Thousands of pages of once-secret court documents show how federal officials and a Virginia court helped an American Marine adopt an Afghan war orphan, in defiance of the U.S. government’s official policy to unite the child with her family.

The Associated Press fought for three years for access to the documents, which reveal how the country’s fractured bureaucracy enabled Marine Joshua Mast and his wife, Stephanie, to adopt the child who was halfway around the globe, being raised by a couple the Afghan government decided were her family.

The records reveal that the federal government and the court have blamed each other for what has become an international incident, which the government says threatens America’s standing in the world and appears as an endorsement of child trafficking.

The baby was orphaned on the battlefield in Afghanistan in 2019. U.S. soldiers pulled her from the rubble and took her to the hospital at an American military base. The U.S. State Department, under President Donald Trump’s first administration, worked with the Afghan government to locate her family.

But the Masts were determined to bring her home, convincing a Virginia judge to grant them an adoption of the girl, who was 7,000 miles away. They then used those adoption documents to take the child from the Afghan family as they fled their homeland during the U.S. military’s chaotic withdrawal in the summer of 2021.

Here are takeaways from the documents.

The documents reveal that the adoption the Fluvanna County court granted the Masts skipped legal safeguards meant to protect children. There is no Virginia law that allows a judge to adopt out a foreign child without her home country’s consent.

Yet Fluvanna County Circuit Court Judge Richard Moore did just that. He relied on the word of Mast to declare that the child was “stateless.”

Lawyers representing the government, the Afghan family and the child would note many defects in these proceedings; the attorney representing the child’s best interests described the flaws as “glaring.” A child must be put up for adoption by a parent or agency, and this child had never been. The court waived the requirement that the child be present when social services visited the adoptive parents’ home, that someone investigate her history, that whoever had custody be told this was happening.

Even Moore acknowledged the flaws in the adoption he’d granted. He wrote in a 38-page opinion he published before retiring that there was “procedural irregularity, defect or deficiency in the case.”

“I’ll probably think about this the rest of my life whether I should have said, sorry, that child is in Afghanistan. We’re just going to stand down,” Moore said at a hearing. “I don’t know whether that’s what I should have done.”

Moore said there were things he wished he’d known when he granted the adoption in December 2020, declaring the child “an undocumented, orphan, stateless minor.”

The federal government insisted it received no notice of Mast’s bid for adoption, the recently released records show. Had it been notified, government lawyers said, they would have told the judge that the child was not stateless, the government was at that time searching for her family and would soon decide she was Afghan and not the child of foreigners.

She was also not in a medical crisis: A month before, exhibits show, her doctor described her as “a healthy healing infant who needs normal infant care.”

The judge said he never knew that a federal judge had rejected the Masts’ attempt to block the U.S. government from sending the girl to her Afghan relatives. Mast told Moore the child was given to an unmarried teenage girl whose relationship to her was unclear. He testified that he maintained the child was the daughter of foreign fighters.

An Army colonel wrote in a court declaration that the military had decided Mast was “attempting to interfere inappropriately,” and the military and State Department worked to keep him away from the child.

But others within the same agencies helped him.

At Mast’s request, the military evacuated the Afghan family from Afghanistan during America’s chaotic withdrawal in the summer of 2021. They were put in line with Afghans who had helped the U.S. military. They never had; their only reason to be added to the list was Mast’s desire to bring the baby to the U.S.

Government employees working at a refugee resettlement center in Virginia took Mast’s adoption documents at face value, never learning their own government had already dismissed them as “flawed” and rejected Mast’s claim to the child. A State Department employee was ordered by her supervisors to physically take the child from the Afghans and hand her to the Masts, as the Afghan woman collapsed onto the floor weeping.

—-

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/.

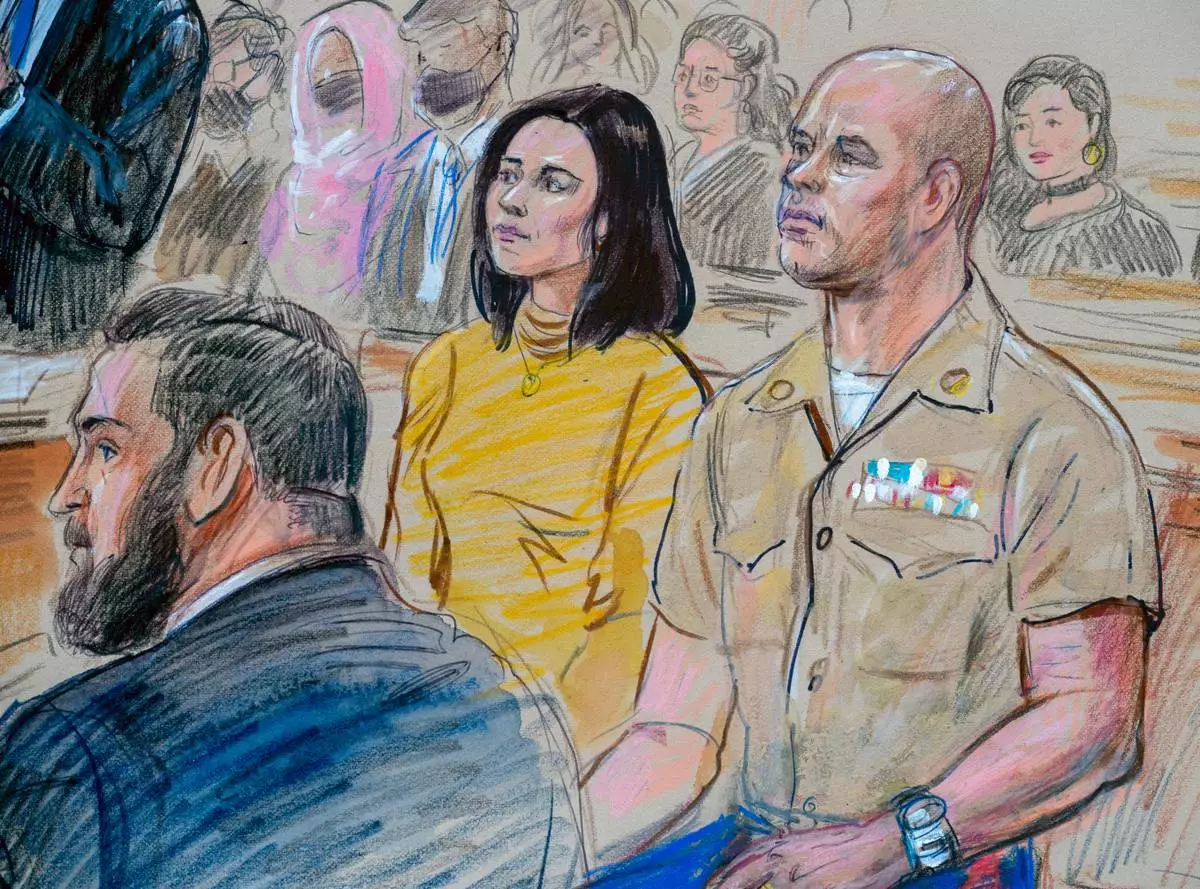

FILE - Marine Maj. Joshua Mast and his wife, Stephanie, arrive at Circuit Court, Thursday, March 30, 2023, in Charlottesville, Va. (AP Photo/Cliff Owen, File)

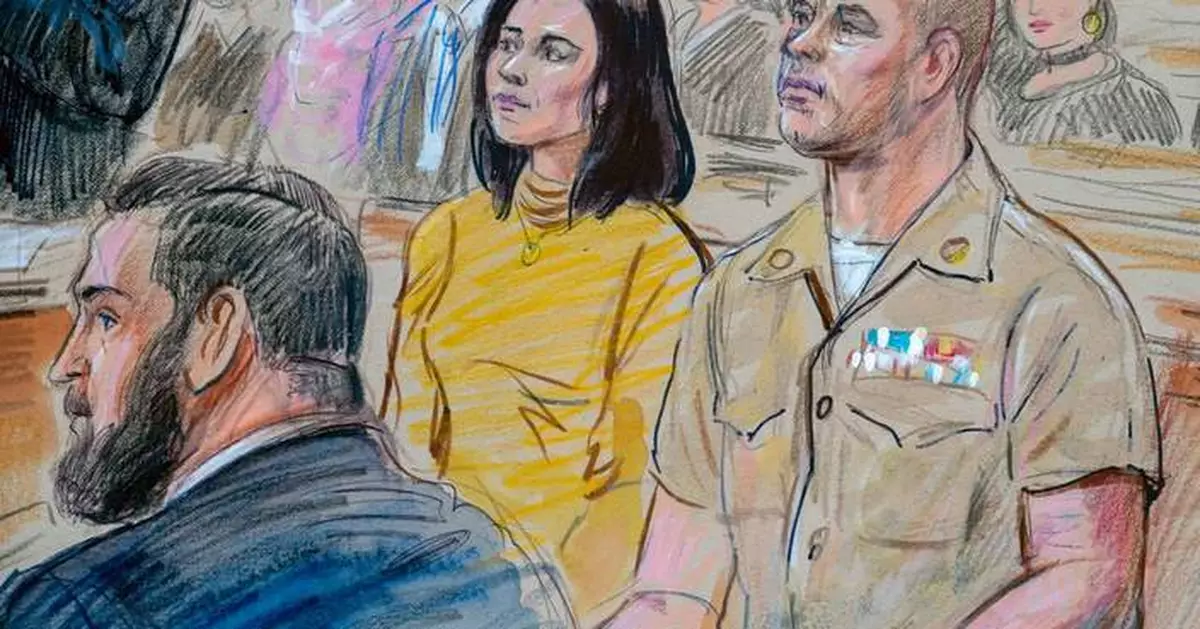

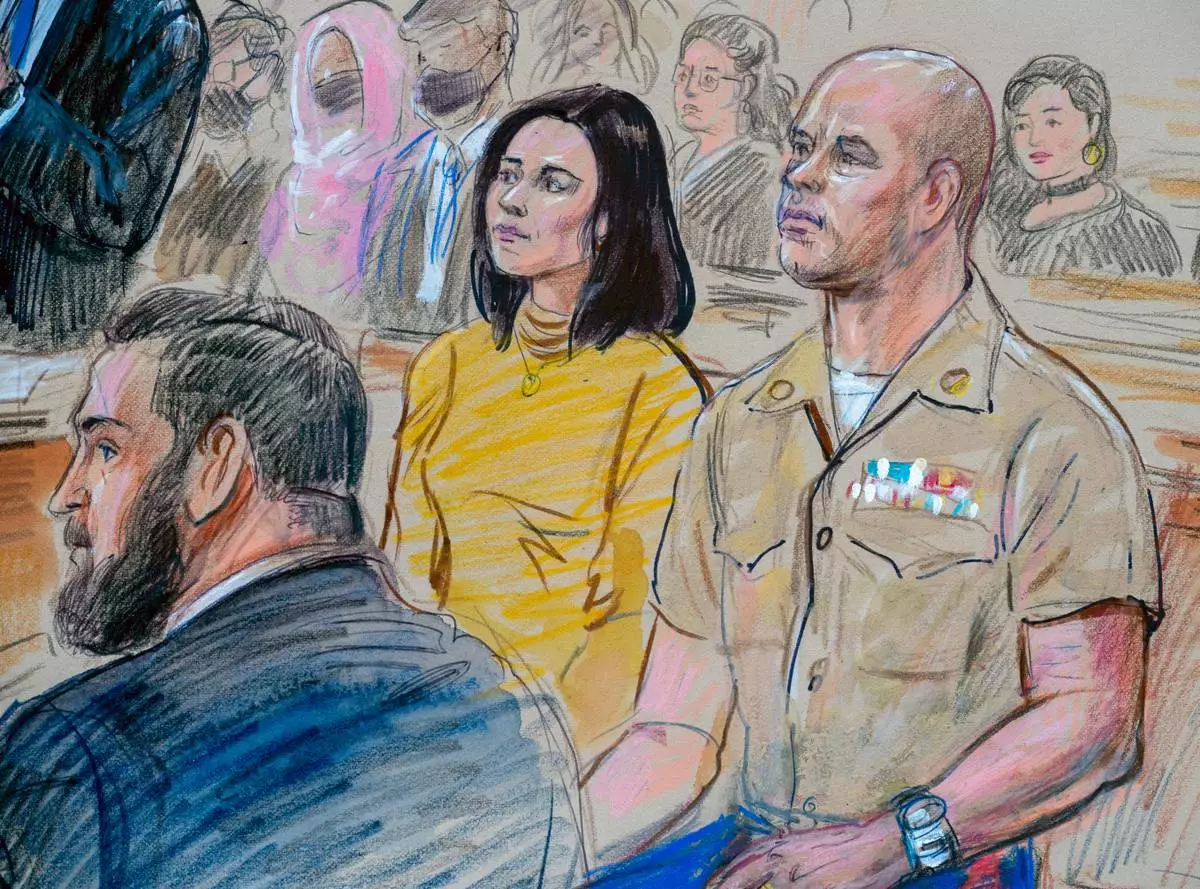

FILE - This artist sketch depicts Marine Maj. Joshua Mast and his wife, Stephanie, listening during a Circuit Court hearing before Judge Claude V. Worrell Jr., Thursday, March 30, 2023, in Charlottesville, Va. (Dana Verkouteren via AP)

AL-HOL, Syria (AP) — Basic services at a camp in northeast Syria holding thousands of women and children linked to the Islamic State group are returning to normal after government forces captured the facility from Kurdish fighters, a United Nations official said on Thursday.

Forces of Syria’s central government captured al-Hol camp on Jan. 21 during a weekslong offensive against the Kurdish-led and U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF, that had been running the camp near the border with Iraq for a decade. A ceasefire deal has since ended the fighting.

Celine Schmitt, a spokesperson for the U.N. refugees agency told The Associated Press that the interruption of services occurred for two days during the fighting around the camp.

She said a UNHCR team visited the recaptured came to establish “very quickly the delivery of basic services, humanitarian services,” including access to health centers. Schmitt said that as of Jan. 23, they were able to deliver bread and water inside the camp.

Schmitt, speaking in Damascus, said the situation at al-Hol camp has been calm and some humanitarian actors have also been distributing food parcels. She said that government has named a new administrator for the camp.

At its peak after the defeat of IS in Syria in 2019, around 73,000 people were living at al-Hol. Since then the number has declined with some countries repatriating their citizens. The camp’s residents are mostly children and women, including many wives or widows of IS members.

The camp's residents are not technically prisoners and most have not been accused of crimes, but they have been held in de facto detention at the heavily guarded facility.

The current population is about 24,000, including 14,500 Syrians and nearly 3,000 Iraqis. About 6,500 from other nationalities are held in a highly secured section of the camp, many of whom are IS supporters who came from around the world to join the extremist group.

The U.S. last month began transfering some of the 9,000 IS members from jails in northeast Syria to Iraq. Baghdad said it will prosecute the transfered detainees. But so far, no solution has been announced for al-Hol camp and the similar Roj camp.

Amal al-Hussein of the Syria Alyamama Foundation, a humanitarian group, told the AP that all the clinics in the camp's medical facility are working 24 hours a day, adding that up to 150 children and 100 women are treated daily.

She added that over the past 10 days there have been five natural births in the camp while cesarean cases were referred to hospitals in the eastern province of Deir el-Zour or al-Hol town.

She said that there are shortages of baby formula, diapers and adult diapers in the camp.

A resident of the camp for eight years, who spoke on condition of anonymity due to concerns over the safety of her family, said there have been food shortages, while the worst thing is a lack of proper education for her children.

“We want clothes for the children, as well as canned food, vegetables and fruits,” she said, speaking inside a tent surrounded by three of her daughters, adding that the family has not had vegetables and fruits for a month because the items are too expensive for most of the camp residents.

Mariam al-Issa, from the northern Syrian town of Safira, said she wants to leave the camp along with her children so that thy can have proper education and eat good food.

“Because of the financial conditions we cannot live well,” she said. “The food basket includes lentils but the children don’t like to eat it any more.”

“The children crave everything,” al-Issa said, adding that food at the camp should be improved from mostly bread and water. “It has been a month since we didn’t have a decent meal,” she said.

Thousands of Syrians and Iraqis have returned to their homes in recent years, but many only return to find destroyed homes and no jobs as most Syrians remain living in poverty as a result of the conflict that started in March 2011.

Schmitt said investment is needed to help people who return home to feel safe. “They need to get support in order to have a house, to be able to rebuild a house in order to have an income,” she said.

“Investments to respond and to overcome the huge material challenges people face when they return home,” she added.

This story was published Feb. 5, 2026, and updated Feb. 6 to remove the name of a camp resident who requested anonymity due to concerns over the safety of her family.

Shaheen reported from Damascus.

Women receive medication and treatment for their children at a medical center in the al-Hol camp, one of the detention facilities holding thousands of Islamic State group members and their families, now under the control of the Syrian government following the withdrawal of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in al-Hassakeh province, northeastern Syria, Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

An aerial view shows the town of al-Hol and, in the background, the camp, which holds thousands of Islamic State group members and their families and is now under the control of the Syrian government following the withdrawal of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in al-Hassakeh province, northeastern Syria, Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Residents walk along the al-Hol camp, one of the detention facilities holding thousands of Islamic State group members and their families, now under the control of the Syrian government following the withdrawal of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in al-Hassakeh province, northeastern Syria, Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Women wait at a medical center in the al-Hol camp, one of the detention facilities holding thousands of Islamic State group members and their families, now under the control of the Syrian government following the withdrawal of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in al-Hassakeh province, northeastern Syria, Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)