DAKAR, Senegal (AP) — On a recent evening in Senegal 's capital of Dakar, an imam named Ibrahima Diane explained to a group of men why they should be more involved in household chores.

“The Prophet himself says a man who does not help support his wife and children is not a good Muslim,” the 53-year-old said, as he described bathing his baby and helping his wife with other duties.

Click to Gallery

Merchants ride past the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

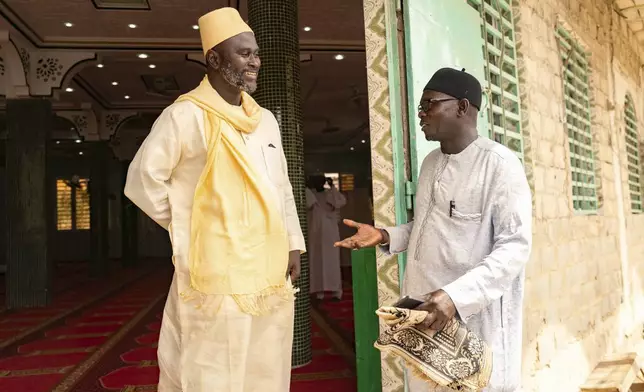

Imam Ibrahima Diane, left, advocate for an end to gender-based violence and practices like female genital mutilation, discusses with El Hadj Malick, coordinator of the "École des Maris" program at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Worshippers listen to Imam Ibrahima Diane, advocate for an end to gender-based violence and practices like female genital mutilation, deliver his sermon at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Merchantswalk past the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Imam Ibrahima Diane, advocate for gender equality and an end to harmful practices like FGM and gender-based violence, poses for a photograph before the start of his sermon at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

El Hadj Malick, coordinator of the "École des Maris" (School for Husbands) program in Pikine, does for a photograph in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

A woman prays in the designated women's section at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Worshippers listen to Imam Ibrahima Diane, advocate for gender equality and an end to harmful practices like FGM and gender-based violence, deliver his sermon at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Some of the 14 men chuckled, not quite sold. Others applauded.

Diane was taking part in a “school for husbands,” a United Nations-backed initiative where respected male community members learn about “positive masculinity” in health and social issues and promote them in their communities.

In Senegal, as in many other West African countries with large rural or conservative populations, men often have the final say in major household decisions, including ones related to health.

Women may need their permission for life-changing decisions on accessing family planning or other reproductive health services, along with hospital deliveries or prenatal care.

Following his sessions at the school for husbands, Diane regularly holds sermons during Friday prayers where he discusses issues around gender and reproductive health, from gender-based violence to fighting stigma around HIV.

“Many women appreciate my sermons," he said. “They say their husbands' behavior changed since they attended them." He said some men have told him the sermons inspired them to become more caring husbands and fathers.

Habib Diallo, a 60-year-old former army commando, said attending the sermons and discussions with the imam taught him about the risks of home births.

“When my son’s wife was pregnant, I encouraged him to take her to the hospital for the delivery,” Diallo said. “At first, he was hesitant. He worried about the cost and didn’t trust the hospital. But when I explained how much safer it would be for both his wife and the baby, he agreed.”

The program launched in Senegal in 2011 but in recent years has caught the attention of the Ministry of Women, Family, Gender and Child Protection, which sees it an effective strategy to combat maternal and infant mortality.

“Without men’s involvement, attitudes around maternal health won’t change," said 54-year-old Aida Diouf, a female health worker who collaborates with the program. Many husbands prefer their wives not be treated by male health workers, she said.

The classes for husbands follow similar efforts in other African countries, particularly Niger, Togo, and Burkina Faso, where the United Nations Population Fund says it improved women’s access to reproductive health services by increasing male involvement, growing the use of contraceptives by both men and women and expanding access to prenatal care and skilled birth attendants.

Discussions for men also have focused on girls’ rights, equality and the harmful effects of female genital mutilation.

The program now operates over 20 schools in Senegal, and over 300 men have been trained.

In some communities, men who once enforced patriarchal norms now promote gender equality, which has led to a reduction in the number of forced marriages and more acceptance of family planning, according to Senegal’s ministry of gender.

Men join the groups after being recruited based on trust, leadership and commitment. Candidates must be married, respected locally and supportive of women’s health and rights.

After training, the men act as peer educators, visiting homes and hosting informal talks.

“My husband used to not do much around the house, just bark orders. Now he actually cooks and helps out with daily tasks,” said Khary Ndeye, 52.

While maternal and infant deaths in Senegal have declined over the past decade, experts say it still has a long way to go. It recorded 237 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births in 2023, while 21 newborns out of every 1,000 died within their first month. The U.N. globally wants to reduce maternal deaths to 70 deaths per 100,000 live births and newborn deaths to under 12 per 1,000 by 2030.

One key problem was that many women have been giving birth at home, said El Hadj Malick, one of the Senegal program’s coordinators.

“By educating men about the importance of supporting their wives during pregnancy, taking them to the hospital and helping with domestic work at home, you’re protecting people’s health,” Malick said.

He said he still experiences difficulty changing mindsets on some issues.

“When we just talk to them about gender, there is sometimes tension because it’s seen as something abstract or even foreign,” Malick said. Some men mistakenly believe such talk will promote LGBTQ+ issues, which remain largely taboo in much of West Africa.

"But when we focus on women’s right to be healthy, it puts a human face on the concept and its becomes universal,” Malick said.

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Merchants ride past the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Imam Ibrahima Diane, left, advocate for an end to gender-based violence and practices like female genital mutilation, discusses with El Hadj Malick, coordinator of the "École des Maris" program at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Worshippers listen to Imam Ibrahima Diane, advocate for an end to gender-based violence and practices like female genital mutilation, deliver his sermon at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Merchantswalk past the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Imam Ibrahima Diane, advocate for gender equality and an end to harmful practices like FGM and gender-based violence, poses for a photograph before the start of his sermon at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

El Hadj Malick, coordinator of the "École des Maris" (School for Husbands) program in Pikine, does for a photograph in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

A woman prays in the designated women's section at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

Worshippers listen to Imam Ibrahima Diane, advocate for gender equality and an end to harmful practices like FGM and gender-based violence, deliver his sermon at the Great Mosque of Nietty Mbar in Thiaroye, a suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Friday, July 4, 2025.(AP Photo/Sylvain Cherkaoui)

HAMIMA, Syria (AP) — A trickle of civilians left a contested area east of Aleppo on Thursday after a warning by the Syrian military to evacuate ahead of an anticipated government military offensive against Kurdish-led forces.

Government officials and some residents who managed to get out said the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces prevented people from leaving via the corridor designated by the military along the main road leading west from the town of Maskana through Deir Hafer to the town of Hamima.

The SDF denied the reports that they were blocking the evacuation.

In Hamima, ambulances and government officials were gathered beginning early in the morning waiting to receive the evacuees and take them to shelters, but few arrived.

Farhat Khorto, a member of the executive office of Aleppo Governorate who was waiting there, claimed that there were "nearly two hundred civilian cars and hundreds of people who wanted to leave” the Deir Hafer area but that they were prevented by the SDF. He said the SDF was warning residents they could face “sniping operations or booby-trapped explosives” along that route.

Some families said they got out of the evacuation zone by taking back roads or going part of the distance on foot.

“We tried to leave this morning, but the SDF prevented us. So we left on foot … we walked about seven to eight kilometers until we hit the main road, and there the civil defense took us and things were good then,” said Saleh al-Othman, who said he fled Deir Hafer with more than 50 relatives.

Yasser al-Hasno, also from Deir Hafer, said he and his family left via back roads because the main routes were closed and finally crossed a small river on foot to get out of the evacuation area.

Another Deir Hafer resident who crossed the river on foot, Ahmad al-Ali, said, “We only made it here by bribing people. They still have not allowed a single person to go through the main crossing."

Farhad Shami, a spokesman for the SDF, said the allegations that the group had prevented civilians from leaving were “baseless.” He suggested that government shelling was deterring residents from moving.

The SDF later issued a statement also denying that it had blocked civilians from fleeing. It said that “any displacement of civilians under threat of force by Damascus constitutes a war crime" and called on the international community to condemn it.

“Today, the people of Deir Hafer have demonstrated their unwavering commitment to their land and homes, and no party can deprive them of their right to remain there under military pressure,” it said.

The Syrian army’s announcement late Wednesday — which said civilians would be able to evacuate through the “humanitarian corridor” from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Thursday — appeared to signal plans for an offensive against the SDF in the area east of Aleppo. Already there have been limited exchanges of fire between the two sides.

Thursday evening, the military said it would extend the humanitarian corridor for another day.

The Syrian military called on the SDF and other armed groups to withdraw to the other side of the Euphrates River, to the east of the contested zone. The SDF controls large swaths of northeastern Syria east of the river.

The tensions in the Deir Hafer area come after several days of intense clashes last week in Aleppo city that ended with the evacuation of Kurdish fighters and government forces taking control of three contested neighborhoods.

The fighting broke out as negotiations have stalled between Damascus and the SDF over an agreement reached last March to integrate their forces and for the central government to take control of institutions including border crossings and oil fields in the northeast.

Some of the factions that make up the new Syrian army, which was formed after the fall of former President Bashar Assad in a rebel offensive in December 2024, were previously Turkey-backed insurgent groups that have a long history of clashing with Kurdish forces.

The SDF for years has been the main U.S. partner in Syria in fighting against the Islamic State group, but Turkey considers the SDF a terrorist organization because of its association with Kurdish separatist insurgents in Turkey.

Despite the long-running U.S. support for the SDF, the Trump administration has also developed close ties with the government of interim Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa and has so far avoided publicly taking sides in the clashes in Aleppo.

Ilham Ahmed, head of foreign relations for the SDF-affiliated Kurdish-led administration in northeast Syria, at a press conference Thursday said SDF officials were in contact with the United States and Turkey and had presented several initiatives for de-escalation. She said that claims by Damascus that the SDF had failed to implement the March agreement were false.

——

Associated Press journalist Hogir Al Abdo in Qamishli, Syria, contributed.

Members of the Syrian military police stand at a humanitarian crossing declared by the Syrian army in the village of Hamima, in the eastern Aleppo countryside, near the front line with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in Deir Hafer, Syria, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Members of the Syrian Civil Defense, stand next to their vehicles at a humanitarian crossing declared by the Syrian army in the village of Hamima, in the eastern Aleppo countryside, near the front line with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in Deir Hafer, Syria, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

A displaced Syrian family rides in the back of a truck near a humanitarian crossing declared by the Syrian army next to a river in the village of Rasm Al-Abboud, in the eastern Aleppo countryside, near the front line with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in Deir Hafer, Syria, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Omar Albam)

Displaced Syrian children and women ride in the back of a truck near a humanitarian crossing declared by the Syrian army in the village of Hamima, in the eastern Aleppo countryside, near the front line with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in Deir Hafer, Syria, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Omar Albam)

Displaced Syrians at a river crossing near the village of Jarirat al Imam, in the eastern Aleppo countryside, near the front line with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in Deir Hafer, Syria, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Omar Albam)