksii Vnukov, right, his wife, Inna Vnukova, center left, and their children Evhen, left, and Alisa, pose during an interview with The Associated Press in their apartment in Tallinn, Estonia, Tuesday, Feb. 17, 2026. (AP Photo)

A woman gets drinking water distributed by authorities in the city of Donetsk in the Russian-controlled part of eastern Ukraine, on Thursday, Feb. 19, 2026. (AP Photo)

Civilians gather to receive drinking water distributed by the Russian Emergency Situations Ministry in Mariupol on May 27, 2022, after the seaside city in eastern Ukraine fell to Moscow's troops. (AP Photo, File)