CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (AP) — Blue Origin launched its huge New Glenn rocket Thursday with a pair of NASA spacecraft destined for Mars.

It was only the second flight of the rocket that Jeff Bezos’ company and NASA are counting on to get people and supplies to the moon — and it was a complete success.

Click to Gallery

Spectators on the beach watch a Blue Origin New Glenn rocket as it lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

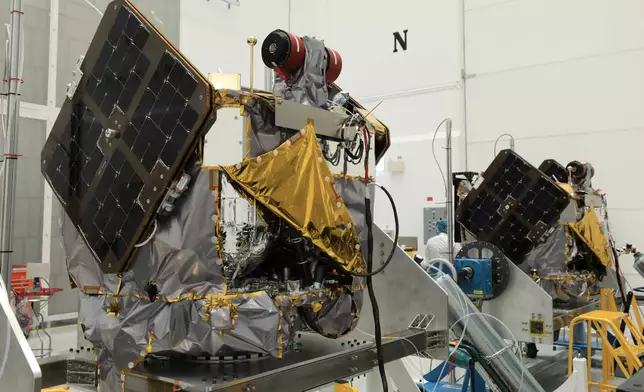

In this image provided by NASA, the agency's identical Mars orbiters, named Escapade (Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers) are inspected and processed at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Aug. 22, 2025. (Kim Shiflett/NASA via AP)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

The 321-foot (98-meter) New Glenn blasted into the afternoon sky from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, sending NASA’s twin Mars orbiters on a drawn-out journey to the red planet. Liftoff was stalled four days by lousy local weather as well as solar storms strong enough to paint the skies with auroras as far south as Florida.

In a remarkable first, Blue Origin recovered the booster following its separation from the upper stage and the Mars orbiters, an essential step to recycle and slash costs similar to SpaceX. Company employees cheered wildly as the booster landed upright on a barge 375 miles (600 kilometers) offshore. An ecstatic Bezos watched the action from Launch Control.

“Next stop, moon!” employees chanted following the booster's bull's-eye landing. Twenty minutes later, the rocket's upper stage deployed the two Mars orbiters in space, the mission's main objective. Congratulations poured in from NASA officials as well as SpaceX's Elon Musk, whose booster landings are now routine.

New Glenn’s inaugural test flight in January delivered a prototype satellite to orbit, but failed to land the booster on its floating platform in the Atlantic.

The identical Mars orbiters, named Escapade, will spend a year hanging out near Earth, stationing themselves 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away. Once Earth and Mars are properly aligned next fall, the duo will get a gravity assist from Earth to head to the red planet, arriving in 2027.

Once around Mars, the spacecraft will map the planet’s upper atmosphere and scattered magnetic fields, studying how these realms interact with the solar wind. The observations should shed light on the processes behind the escaping Martian atmosphere, helping to explain how the planet went from wet and warm to dry and dusty. Scientists will also learn how best to protect astronauts against Mars' harsh radiation environment.

“We really, really want to understand the interaction of the solar wind with Mars better than we do now,” Escapade’s lead scientist, Rob Lillis of the University of California, Berkeley, said ahead of the launch. “Escapade is going to bring an unprecedented stereo viewpoint because we’re going to have two spacecraft at the same time.”

It’s a relatively low-budget mission, coming in under $80 million, that's managed and operated by UC Berkeley. NASA saved money by signing up for one of New Glenn’s early flights. The Mars orbiters should have blasted off last fall, but NASA passed up that ideal launch window — Earth and Mars line up for a quick transit just every two years — because of feared delays with Blue Origin's brand-new rocket.

Named after John Glenn, the first American to orbit the world, New Glenn is five times bigger than the New Shepard rockets sending wealthy clients to the edge of space from West Texas. Blue Origin plans to launch a prototype Blue Moon lunar lander on a demo mission in the coming months aboard New Glenn.

Created in 2000 by Bezos, Amazon's founder, Blue Origin already holds a NASA contract for the third moon landing by astronauts under the Artemis program. Musk’s SpaceX beat out Blue Origin for the first and second crew landings, using Starships, nearly 100 feet (30 meters) taller than Bezos' New Glenn.

But last month NASA Acting Administrator Sean Duffy reopened the contract for the first crewed moon landing, citing concern over the pace of Starship’s progress in flight tests from Texas. Blue Origin as well as SpaceX have presented accelerated landing plans.

NASA is on track to send astronauts around the moon early next year using its own Space Launch System, or SLS, rocket. The next Artemis crew would attempt to land; the space agency is pressing to get astronauts back on the lunar surface by decade’s end in order to beat China.

Twelve astronauts walked on the moon more than a half-century ago during NASA's Apollo program.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Spectators on the beach watch a Blue Origin New Glenn rocket as it lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

In this image provided by NASA, the agency's identical Mars orbiters, named Escapade (Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers) are inspected and processed at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Aug. 22, 2025. (Kim Shiflett/NASA via AP)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

A Blue Origin New Glenn rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 36 at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla., Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/John Raoux)

LONDON (AP) — In France, civil servants will ditch Zoom and Teams for a homegrown video conference system. Soldiers in Austria are using open source office software to write reports after the military dropped Microsoft Office. Bureaucrats in a German state have also turned to free software for their administrative work.

Around Europe, governments and institutions are seeking to reduce their use of digital services from U.S. Big Tech companies and turning to domestic or free alternatives. The push for “digital sovereignty” is gaining attention as the Trump administration strikes an increasingly belligerent posture toward the continent, highlighted by recent tensions over Greenland that intensified fears that Silicon Valley giants could be compelled to cut off access.

Concerns about data privacy and worries that Europe is not doing enough to keep up with the United States and Chinese tech leadership are also fueling the drive.

The French government referenced some of these concerns when it announced last week that 2.5 million civil servants would stop using video conference tools from U.S. providers — including Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Webex and GoTo Meeting — by 2027 and switch to Visio, a homegrown service.

The objective is “to put an end to the use of non-European solutions, to guarantee the security and confidentiality of public electronic communications by relying on a powerful and sovereign tool,” the announcement said.

“We cannot risk having our scientific exchanges, our sensitive data, and our strategic innovations exposed to non-European actors,” David Amiel, a civil service minister, said in a press release.

Microsoft said it continues to “partner closely with the government in France and respect the importance of security, privacy, and digital trust for public institutions.”

The company said it is “focused on providing customers with greater choice, stronger data protection, and resilient cloud services — ensuring data stays in Europe, under European law, with robust security and privacy protections.”

Zoom, Webex and GoTo Meeting did not respond to requests for comment.

French President Emmanuel Macron has been pushing digital sovereignty for years. But there’s now a lot more “political momentum behind this idea now that we need to de-risk from U.S. tech,” Nick Reiners, senior geotechnology analyst at the Eurasia Group.

“It feels kind of like there’s a real zeitgeist shift,” Reiners said

It was a hot topic at the World Economic Forum's annual meeting of global political and business elites last month in Davos, Switzerland. The European Commission's official for tech sovereignty, Henna Virkkunen, told an audience that Europe's reliance on others “can be weaponized against us.”

“That’s why it’s so important that we are not dependent on one country or one company when it comes to very critical fields of our economy or society,” she said, without naming countries or companies.

A decisive moment came last year when the Trump administration sanctioned the International Criminal Court's top prosecutor after the tribunal, based in The Hague, Netherlands, issued an arrest warrant for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, an ally of President Donald Trump.

The sanctions led Microsoft to cancel Khan's ICC email, a move that was first reported by The Associated Press and sparked fears of a “kill switch” that Big Tech companies can use to turn off service at will.

Microsoft maintains it kept in touch with the ICC “throughout the process that resulted in the disconnection of its sanctioned official from Microsoft services. At no point did Microsoft cease or suspend its services to the ICC.”

Microsoft President Brad Smith has repeatedly sought to strengthen trans-Atlantic ties, the company's press office said, and pointed to an interview he did last month with CNN in Davos in which he said that jobs, trade and investment. as well as security, would be affected by a rift over Greenland.

“Europe is the American tech sector’s biggest market after the United States itself. It all depends on trust. Trust requires dialogue,” Smith said.

Other incidents have added to the movement. There's a growing sense that repeated EU efforts to rein in tech giants such as Google with blockbuster antitrust fines and sweeping digital rule books haven't done much to curb their dominance.

Billionaire Elon Musk is also a factor. Officials worry about relying on his Starlink satellite internet system for communications in Ukraine.

Washington and Brussels wrangled for years over data transfer agreements, triggered by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden’s revelations of U.S. cyber-snooping.

With online services now mainly hosted in the cloud through data centers, Europeans fear that their data is vulnerable.

U.S. cloud providers have responded by setting up so-called “sovereign cloud” operations, with data centers located in European countries, owned by European entities and with physical and remote access only for staff who are European Union residents.

The idea is that “only Europeans can take decisions so that they can’t be coerced by the U.S.,” Reiners said.

The German state of Schleswig-Holstein last year migrated 44,000 employee inboxes from Microsoft to an open source email program. It also switched from Microsoft's SharePoint file sharing system to Nextcloud, an open source platform, and is even considering replacing Windows with Linux and telephones and videoconferencing with open source systems.

“We want to become independent of large tech companies and ensure digital sovereignty,” Digitalization Minister Dirk Schrödter said in an October announcement.

The French city of Lyon said last year that it's deploying free office software to replace Microsoft. Denmark’s government and the cities of Copenhagen and Aarhus have also been trying out open-source software.

“We must never make ourselves so dependent on so few that we can no longer act freely,” Digital Minister Caroline Stage Olsen wrote on LinkedIn last year. “Too much public digital infrastructure is currently tied up with very few foreign suppliers.”

The Austrian military said it has also switched to LibreOffice, a software package with word processor, spreadsheet and presentation programs that mirrors Microsoft 365's Word, Excel and PowerPoint.

The Document Foundation, a nonprofit based in Germany that's behind LibreOffice, said the military's switch “reflects a growing demand for independence from single vendors.” Reports also said the military was concerned that Microsoft was moving file storage online to the cloud — the standard version of LibreOffice is not cloud-based.

Some Italian cities and regions adopted the software years ago, said Italo Vignoli, a spokesman for The Document Foundation. Back then, the appeal was not needing to pay for software licenses. Now, it's the main reason is to avoid being locked into a proprietary system.

“At first, it was: we will save money and by the way, we will get freedom,” Vignoli said. “Today it is: we will be free and by the way, we will also save some money.”

Associated Press writer Molly Quell in The Hague, Netherlands contributed to this report.

This version corrects the contribution line to Molly Quell instead of Molly Hague.

FILE - Henna Virkkunen, European Commissioner for Tech-Sovereignty, Security and Democracy gives a press conference at the end of the weekly meeting of the College of Commissioners at EU headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, on April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Omar Havana, File)

French President Emmanuel Macron is seen during the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Tuesday, Jan. 20, 2026. (AP Photo/Markus Schreiber)