BOSTON (AP) — Harvard University has decided against removing from campus buildings the name of a family whose company makes the powerful painkiller OxyContin, despite protests from parents whose children fatally overdosed.

The decision last month by the Harvard Corporation to retain Arthur M. Sackler's name on a museum building and second building runs counter to the trend among several institutions around the world that have removed the Sackler name in recent years.

Among the first to do it was Tufts University, which in 2019 announced that it would remove the Sackler name from all programs and facilities on its Boston health sciences campus. The Louvre Museum in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York have also removed the Sackler name. Signage at London's Tate Modern and Tate Britain as well as New York’s Guggenheim Museum has also been removed.

The move by Harvard, which was confirmed Thursday, was greeted with anger from those who had pushed for the name change as well as groups like the anti-opioid group Prescription Addiction Intervention Now or P.A.I.N. It was started by photographer Nan Goldin, who was addicted to OxyContin from 2014 to 2017, and the group has held scores of museum protests over the Sackler name.

“Harvard’s continued embrace of the Sackler name is an insult to overdose victims and their families,” P.A.I.N. said in a statement Friday. “It’s time that Harvard stand by their students and live up to their mandate of being a repository of higher learning of history and an institution that embodies the best of human values.”

Mika Simoncelli, a Harvard graduate who organized a student protest over the name in 2023 with members of P.A.I.N, called the decision “shameful.”

“Even after a receiving a strong, thorough proposal for denaming, and facing multiple protests from students and community members about Sackler name, Harvard lacks the moral clarity to make a change that should have been made years ago," they said in an email interview Friday. “Do they really think they’re better than the Louvre?”

OxyContin first hit the market in 1996, and Purdue Pharma’s aggressive marketing of it is often cited as a catalyst of the nationwide opioid epidemic, with doctors persuaded to prescribe painkillers with less regard for addiction dangers.

The drug and the Stamford, Connecticut-based company became synonymous with the crisis, even though the majority of pills being prescribed and used were generic drugs. Opioid-related overdose deaths have continued to climb, hitting 80,000 in recent years. Most of those are from fentanyl and other synthetic drugs.

In making its decision, the Harvard report raised doubts about Arthur Sackler's connection to OxyContin, since he died nine years before the painkiller was introduced. It called his legacy “complex, ambiguous and debatable.”

The proposal was put forth in 2022 by a campus group, Harvard College Overdose Prevention and Education Students. The university said it would not comment beyond what was in the report.

“The committee was not persuaded by the argument that culpability for promotional abuses that fueled the opioid epidemic rests with anyone other than those who promoted opioids abusively,” the report said.

“There is no certainty that he would have marketed OxyContin — knowing it to be fatally addictive on a vast scale — with the same aggressive techniques that he employed to market other drugs,” it continued. “The committee was not prepared to accept the general principle that an innovator is necessarily culpable when their innovation, developed in a particular time and context, is later misused by others in ways that may not have been foreseen originally.”

A spokesperson for Arthur Sackler's family did not respond to a request for comment.

In June, the Supreme Court rejected a nationwide settlement with OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma that would have shielded members of the Sackler family from civil lawsuits over the toll of opioids but also would have provided billions of dollars to combat the opioid epidemic.

The Sacklers would have contributed up to $6 billion and given up ownership of the company but retained billions more. The agreement provided that the company would emerge from bankruptcy as a different entity, with its profits used for treatment and prevention. Mediation is underway to try to reach a new deal; if there isn't one struck, family members could face lawsuits.

FILE - Kathleen Scarpone, of Kingston, N.H., protests in front of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum at Harvard University, Friday, April 12, 2019, in Cambridge, Mass. (AP Photo/Josh Reynolds)

MILAN--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Apr 5, 2025--

REJO, a global provider of heat-not-burn(HNB) solutions, proudly unveils its refreshed brand identity and strategic expansion into the European market, which is a meaningful milestone in its journey of growth and innovation. Known for crafting innovative and reliable products, REJO’s new visual identity reflects its progressive approach to advancing the industry.

This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20250404882478/en/

Strategic Market Entry into Europe

Building on its steady progress in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, REJO is now poised to tackle the challenges of the European market with a focus on Switzerland and the Czech Republic with its diverse product range and market adaptability. Recognizing the rising demand for herbal alternatives, REJO is making thoughtful investments in heat-not-burn products, including TOZE herbal sticks, inspired by East Asia’s rich tradition of tea-based cigarettes.

Designed to deliver a refined user experience, TOZE herbal sticks pair seamlessly with REJO HS40, the company’s signature heating device, ensuring optimal flavor and consistency. This tailored approach positions REJO as a reliable provider of innovative alternatives in European HNB market.

A Fresh Look for a New Chapter

“Take a Break. Take REJO.”

With a renewed vision, REJO unveils a refreshed brand identity alongside a new slogan that underscores its commitment to offering innovative alternatives to traditional smoking. The brand now features a vibrant color palette, centered around a warm, inviting shade of green-symbolizing comfort, relaxation and a natural connection to the essence of the product.

The redesigned brand icon, featuring an extended “O” with a petal-like shape, highlights REJO’s advanced heating technology and reflects the brand’s commitment to innovation. This change aligns with REJO’s mission to empower individuals with mindful alternatives that redefine the smoking experience, while embracing the smoke-free future alongside its global partners.

REJO aims to be a trusted companion during those brief five-minute pauses in life, offering a diverse range of alternatives that support the journey toward a mindful lifestyle. Through ongoing innovation, REJO is driving change and inspiring an elevated way of living for consumers around the world.

Commitment to Innovation

The TOZE brand name embodies REJO’s commitment to join a smoke-free future, symbolizing the combination of “TO-bacco ZE-ro”.

Leveraging the well-established expertise in tea-based cigarettes from East Asia, REJO has innovated a unique herbal stick formulation that combines natural tea fibers, nicotine, and precisely balanced flavors. After over 300 product trials, REJO has perfected a formula that enhances aroma absorption while delivering a rich, full-bodied experience with every use.

Paired with the REJO HS40 heating device-boasting an impressive 40-stick capacity per charge-this combination delivers a smoother, more consistent flavor profile.

Strengthening Market Presence in Europe

REJO is strengthening its foothold in Europe, starting with the Czech Republic and Switzerland. Following a recently signed Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with a Czech distributor, REJO is poised to further expand TOZE’s footprint across the region. This initiative is part of a broader market strategy to establish a strong European presence.

Early market feedback from France, particularly among traditional tobacco retailers, has underscored the growing demand for TOZE products. Praised for their consistent aroma and reduced smoke odor, TOZE herbal sticks are well-positioned to meet the rising market demand for flavored alternatives.

Localized Growth and Consumer Engagement

REJO’s European expansion goes beyond product availability-it’s about building lasting connections with consumers. The company is actively recruiting industry professionals who embody its brand spirits:

“Stay Courageous, Be Undefined.”

To ensure a seamless market entry, REJO has secured key regulatory approvals, including: Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) registration, Poison Centre Notification (PCN) compliance, and Track-and-Trace registration.

Additionally, REJO is launching the REJO Club Fans Community, blending online interactions with offline events to create meaningful brand experiences and foster deeper connections with local users. By redefining the traditional five-minute break, REJO seeks to engage consumers through interactive experiences that go beyond product use, exploring new possibilities while meeting consumer needs.

Global Expansion and Continued Growth

While Europe remains a key focus, REJO continues to expand its global footprint, with products now available in nearly 10,000 retail outlets across Russia, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. With a diversified product portfolio and the flexibility to adapt to various markets, REJO is poised for continued growth.

In Southeast Asia, REJO has rapidly expanded its presence, securing distribution in convenience stores and lifestyle locations. In Indonesia, the brand has established brand booths in cafés and dining bars, integrating e-commerce solutions for greater accessibility.

In the Middle East, REJO has solidified its presence through an exclusive partnership agreement at World Tobacco Dubai 2024 and a major distributor event in Dubai, engaging over 20 secondary distributors.

These efforts reflect REJO’s commitment to scalable, sustainable growth in key markets worldwide.

Pioneering the Future of Heat-Not-Burn Solutions

As REJO continues its global expansion, the company remains committed to its mission of redefining the smoking experience through innovation, reliability, and sustainability. With a strong foundation in place and ambitious plans for growth in Europe and beyond, REJO is committed to delivering reliable alternatives that empower consumers to make informed choices about their smoking experience.

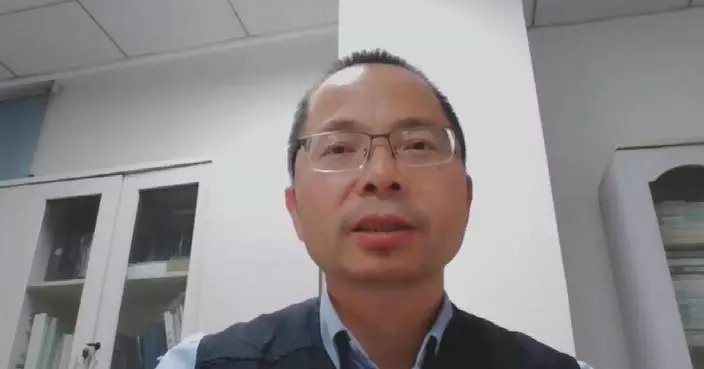

“We remain flexibility in adapting to the changing market. By integrating market insights with technological advancements, we are confident that our European expansion will strengthen our position within the HNB industry,” said Li. “We believe in the potential of this market and are dedicated to creating reliable, accessible alternatives that cater to the evolving needs of global consumers.”

About REJO

REJO is a pioneering global provider in heat-not-burn solutions, crafting innovative and reliable products that redefine the smoking experience.

In partnership with REJO Friends, we are committed to delivering exceptional user experiences worldwide. Our diverse product portfolio champions healthier alternatives, setting a new standard for mindful consumption.

For more information about REJO and its products, visit www.rejonow.com.

Loic Li, Global Sales Director, Shares His Confidence in Expanding REJO’s Presence in the European Market

Crowds Gathering at the REJO Stand