China's brain-computer interface (BCI) industry is fast moving towards clinical usage as innovation and policy support ramps up.

The emerging technology uses implanted devices to collect and process electrical signals generated by neural activities in the patients' cerebral cortex and turns them into signals that can be recognized by a computer, allowing for interconnection and communication between humans, machines and the external environment.

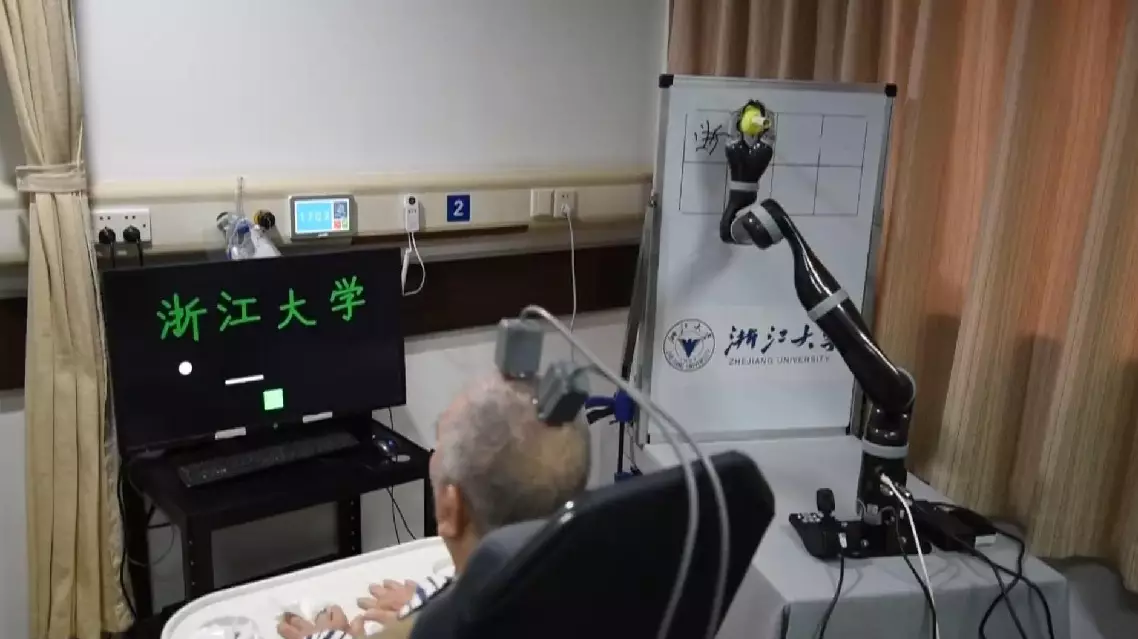

At the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine in east China's Hangzhou City, BCI technology has enabled a 77-year-old patient with high-level paraplegia to write by controlling a robotic arm through a chip inserted in his brain.

"The semi-invasive brain chip is the most accurate in extracting electroencephalograms. We have overcome the most difficult challenge of decoding fine finger movements. Patients with trauma, stroke, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis can control external mechanical devices and write the characters they want," said Zhang Jianmin, a neurosurgery expert at the hospital.

Another successful example of BCI being used in clinical settings is an implantable device, called Neural Electronic Opportunity (NEO), developed by a group of scientists from Tsinghua University.

At Xuanwu Hospital in Beijing, a Chinese clinical team has implanted a minimally-invasive, wireless BCI processor, about the size of two coins, into a participant's skull and successfully acquired the nerve signals in his brain region that control the sensory and motor functions.

After three months of home training, the patient, who has been paralyzed in all four limbs for 14 years, is now capable of fetching a bottle of water on his own via an air-filled glove driven by brain waves, with his grasping accuracy rate exceeding 90 percent.

"We ask the patient to take the bottle to these eight different positions, and then we calculate a time to assess his use of the BCI device. Currently, the patient can, on average, take this water bottle or our object to the designated position within 10 seconds," said Liu Dingkun, a doctoral student at the School of Biomedical Engineering at Tsinghua University.

At Shanghai's Zhongshan Hospital, a patient who is paralyzed following a spinal cord injury is able to stand and walk independently, following the implantation of a brain-spine interface device.

This technology employs epidural electrical stimulation to establish a connection between the brain and the spinal cord, transforming motor goals into muscle activation stimuli. On the first day after surgery, the patient's legs were able to move.

"This technology enables patients to control their legs to take steps with their minds. It is a very important technology for us, because it can help completely paralyzed patients regain the ability to walk," said Ding Jing, director of Neurology Department at Zhongshan Hospital affiliated to Fudan University.

China's National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA) has released a pricing guideline for neural system care services, specifying brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) as an independent category.

According to the NHSA, this move will boost the clinical use of the cutting-edge technology to benefit patients in need, against the backdrop of BCIs' rapid development over recent years.

The guideline also outlines the pricing of invasive and non-invasive BCIs respectively based on the distinctive features of the two BCI approaches.

China makes new breakthroughs in clinical use of brain-computer interfaces