Feature · News

Internet services partially resume, sufficient daily supplies available in Iran's Tehran

Former US official denounces American military action against Venezuela as illegal, violation of international law

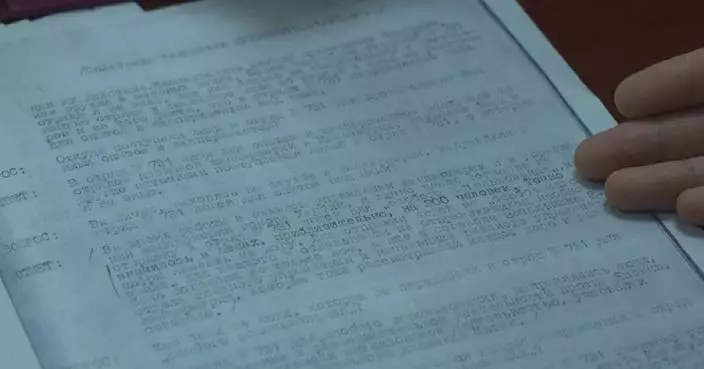

Evidence reveals transfer of live humans for experiments by Unit 731 of WWII Japanese forces

China vows effective punishment against Taiwan separatists

Israel plans to launch new round of strikes on Gaza Strip: media

Iranian president says government focusing on ensuring supplies amid protests

BP China Insight : Former U.S. Ambassador to NATO: Trump Obsessed with Oil; China Bets on Electricity

BP China Insight : Japan Seeks "Parental" U.S. Help After Repeated Chinese Retaliation

Protests erupt in Los Angeles against ICE, U.S. actions in Venezuela

UN chief calls for respect for international law in response to Trump’s remarks

Photos of Syrians fleeing violence in Aleppo

Bublik Blazes to the Bank of China Hong Kong Tennis Open, Musetti Doubles Delight

Autonomous vehicles drive HK forward

Man United crashes out of FA Cup as club weighs up candidates for interim coach

Wildfires in south Argentina rip through nearly 12,000 hectares of forest, threatening communities

First responders enter devastated Aleppo neighborhood after days of deadly fighting

BP China Insight : Former U.S. Ambassador to NATO: Trump Obsessed with Oil; China Bets on Electricity

BP China Insight : Japan Seeks "Parental" U.S. Help After Repeated Chinese Retaliation

Protests erupt in Los Angeles against ICE, U.S. actions in Venezuela

UN chief calls for respect for international law in response to Trump’s remarks

Internet services partially resume, sufficient daily supplies available in Iran's Tehran

Former US official denounces American military action against Venezuela as illegal, violation of international law

Evidence reveals transfer of live humans for experiments by Unit 731 of WWII Japanese forces

China vows effective punishment against Taiwan separatists

Israel plans to launch new round of strikes on Gaza Strip: media

Iranian president says government focusing on ensuring supplies amid protests

Photos of Syrians fleeing violence in Aleppo

Bublik Blazes to the Bank of China Hong Kong Tennis Open, Musetti Doubles Delight

Autonomous vehicles drive HK forward

Man United crashes out of FA Cup as club weighs up candidates for interim coach

Wildfires in south Argentina rip through nearly 12,000 hectares of forest, threatening communities

First responders enter devastated Aleppo neighborhood after days of deadly fighting

Feature·Bloggers

【Bastille Commentary】Chicken-hearted Conservatives: Sanctioning Hong Kong Judges While Trump Runs Wild

【What Say You?】Trump’s “Maduro Grab” Gets a Glossy Spin by the Usual Suspects

【What Say You?】Trump's Judicial Theater: Maduro's Fate Already Sealed

【Deep Throat】Trump's Venezuelan Oil Grab: Big Oil Not Playing Along?

The Most Laughable Lie of the New Year: Jimmy Lai's "Grave Illness" Falls Apart Under Five Hard Facts

【What Say You?】Black Riots “comrades” Thought Ukraine Was Another “Resistance”—Then the Contract Hit

Africa's megacity of Lagos reshapes its coast by dredging and puts environment at risk

- Matthieu Bos Joins Global Critical Resources Corporation as Advisory Board Member

- Energy Leaders Abunayyan Holding and Nextpower Complete Formation of Joint Venture, Nextpower Arabia

- Trump says Iran wants to negotiate as the death toll in protests rises to at least 544

- The Latest: Trump says Iran proposed negotiations as hundreds killed in protests

- Malaysia, Indonesia become first to block Musk’s Grok over sexually explicit AI images

- Hong Kong court hearing arguments on sentencing in former publisher Jimmy Lai's case

- George Floyd and Renee Good: 5 years between Minneapolis videos, and confusion has increased

- UN court to begin hearings on whether Myanmar committed genocide against the Rohingya

- Golden Globe highlights: Brazil on a streak, Amy Poehler's pod wins and Seth Rogen comes full-circle

Film IP fuels expansion of consumer market

- Japanese civil groups oppose restart of Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant

- Chinese yuan strengthens to 7.0108 against USD Monday

- Gold, silver prices surge to record highs on Monday

- US strike hits Venezuelan port, wrecking medical supplies, heritage building

- European leaders condemn US "threatening rhetoric" over Greenland

- Hainan sees booming tourism market following special customs operations launch

- Iranian president vows to engage in dialogue with protesters, but warns against rioters

- Cuban president says ready to defend Cuba, refutes Trump's accusations

- Russia reports strikes on Ukrainian military-industrial sites, Ukraine claims attacks on Russian drilling platforms

CJC Race Launches Global Game-Fi Horse Racing Platform With Real USDT Rewards

- A Symbol of Prosperity to a Hopeful Action -- Reviving Hong Kong's Ocean Heritage

- Celebrate Prosperity and Togetherness at The Ritz-Carlton, Bali

- CES 2026: Roborock releases the world's first robotic vacuum with wheel-leg architecture as it joins hands with Real Madrid Football Club

- World-renowned ice fishing festival kicks off in Hwacheon

- Red lines and increasing self-censorship reshape Hong Kong's once freewheeling press scene

- Railroads and their regulators thwart safety fixes, costing lives

- Crypto News and Data Platform Sandmark Joins Artemis SailGP as Official Partner Ahead of 2026 Season

- Agoda Launches AI-Powered Booking Bot to Help Travelers Book with Confidence

- March Networks Presents New Cloud Storage at Intersec Dubai, Reducing Video Storage Costs by up to 80%

Canadian ice master makes Olympic history with the Games' 1st indoor temporary speedskating rink

- How Olympians think about success and failure and what we can learn from them

- Google teams up with Walmart and other retailers to enable shopping within Gemini AI chatbot

- Erich von Däniken, Swiss writer who spawned alien archaeology, dies at 90

- Germany sharply rejects RFK Jr.'s claims that it prosecutes doctors for vaccine exemptions

- VR headsets are 'hope machines' inside California prisons, offering escape and practical experience

- Doctors say changes to US vaccine recommendations are confusing parents and could harm kids

- Strength training is crucial after menopause. How to make the most of your workouts

- Meta lines up massive supply of nuclear power to energize AI data centers

- From climbing vacuums to cyber pets: Some highlights of CES 2026

Inside the Golden Globes: The reunions and moments the telecast didn't show

- See top photos of stars on the 2026 Golden Globe Awards red carpet

- Celebrities wear pins protesting ICE at the Golden Globes

- The Golden Globes are tonight. Here's what to look for and how to watch and stream the show

- Celebrities embrace black and old Hollywood glamour for Golden Globes red carpet

- Nikki Glaser takes swings at CBS and Leo, goes gentle on Julia in Golden Globes monologue

- The Latest: Golden Globes kicks off Hollywood's 2026 awards season

- Complete list of 2026 Golden Globe Award winners

- Reference to Trump's impeachments is removed from the display of his Smithsonian photo portrait

- Buddhist monks and their dog captivate Americans while walking for peace

Maye throws late TD pass and Patriots' defense roughs up Herbert, Chargers in 16-3 playoff win

- Chargers coach Jim Harbaugh says 'Those that stay will be champions.' QB Justin Herbert isn't sure

- Wolves' Edwards saw Wembanyama switch on him and thought uh-oh, before blowing by him for the winner

- DeMar DeRozan reaches 26,000 career points in Kings' victory over Rockets

- Patriots, 49ers, Bills, Bears and Rams advance to NFL's divisional round

- Josh Allen carries Bills to 27-24 win at Jags for Buffalo's first road playoff victory in 33 years

- Suns breeze past Wizards 112-93 for 10th victory in 13 games

- Alexander-Walker's 24 points lead 6 Hawks in double figures as Atlanta beats Warriors 124-111

- Hertl scores twice in 5-point game, Golden Knights beat Sharks 7-2 for 4th win in a row

- Tim Hardaway Jr. scores 25 points, Aaron Gordon adds 23 and Nuggets beat Bucks 108-104

Hong Kong Marathon 2026: Temporary Road Closures and Transport Adjustments Announced for January 18.

- Three Redhill Peninsula homeowners fined $275,000 for unauthorized building works, court confirms ongoing enforcement actions.

- Greater Bay Area Exhibition Launches to Highlight Opportunities for Hong Kong Youth at Local Universities

- EDB Urges Parents to Participate in Primary One Central Allocation Process for 2026 Admissions

- Hong Kong Marathon and Horse Show Earn M Mark Status for 2026 Events

- Hong Kong's Commitment to Innovation Highlighted at Nobel Heroes Forum

- Applications Open for Enrolled Nurse Training Programme in Welfare Sector Starting 2026-27

- MoneyHero Chief Commercial Officer Views Hong Kong as Most Diversified Market, Eyes Future in Digital Assets

- No New Chikungunya Cases Reported in Hong Kong as Government Enhances Mosquito Control Measures

- Record turnout for Jockey Club Special Marathon to promote social inclusion

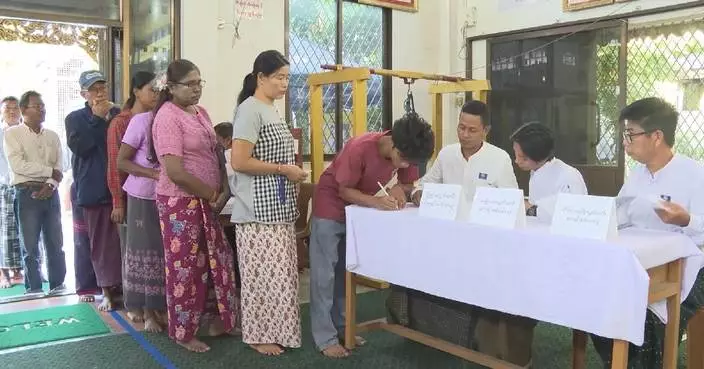

Voting for 2nd phase of Myanmar's general election concludes

- Death toll in Philippine landfill collapse climbs to 8 as rescue efforts continue

- U.S. share of global economy hits lowest point since 1980: Russian media

- BRICS countries kick off joint maritime exercise in South Africa

- Chinese exhibitors present more cooperation opportunities at 2026 CES

- Inner Mongolia section of Yellow River enters stable ice period after 48 days

- Aerial footage records snowy Tianshan Mountains of Xinjiang

- Site in Sichuan wins UN award for outstanding protection of ecological, cultural heritage

- SCO demonstration area in coastal Qingdao reports expanding Europe-bound freight train services in 2025

- China’s ski resorts, ice rinks draw crowds as winter season peaks

Category · News

Canadian ice master makes Olympic history with the Games' 1st indoor temporary speedskating rink

Africa's megacity of Lagos reshapes its coast by dredging and puts environment at risk

Matthieu Bos Joins Global Critical Resources Corporation as Advisory Board Member

Inside the Golden Globes: The reunions and moments the telecast didn't show

CJC Race Launches Global Game-Fi Horse Racing Platform With Real USDT Rewards

Hong Kong Marathon 2026: Temporary Road Closures and Transport Adjustments Announced for January 18.

Energy Leaders Abunayyan Holding and Nextpower Complete Formation of Joint Venture, Nextpower Arabia

Trump says Iran wants to negotiate as the death toll in protests rises to at least 544

The Latest: Trump says Iran proposed negotiations as hundreds killed in protests

Malaysia, Indonesia become first to block Musk’s Grok over sexually explicit AI images

Three Redhill Peninsula homeowners fined $275,000 for unauthorized building works, court confirms ongoing enforcement actions.

Hong Kong court hearing arguments on sentencing in former publisher Jimmy Lai's case

Greater Bay Area Exhibition Launches to Highlight Opportunities for Hong Kong Youth at Local Universities

Film IP fuels expansion of consumer market

A Symbol of Prosperity to a Hopeful Action -- Reviving Hong Kong's Ocean Heritage

Celebrate Prosperity and Togetherness at The Ritz-Carlton, Bali

See top photos of stars on the 2026 Golden Globe Awards red carpet

Japanese civil groups oppose restart of Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant

George Floyd and Renee Good: 5 years between Minneapolis videos, and confusion has increased

Maye throws late TD pass and Patriots' defense roughs up Herbert, Chargers in 16-3 playoff win

Chargers coach Jim Harbaugh says 'Those that stay will be champions.' QB Justin Herbert isn't sure

UN court to begin hearings on whether Myanmar committed genocide against the Rohingya

CES 2026: Roborock releases the world's first robotic vacuum with wheel-leg architecture as it joins hands with Real Madrid Football Club

Chinese yuan strengthens to 7.0108 against USD Monday

Golden Globe highlights: Brazil on a streak, Amy Poehler's pod wins and Seth Rogen comes full-circle

Wolves' Edwards saw Wembanyama switch on him and thought uh-oh, before blowing by him for the winner

ChemWerth Appoints New General Sales Manager To Increase Its Generic API Footprint in India

World-renowned ice fishing festival kicks off in Hwacheon

The top photos of the day by AP's photojournalists

Venezuelans in the US are torn between joy and worry after ousting of Maduro

Celebrities wear pins protesting ICE at the Golden Globes

The Golden Globes are tonight. Here's what to look for and how to watch and stream the show

Red lines and increasing self-censorship reshape Hong Kong's once freewheeling press scene

Railroads and their regulators thwart safety fixes, costing lives

Barbie® Introduces the First Autistic Barbie Doll, Championing Representation for Children through Play

Crypto News and Data Platform Sandmark Joins Artemis SailGP as Official Partner Ahead of 2026 Season

Celebrities embrace black and old Hollywood glamour for Golden Globes red carpet

Nikki Glaser takes swings at CBS and Leo, goes gentle on Julia in Golden Globes monologue

DeMar DeRozan reaches 26,000 career points in Kings' victory over Rockets

The Latest: Golden Globes kicks off Hollywood's 2026 awards season

Complete list of 2026 Golden Globe Award winners

Patriots, 49ers, Bills, Bears and Rams advance to NFL's divisional round

Agoda Launches AI-Powered Booking Bot to Help Travelers Book with Confidence

Josh Allen carries Bills to 27-24 win at Jags for Buffalo's first road playoff victory in 33 years

March Networks Presents New Cloud Storage at Intersec Dubai, Reducing Video Storage Costs by up to 80%

Suns breeze past Wizards 112-93 for 10th victory in 13 games

Alexander-Walker's 24 points lead 6 Hawks in double figures as Atlanta beats Warriors 124-111

Budget Direct Crowned Inaugural Australian 'Insurer of the Year', Leading All Providers With Five Major Wins in the 2026 Finder Awards

Gold, silver prices surge to record highs on Monday

Hertl scores twice in 5-point game, Golden Knights beat Sharks 7-2 for 4th win in a row

Tim Hardaway Jr. scores 25 points, Aaron Gordon adds 23 and Nuggets beat Bucks 108-104

US strike hits Venezuelan port, wrecking medical supplies, heritage building

49ers' George Kittle tears Achilles tendon in playoff win over Eagles

Moritz Wagner returns to Magic ahead of trip home for game in Germany

European leaders condemn US "threatening rhetoric" over Greenland

Purdy, 49ers eliminate defending Super Bowl champion Eagles with 23-19 win in wild-card game

Hainan sees booming tourism market following special customs operations launch

Iranian president vows to engage in dialogue with protesters, but warns against rioters

EDB Urges Parents to Participate in Primary One Central Allocation Process for 2026 Admissions

People rally around the world in support of protests in Iran, in photos

Cuban president says ready to defend Cuba, refutes Trump's accusations

Edwards banks in late go-ahead runner in Timberwolves' 104-103 comeback victory over Spurs

Off the ballot, Ugandan president's son waits in the wings this election

Media OutReach Newswire and Asia News Network (ANN) Form Corporate News Release Partnership

Hong Kong Marathon and Horse Show Earn M Mark Status for 2026 Events

Roman Josi's goal, 2 assists lead Predators over Capitals 3-2

Video captures Minneapolis immigration arrest in a city on edge after shooting of Renee Good

Omdia: Global PC Shipments Grew 9% in 2025 but Memory and Storage Supply Issues Threaten 2026 Outlook

TAT Releases Teaser of "Feel All The Feelings", featuring "LISA" as "Amazing Thailand Ambassador"

Yaber Expands into Smart Cleaning Category with Launch of Two Cordless Vacuum Cleaners

SL Aesthetic Group Celebrates 22 Years of Growth and Innovation Across Singapore and Southeast Asia

Trump's motorcade in Florida rerouted due to 'suspicious object'

Hong Kong's Commitment to Innovation Highlighted at Nobel Heroes Forum

Scottie Barnes hits tiebreaking free throw in final second of OT as Raptors beat 76ers 116-115

Agoda Data Shows Vietnam Rising as a Favorite End-of-Year Destination for Families Across Asia and Beyond

FPT Software Positioned as a Leader in IDC MarketScape Report for AI-Enabled Front Office Conversational AI Software in Asia-Pacific

Nattakorn Wattanaumphaipong Joins Great American Insurance Company’s Singapore Branch

Trump 'inclined' to keep ExxonMobil out of Venezuela after CEO response at White House meeting

Russia reports strikes on Ukrainian military-industrial sites, Ukraine claims attacks on Russian drilling platforms

How to watch the 2026 Australian Open on TV, the schedule, seedings and more

Voting for 2nd phase of Myanmar's general election concludes

Death toll in Philippine landfill collapse climbs to 8 as rescue efforts continue

A New Era of Digital Innovation: Elitery Global Technology Sdn. Bhd. Granted Malaysia Digital (MD) Status

Applications Open for Enrolled Nurse Training Programme in Welfare Sector Starting 2026-27