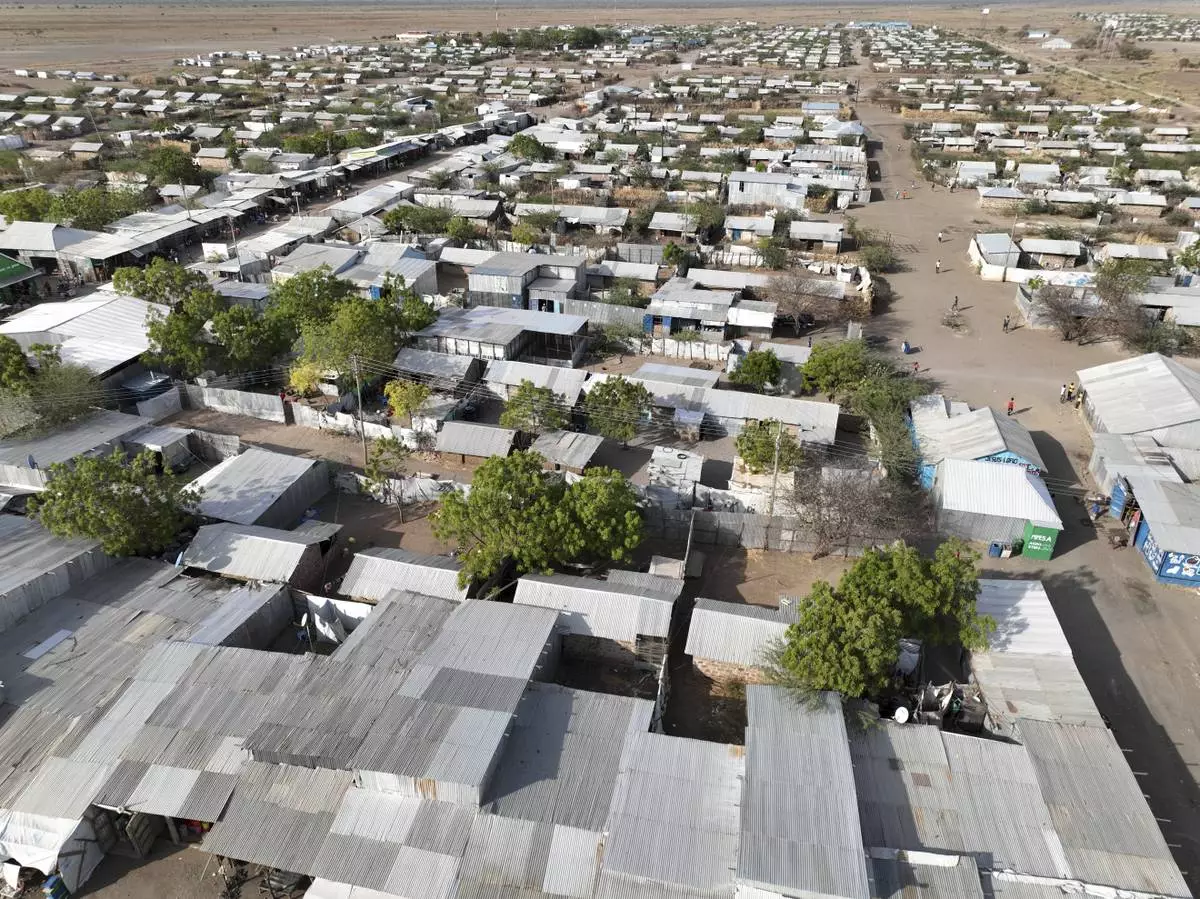

KAKUMA, Kenya (AP) — Windswept and remote, set in the cattle-rustling lands of Kenya’s northwest, Kakuma was never meant to be permanently settled.

It became one of Africa’s most famous refugee camps by accident as people escaping calamity in countries like South Sudan, Ethiopia and Congo poured in.

More than three decades after its first tents appeared in 1992, Kakuma houses 300,000 refugees. Many rely on aid to survive. Some recently clashed with police over shrinking food rations and support.

Now the Kenyan government and humanitarian agencies have come up with an ambitious plan for Kakuma to evolve into a city.

Although it remains under the United Nations' management, Kakuma has been redesignated a municipality, one that local government officials later will run.

It is part of broader goal in Kenya and elsewhere of incorporating refugees more closely into local populations and shifting from prolonged reliance on aid.

The refugees in Kakuma eventually will have to fend for themselves, living off their incomes rather than aid. The nearest city is eight hours' drive away.

Such self-reliance is not easy. Few refugees can become Kenyan citizens. A 2021 law recognizes their right to work in formal employment, but only a tiny minority are allowed to do so.

Forbidden from keeping livestock because of the arid surroundings and the inability to roam widely, and unable to farm due to the lack of adequate water, many refugees see running a business as their only option.

Startup businesses require capital, and interest rates on loans from banks in Kakuma are typically around 20%. Few refugees have the collateral and documentation needed to take out a loan.

Denying them access to credit is a tremendous waste of human capital, said Julienne Oyler, who runs Inkomoko, a charity providing financial training and low-cost loans to African businesses, primarily in displacement-affected communities.

“We find that refugee business owners actually have the characteristics that make world-class entrepreneurs,” she said.

“They are resilient. They are resourceful. They have access to networks. They have adaptability. In some ways, what refugees unfortunately have had to go through actually makes a really good business owner.”

Other options available include microloans from other aid groups or collective financing by refugee-run groups. However, the sums involved are usually insufficient for all but the smallest startups.

One of Inkomoko’s clients in Kakuma, Adele Mubalama, led seven young children — six of her own and an abandoned 12-year-old she found en route — on a hazardous journey to the camp through four countries after the family was forced to leave Congo in 2018.

At the camp it took six months to find her husband, who had fled two months earlier, and six more to figure out how to make a living.

“It was difficult to know how to survive,” Mubalama said. “We didn’t know how to get jobs and there were no business opportunities.”

After signing up for a tailoring course with a Danish charity, she found herself making fabric masks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Able to borrow from Inkomoko at half the rate charged by banks, she expanded, taking on 26 employees and buying new sewing machines. Last year she made a profit of $8,300 — a huge amount when many refugees live on allowances or vouchers of about $10 or less a month.

Another beneficiary is Mesfin Getahun, a former soldier who fled Ethiopia for Kakuma in 2001 after helping students who had protested against the government. He has grown his “Jesus is Lord” shops, which sell everything from groceries to motorcycles, into Kakuma’s biggest retail chain. That's thanks in part to $115,000 in loans from Inkomoko.

Trading with other towns is also essential. Inkomoko has linked refugee businesses with suppliers in Eldoret, a city 300 miles (482 kilometers) to the south, to cut out expensive middlemen and help embed Kakuma into Kenya's economy.

Some question the vision of Kakuma becoming a thriving, self-reliant city.

Rahul Oka, an associate research professor with the University of Notre Dame said it lacks the resources — particularly water — and infrastructure to sustain a viable economy that can rely on local production.

“You cannot reconstruct an organic economy by socially engineering one,” said Oka, who has studied economic life at Kakuma for many years.

Two-way trade remains almost nonexistent. Suppliers send food and secondhand clothes to Kakuma, but trucks on the return journey are usually empty.

And the vast majority of refugees lack the freedom to move elsewhere in Kenya, where jobs are easier to find, said Freddie Carver of ODI Global, a London-based think tank.

Unless this is addressed, solutions offering greater opportunities to refugees cannot deliver meaningful transformation for most of them, he said.

“If you go back 20 years, a lot of refugee rights discourse was about legal protections, the right to work, the right to stay in a country permanently,” Carver said. “Now it’s all about livelihoods and self-sufficiency. The emphasis is so much on opportunities that it overshadows the question of rights. There needs to be a greater balance.”

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

General view of Kakuma refugee camp in Turkana county, Kenya, Saturday, Feb. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Jackson Njehia)

Julienne Oyler, who runs Inkomoko, a charity providing financial training, talks during an interview with the Associated Press Kakuma refugee camp in Turkana county, Kenya, Saturday, Feb. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Jackson Njehia)

Adele Mubalama, holds a cloth at her boutique in Kakuma refugee camp, Turkana County, Kenya, Saturday, Feb. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Jackson Njehia)

General view part of Kakuma refugee camp in Turkana county, Kenya, Saturday, Feb. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Jackson Njehia)