What to know about the protests shaking Iran as government shuts down internet and phone networks

China welcomes foreign enterprises, long-term capital to continue expanding investment in China: vice premier

Labour Department Investigates Fatal Construction Accident in Kai Tak, Urges Enhanced Safety Measures

What to know about the protests shaking Iran as government shuts down internet and phone networks

China welcomes foreign enterprises, long-term capital to continue expanding investment in China: vice premier

Labour Department Investigates Fatal Construction Accident in Kai Tak, Urges Enhanced Safety Measures

Feature · News

Internet services partially resume, sufficient daily supplies available in Iran's Tehran

Xi emphasizes commitment to multilateralism, cooperation in latest diplomatic engagements

China to roll out new policy package to further boost consumption, expand domestic market

Chinese stock markets continue to rally as trading turnover hits record high: analyst

AI-powered service platforms improve consumer experiences in China

What to know about the Chicago doctor charged with murdering his ex-wife and her husband

Tech companies lead Hong Kong shares rally on Monday: analyst

HK Express Soars as World's Safest Budget Airline Again

China issues landmark regulation on allocation of government investment funds

China issues new regulation to guide development of gov't investment funds

People rally around the world in support of protests in Iran, in photos

Iran ready for talks with US based on mutual respect: FM

Displaced Aleppo residents return home after days of intense clashes

What to know about the state gerrymandering battle kick-started by Trump

Here's how AP reports on the death toll from Iran's protests

Photos of Syrians fleeing violence in Aleppo as shelling leaves heavy damage

Tech companies lead Hong Kong shares rally on Monday: analyst

HK Express Soars as World's Safest Budget Airline Again

China issues landmark regulation on allocation of government investment funds

China issues new regulation to guide development of gov't investment funds

Internet services partially resume, sufficient daily supplies available in Iran's Tehran

Xi emphasizes commitment to multilateralism, cooperation in latest diplomatic engagements

China to roll out new policy package to further boost consumption, expand domestic market

Chinese stock markets continue to rally as trading turnover hits record high: analyst

AI-powered service platforms improve consumer experiences in China

What to know about the Chicago doctor charged with murdering his ex-wife and her husband

People rally around the world in support of protests in Iran, in photos

Iran ready for talks with US based on mutual respect: FM

Displaced Aleppo residents return home after days of intense clashes

What to know about the state gerrymandering battle kick-started by Trump

Here's how AP reports on the death toll from Iran's protests

Photos of Syrians fleeing violence in Aleppo as shelling leaves heavy damage

Feature·Bloggers

【What Say You?】The Gavel vs. The Sanction: Hong Kong’s Judiciary Stands Firm

【Bastille Commentary】Chicken-hearted Conservatives: Sanctioning Hong Kong Judges While Trump Runs Wild

【What Say You?】Trump’s “Maduro Grab” Gets a Glossy Spin by the Usual Suspects

【What Say You?】Trump's Judicial Theater: Maduro's Fate Already Sealed

【Deep Throat】Trump's Venezuelan Oil Grab: Big Oil Not Playing Along?

The Most Laughable Lie of the New Year: Jimmy Lai's "Grave Illness" Falls Apart Under Five Hard Facts

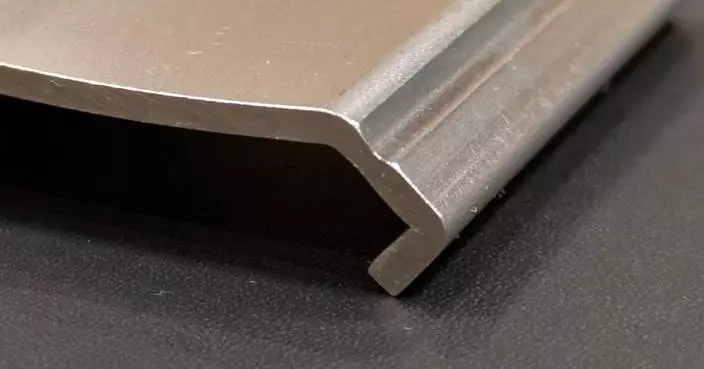

NIPPON KINZOKU Launches Full-Scale Expansion of “Eco-Product” Using Innovative Composite Metal Forming Technology Based on “Fine Profile”

- Photos of tensions between federal officers and locals in Minneapolis

- DOJ investigation of Fed Chair Powell sparks backlash, support for Fed independence

- Pentagon is embracing Musk's Grok AI chatbot as it draws global outcry

- The Latest: Trump says Iran proposed negotiations as hundreds killed in protests

- Minnesota and the Twin Cities sue the federal government to stop the immigration crackdown

- Man accused of recklessly driving U-Haul into Iran protest in Los Angeles, police say

- PBS weekend newscasts shut down due to funding cuts, replaced by single-topic programs

- Zohran Mamdani and his wife move into NYC mayoral mansion, leaving behind 1-bedroom apartment

- Trump holds off on military action against Iran's protest crackdown as he 'explores' Tehran messages

Chinese yuan strengthens to 7.0103 against USD Tuesday

- U.S. dollar ticks down

- Somalia revokes all pacts with UAE amid diplomatic rifts

- Tensions escalate as IDF operations continue in Gaza, West Bank

- U.S. desire to take over Greenland unacceptable: Greenland government

- Iran's nationwide demonstrations oppose U.S., Israel interference

- Mossad agents attempt to direct terrorist acts: Iranian FM

- China, Canada should leverage complementarity for mutual benefit: former Canadian PM

- China, EU agree on price undertaking guidance for Chinese electric vehicle exporters: commerce ministry

- Xi urges advancing Party self-governance with higher standards, more concrete measures

AISpeech's Smart Mobility Solutions Debut at CES 2026

- ETO Markets Strengthens Global Compliance Framework with Mauritius FSC License

- SHAREit Group Upgrades to AI-Powered Mobile Ad Platform to Drive Growth in Emerging Markets

- Wyndham Enhances Position in South Korea with First Managed Hotel Opening

- Schaeffler appoints Maximilian Fiedler as Regional Chief Executive Officer Asia/Pacific

- Court says Trump admin illegally blocked billions in clean energy grants to Democratic states

- HDBank completes issuance of US$100 million green bonds to international investors

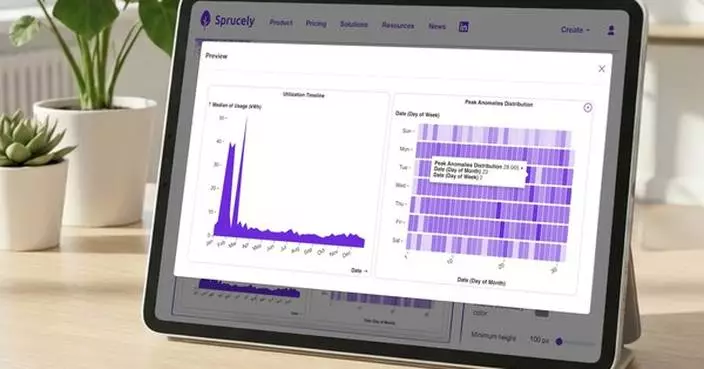

- Sprucely.io Launches AI-Generated Analytics Dashboards Professional Teams Can Deploy in Seconds

- From Engineering Feats to Ecological Regeneration, Vinhomes Green Paradise Debuts the ESG++ Framework for Future Cities

- Black Box Names Sameer Batra as Chief Business Officer to accelerate International Markets Growth

Apple calls on Google to help smarten up Siri and bring other AI features to the iPhone

- Meta names former Trump adviser Dina Powell McCormick as president and vice chairman

- Malaysia and Indonesia become the first countries to block Musk’s Grok over sexualized AI images

- Google teams up with Walmart and other retailers to enable shopping within Gemini AI chatbot

- VR headsets are 'hope machines' inside California prisons, offering escape and practical experience

- Doctors say changes to US vaccine recommendations are confusing parents and could harm kids

- Strength training is crucial after menopause. How to make the most of your workouts

- Meta lines up massive supply of nuclear power to energize AI data centers

- From climbing vacuums to cyber pets: Some highlights of CES 2026

- Musk's Grok chatbot restricts image generation after global backlash to sexualized deepfakes

'Joe Dirt' tribute takes top prize in Pennsylvania Farm Show mullet contest

- Music honcho L.A. Reid settles with ex-recording executive who accused him of sexual assault

- Celebrities embrace black and old Hollywood glamour for Golden Globes red carpet

- Milan prison hosts concert with instruments made by inmates from migrant smugglers’ boats

- Celebrity birthdays for the week of Jan. 18-24 includes Mariska Hargitay and Dolly Parton

- Inside the Golden Globes: The reunions and moments the telecast didn't show

- Photos of 20-year-olds gathering in kimonos for Coming of Age Day ceremony in Japan

- See top photos of stars on the 2026 Golden Globe Awards red carpet

- Golden Globe highlights: Brazil on a streak, Amy Poehler's pod wins and Seth Rogen comes full-circle

- Celebrities wear pins protesting ICE at the Golden Globes

Canadiens defeat Canucks 6-3 with 3-goal outburst in third period

- Maxey scores 33 as 76ers use 80-point first half to beat Raptors 115-102

- Copp scores in OT, lifts Red Wings to 4-3 win over Hurricanes after retiring Sergei Fedorov's jersey

- Keyonte George shines as Jazz defeat Cavaliers 123-112

- Catton scores tiebreaking goal in 3rd period as Kraken rally from 2 goals down and beat Rangers 4-2

- Lightning beat Flyers for 10th straight win as Cooper notches 600th win

- Pascal Siakam and Pacers nip Celtics 98-96 for 1st 3-game win streak of season

- Jazz bounce back after a 55-point loss and beat Cavaliers 123-112

- What to know about Brooks Koepka's return to the PGA Tour after 4 years with LIV Golf

- Seahawks begin preparing for 49ers after both coordinators interview for head coaching jobs

Owner Fined $66,040 for Ignoring Building Removal Order in Tuen Mun Case

- Fatal Traffic Accident in Sham Shui Po Claims Life of 48-Year-Old Driver

- Chan Kin-por Suspends Public Roles to Focus on Wang Fuk Court Fire Investigation

- Civil Aviation Department Completes Successful Aeronautical Search and Rescue Exercise Near Lantau Island

- HKMA Warns Public About Scams Involving Fraudulent Bank Websites and Phishing Emails

- No New Chikungunya Fever Cases Reported in Hong Kong; Authorities Enhance Mosquito Control Measures

- Hong Kong Launches Special Care Dental Services Coordinating Committee to Enhance Oral Health for Targeted Groups

- FEHD Launches Anti-Rodent Partner Awards 2026, Inviting Nominations Until February 11

- Centre for Health Protection Reports Two Legionnaires' Disease Cases, Urges Public to Maintain Water Systems

- Hong Kong Customs Seizes 11.5 kg of Cannabis in Two Airport Drug Trafficking Cases

Death toll in central Philippine landfill collapse rises to eight

- Head coach says he has patience to lead Chinese team toward World Cup

- Iranian foreign minister says situation "fully under control," accuses Israeli intelligence of stoking unrest

- Capital market must coordinate investment, financing: expert

- Russian visitors drawn to south China's Sanya by sun, sea, healthcare

- Venezuelan acting president calls for national unity amid complex situation

- Danish expert urges global response to U.S. threat over Greenland

- US military action against Venezuela draws widespread condemnation

- China's men's national football team goes all out in preparation for 2027 Asia Cup

- U.S. Fed Chair Powell under investigation

Category · News

Canadiens defeat Canucks 6-3 with 3-goal outburst in third period

AISpeech's Smart Mobility Solutions Debut at CES 2026

Chinese yuan strengthens to 7.0103 against USD Tuesday

Maxey scores 33 as 76ers use 80-point first half to beat Raptors 115-102

Copp scores in OT, lifts Red Wings to 4-3 win over Hurricanes after retiring Sergei Fedorov's jersey

Keyonte George shines as Jazz defeat Cavaliers 123-112

U.S. dollar ticks down

Catton scores tiebreaking goal in 3rd period as Kraken rally from 2 goals down and beat Rangers 4-2

Lightning beat Flyers for 10th straight win as Cooper notches 600th win

ETO Markets Strengthens Global Compliance Framework with Mauritius FSC License

Pascal Siakam and Pacers nip Celtics 98-96 for 1st 3-game win streak of season

Owner Fined $66,040 for Ignoring Building Removal Order in Tuen Mun Case

NIPPON KINZOKU Launches Full-Scale Expansion of “Eco-Product” Using Innovative Composite Metal Forming Technology Based on “Fine Profile”

Photos of tensions between federal officers and locals in Minneapolis

Jazz bounce back after a 55-point loss and beat Cavaliers 123-112

SHAREit Group Upgrades to AI-Powered Mobile Ad Platform to Drive Growth in Emerging Markets

DOJ investigation of Fed Chair Powell sparks backlash, support for Fed independence

Pentagon is embracing Musk's Grok AI chatbot as it draws global outcry

Wyndham Enhances Position in South Korea with First Managed Hotel Opening

What to know about Brooks Koepka's return to the PGA Tour after 4 years with LIV Golf

Schaeffler appoints Maximilian Fiedler as Regional Chief Executive Officer Asia/Pacific

Seahawks begin preparing for 49ers after both coordinators interview for head coaching jobs

The Latest: Trump says Iran proposed negotiations as hundreds killed in protests

Minnesota and the Twin Cities sue the federal government to stop the immigration crackdown

Somalia revokes all pacts with UAE amid diplomatic rifts

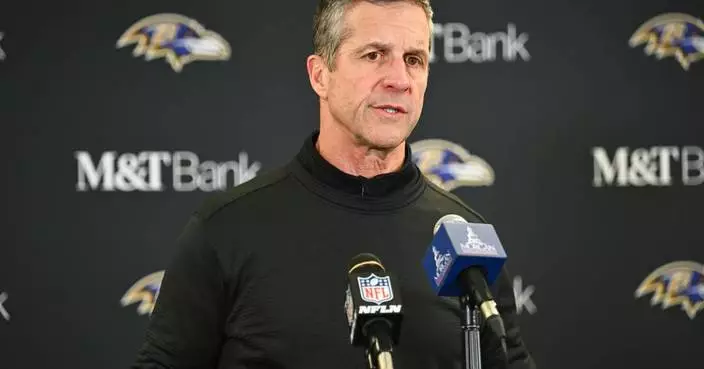

Falcons interview John Harbaugh and Mike McDaniel as they continue search to replace Raheem Morris

Man accused of recklessly driving U-Haul into Iran protest in Los Angeles, police say

Cameron Knowles promoted to coach of Major League Soccer's Minnesota United

PBS weekend newscasts shut down due to funding cuts, replaced by single-topic programs

Zohran Mamdani and his wife move into NYC mayoral mansion, leaving behind 1-bedroom apartment

Trump holds off on military action against Iran's protest crackdown as he 'explores' Tehran messages

Tensions escalate as IDF operations continue in Gaza, West Bank

Red Wings retire Sergei Fedorov's No. 91 jersey and he says leaving Detroit was a huge mistake

Brooks Koepka is coming back to the PGA Tour. Here's what some of his peers think

The Latest: Minnesota and the Twin Cities sue federal government to stop immigration crackdown

Blackhawks forward Connor Bedard scratched for game against Oilers due to an illness

AI Takes Airport Travel as 1ST Airport Taxis and UK Hubs Turn to Predictive Technology

Mississippi man accused of killing 6 people, including a 7-year-old, pleads not guilty

Court says Trump admin illegally blocked billions in clean energy grants to Democratic states

U.S. desire to take over Greenland unacceptable: Greenland government

Doctor charged in killings of his ex-wife and her Ohio husband waives right to extradition hearing

Uvalde teacher who survived class shooting testifies he saw 'black shadow with a gun'

How NATO works at a time when Trump is threatening to seize Greenland

Australia captain Alyssa Healy plans to retire after India series

Beshear: Focusing on everyday concerns is key for Democrats vying for governorships

Sprucely.io Launches AI-Generated Analytics Dashboards Professional Teams Can Deploy in Seconds

From Engineering Feats to Ecological Regeneration, Vinhomes Green Paradise Debuts the ESG++ Framework for Future Cities

HDBank completes issuance of US$100 million green bonds to international investors

FBI says it has found no video of Border Patrol agent shooting 2 people in Oregon

Iran's nationwide demonstrations oppose U.S., Israel interference

Drone strike kills 3 in Gaza as Hamas prepares to transfer governance to new committee

NHL chooses Buffalo Sabres to host draft in June with PSU's Gavin McKenna as the top prospect

Colombian rebels call for a 'national accord' after the US intervention in Venezuela

US lawmakers to visit Denmark as Trump continues to threaten Greenland

$182M settlement reached in 2015 commuter train crossing crash that killed 6 in New York

Sen. Kelly sues the Pentagon over attempts to punish him, declaring it unconstitutional

US accuses Russia of 'dangerous and inexplicable escalation' of war in Ukraine as Trump seeks peace

What to know about the warrants most immigration agents use to make arrests

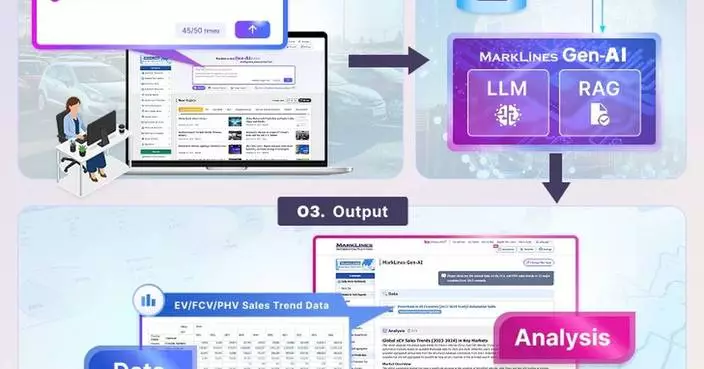

MarkLines Gen-AI Beta Version Released for Automotive Industry

Black Box Names Sameer Batra as Chief Business Officer to accelerate International Markets Growth

NHL and NHLPA say they're pleased after test events at new Olympic hockey arena in Milan

Former Pittsburgh Pirates reliever Dave Giusti, who helped win the 1971 World Series, dies at 86

New video shows the minutes before immigration officer fatally shoots woman in Minneapolis

FBI says arson suspect targeted Mississippi synagogue because it's a Jewish house of worship

Packers' inability to protect leads down the stretch proves costly in wild-card loss at Chicago

Szoboszlai the hero and villain as Liverpool overcome Barnsley in engrossing FA Cup match

WNBA, players' union agree to moratorium, halting initial stages of free agency

'Joe Dirt' tribute takes top prize in Pennsylvania Farm Show mullet contest

Brooks Koepka returns to PGA Tour under stiff financial penalty just 5 weeks after leaving LIV Golf

Tineco's Modern Living Vision Earns Global Media Recognition at CES 2026

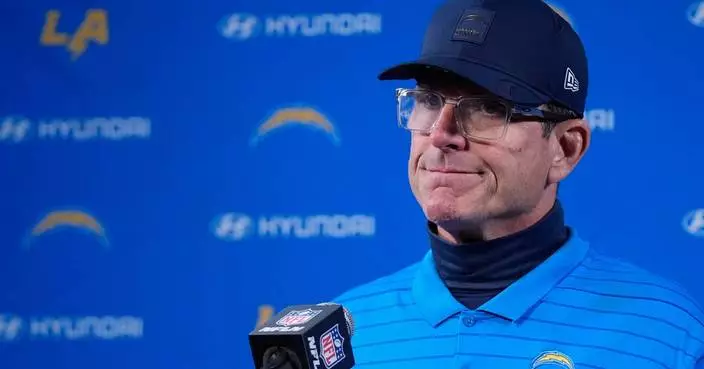

Chargers could see changes to roster and coaching staff after another one-and-done postseason

Koepka says he has 'a lot of work to do' with PGA Tour players upon his return

Walker & Dunlop Expands Capital Markets Presence in Miami

Families of prisoners in Venezuela wait in anguish as promised releases trickle

Boston's Jaylen Brown said 'Give me the fine.' NBA delivers $35,000 penalty for criticizing refs

Georgia prison fight kills 3 inmates and injures over a dozen, including a guard

Offshore wind developer prevails in court as Trump says the US 'will not approve any windmills'

Mossad agents attempt to direct terrorist acts: Iranian FM

Vrabel and Patriots bring confidence into divisional round after strong defensive performance

Real Madrid gets rid of Xabi Alonso and promotes B team manager Álvaro Arbeloa

Trump says Iran wants to negotiate as the death toll in protests rises to at least 572

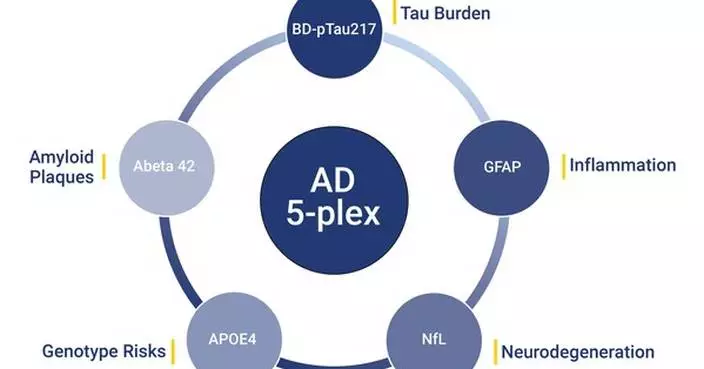

Alamar Biosciences Announces Launch of NULISAqpcr™ AD 5-plex Assay, Advancing Blood Based Biomarker Detection in Alzheimer's Disease Research

Bears coach Ben Johnson offers no apologies for profane postgame speech

Susan Steinhoff Appointed Chief Underwriting Officer at Hamilton Re