Feature · News

BP China Insight : U.S. Negotiates with Iran While Suddenly Launching War

Green waste incineration plant in south China's Shenzhen turns trash into energy, resources

Measures adopted to ensure smooth return trips after Spring Festival holidays in China

UN calls for returning to negotiating table as U.S., Israel intensify attacks on Iran

US-Israeli strikes against Iran amid negotiations "shocking": Chinese envoy

What to know about the latest US-Israeli attacks on Iran

China's film market soars past 10 bln yuan, driving economic boom, cultural tourism

BP China Insight : China's Lunar Landing Support Facilities Announced – NASA Scrambles to Revise Timeline

Chinese shares close mixed Friday amid PBOC cuts FX risk reserve ratio

Chinese FM holds phone talks with Russian counterpart over US-Israeli strikes on Iran

Labour Department to Offer Free Occupational Safety Training Courses from April to June 2026

Gaza's ceasefire had some momentum. Now, some fear a new war will distract the world

Photos show US-Israeli strikes and Iran's response

Government Launches Hotline for Wang Fuk Court Housing Arrangements Starting Today

3 US troops killed and 5 are seriously wounded during Iran attacks, military says

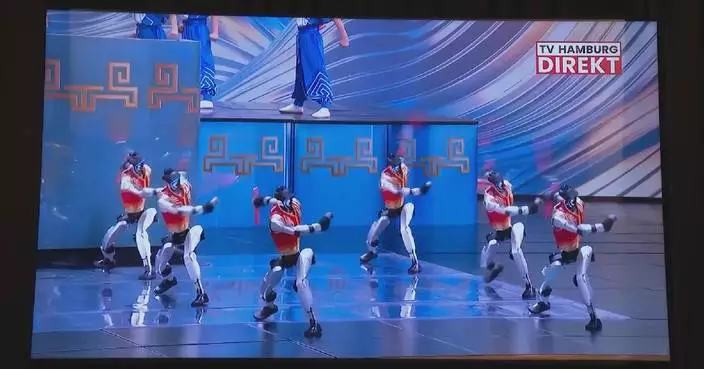

International version of China's Spring Festival Gala aired in Germany

China's film market soars past 10 bln yuan, driving economic boom, cultural tourism

BP China Insight : China's Lunar Landing Support Facilities Announced – NASA Scrambles to Revise Timeline

Chinese shares close mixed Friday amid PBOC cuts FX risk reserve ratio

Chinese FM holds phone talks with Russian counterpart over US-Israeli strikes on Iran

BP China Insight : U.S. Negotiates with Iran While Suddenly Launching War

Green waste incineration plant in south China's Shenzhen turns trash into energy, resources

Measures adopted to ensure smooth return trips after Spring Festival holidays in China

UN calls for returning to negotiating table as U.S., Israel intensify attacks on Iran

US-Israeli strikes against Iran amid negotiations "shocking": Chinese envoy

What to know about the latest US-Israeli attacks on Iran

Labour Department to Offer Free Occupational Safety Training Courses from April to June 2026

Gaza's ceasefire had some momentum. Now, some fear a new war will distract the world

Photos show US-Israeli strikes and Iran's response

Government Launches Hotline for Wang Fuk Court Housing Arrangements Starting Today

3 US troops killed and 5 are seriously wounded during Iran attacks, military says

International version of China's Spring Festival Gala aired in Germany

Feature·Bloggers

War widens to include Iranian-backed militias as Israeli and American planes pound Iran

- Photos show Lebanese people fleeing after Israeli strikes

- Iran's nuclear ambassador alleges that US-Israeli airstrikes targeted the Natanz enrichment facility

- The Latest: Iranian-backed militias join fight as war on Iran widens

- Where things stand after the US and Israeli strikes on Iran

- Pakistan deploys troops, imposes 3-day curfew after deadly protests over US-Israeli strikes on Iran

- India and Canada agree to boost economic partnership in a move to reset ties

- Myanmar's military government pardons 10,000 prisoners before parliament opens

- Oil prices rise sharply after attacks in Middle East disrupt global energy supply

- Photos show Israel after Iran retaliated with missiles

Hong Kong stocks close 2.14 pct lower

- Chinese shares close mixed Monday

- Traditional Nine-Turn Lantern Fair celebrated in Shanxi

- 3,000-strong folk parade celebrates Lantern Festival in China's Qinghai

- Singaporean expert urges West to embrace China's solution to global governance

- Protests burst out in Baghdad against US-Israeli strikes on Iran

- Iran not to negotiate with US: security chief

- Air raid sirens, explosions rock Jerusalem as Iran launches new attacks

- China opposes British sanctions on Chinese firms under "Russia-related" pretext

- Yiwu exporters seek ways to mitigate disruptions of Iran tensions

MEXC Launches Commodity Zero-Fee Gala with $1 Million in Trading Rewards

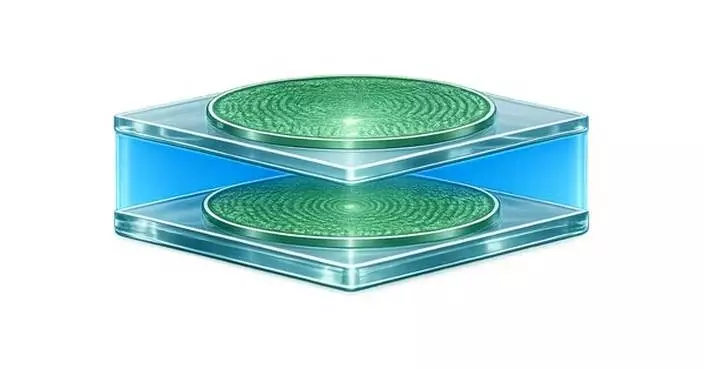

- Development collaboration update: Compact Tunable Metalens Module Advances 3D Non-Contact Fingerprint Biometrics Toward Smartphone Integration Possibilities

- Shrewsbury International School Hong Kong Launches Key Stage 3, Establishing Seamless Pathways to Global Excellence

- KuCoin Enhances Lite Mode With Earn and Feed, Supporting Confident Entry Into Crypto and Broader Adoption

- “AI Realized Through Display” … Samsung Display Showcases AI-Optimized OLED Technologies at MWC26

- RHI Magnesita 2025 Full Year Results: Disciplined Execution and Strong H2 Performance Deliver Resilient Earnings in Challenging Market Environment

- TECNO Expands AI Ecosystem at MWC 2026, Forging the "Connection of Intelligence"

- Hisense Leads Global TV Shipments in 2025 Across 100-Inch+ and Laser TVs

- Shangpu Group Issues Market Position Statement Recognizing SALIAI's Patented Cellular Essence Global Pioneer

- pureLiFi Debuts 10 Gbps "Connectivity DNA" and Bridges the 5G Gap With Global FWA Partners at MWC

Research Finds AI’s Energy Use Is Driving Concern

- Accessible walks bring the joys of birding to people with mobility and other limitations

- Electrolyte supplements are everywhere. Who benefits from them and when?

- OpenAI gets $110 billion in funding from a trio of tech powerhouses, led by Amazon

- Callers to Washington state hotline press 2 for Spanish and get accented AI English instead

- NASA revamps Artemis moon landing program by modeling it after speedy Apollo

- One Tech Tip: Unspoken group chat rules you're probably ignoring, but shouldn't

- New sleeping sickness pill gets nod, paving the way for use in Africa

- Growing more complex by the day: How should journalists govern use of AI in their products?

- A total lunar eclipse will turn the moon blood red on Tuesday across several continents

See top photos of stars on the 2026 Actor Awards red carpet and show

- Q&A: K-pop girl group Twice exploded in the last decade. Then 'KPop Demon Hunters' came calling

- Catherine O'Hara wins posthumous award for 'The Studio' at Actor Awards

- Updated list of winners at the 2026 Actor Awards

- Catherine O'Hara wins posthumous award for 'The Studio' at Actor Awards

- 'Scream 7' opens with a franchise-best $64.1 million in box-office win for Paramount

- Silvana Armani honors a fashion dynasty with fluid, essential collection during Milan Fashion Week

- 'One Battle After Another' wins at PGA Awards, setting up awards-season sweep

- See photos from the NAACP Image Awards, a celebration of Black excellence in arts and culture

- Viola Davis receives prestigious Chairman's prize at NAACP Image Awards

Luka and LeBron lead Lakers past Kings 128-104 to complete back-to-back weekend wins

- Gauthier scores 2 goals and Ducks edge Flames 3-2 in shootout for 8th straight home win

- Clippers beat the Pelicans 137-117 to end a 3-game losing streak

- Gilgeous-Alexander scores 30 points to lead the Thunder past the Mavericks, 100-87

- Queta's career-high 27 points spark Celtics to 114-98 win over 76ers

- Juventus boosts Champions League hopes with stoppage-time equalizer at Roma

- Lionel Messi, Telasco Segovia rally Inter Miami to 4-2 victory over Orlando City

- Azzi Fudd helps No. 1 UConn rout St. John's 85-49 for 47th consecutive victory

- James Harden helps Cavs to a road win while playing with a broken thumb

- Cunningham, Harris help NBA-leading Pistons beat Magic for 6th straight road victory

Hong Kong Announces Global Talent Summit Week to Enhance International Collaboration and Opportunities

- Hong Kong Awards Sandy Ridge Data Facility Cluster to Boost AI and Computing Power Development

- Cholera Cases Prompt Health Officials to Urge Public on Water System Safety and Precautions

- Hong Kong Showcases Culture and Energy at Sydney Lunar New Year Dragon Boat Festival

- Man Sentenced to Two Months for Illegally Importing 32,000 Tobacco Heat Sticks into Hong Kong

- Hong Kong Diamond Show: Customs Enforces Regulations for Precious Metals and Stones Dealers

- Hong Kong and Shanghai Sign MOU to Enhance Digital Cargo Trade and Finance Cooperation

- Chief Executive John Lee Heads to Beijing for National People's Congress, Returns March 5

- Hong Kong Signs Double Taxation Agreement with Kyrgyz Republic to Boost Trade and Investment

- LCSD Launches Best Landscape Award 2026 with New Subsidised Sale Housing Category; Nominations Open Until May 18

Labor unions, civic groups stage anti-war demonstrations in Greece

- Massive demonstration against U.S.-Israel strikes on Iran staged in Amsterdam

- Trump seeks to avoid prolonged war with Iran: former US diplomat

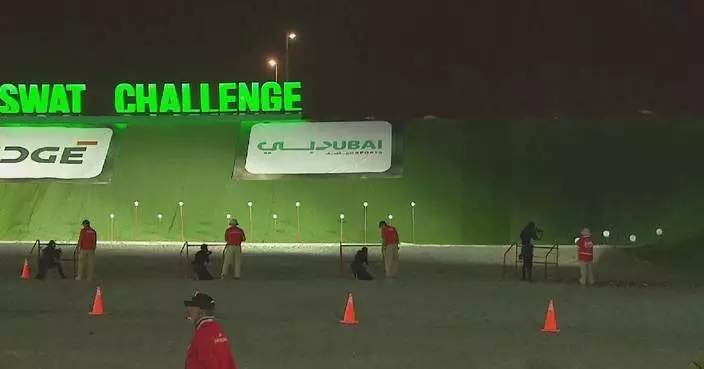

- Fresh huge explosions hit Dubai as Iran keeps up strikes on U.S. military targets

- Iran launches second day of attacks on US military base in Qatar

- Japanese scholar voices concern over constitutional revision moves

- Russia reports strikes on Ukrainian energy facilities, Ukraine claims hits on Russian military concentrations

- Oil prices surge amid Middle East tensions

- Trump says Iran operation could last 4 weeks as Tehran intensifies counterattacks

- Locals in ROK rally against joint US military drills, Trump tariffs

Category · News

War widens to include Iranian-backed militias as Israeli and American planes pound Iran

Photos show Lebanese people fleeing after Israeli strikes

Iran's nuclear ambassador alleges that US-Israeli airstrikes targeted the Natanz enrichment facility

The Latest: Iranian-backed militias join fight as war on Iran widens

MEXC Launches Commodity Zero-Fee Gala with $1 Million in Trading Rewards

Where things stand after the US and Israeli strikes on Iran

Development collaboration update: Compact Tunable Metalens Module Advances 3D Non-Contact Fingerprint Biometrics Toward Smartphone Integration Possibilities

Pakistan deploys troops, imposes 3-day curfew after deadly protests over US-Israeli strikes on Iran

Shrewsbury International School Hong Kong Launches Key Stage 3, Establishing Seamless Pathways to Global Excellence

KuCoin Enhances Lite Mode With Earn and Feed, Supporting Confident Entry Into Crypto and Broader Adoption

“AI Realized Through Display” … Samsung Display Showcases AI-Optimized OLED Technologies at MWC26

Hong Kong Announces Global Talent Summit Week to Enhance International Collaboration and Opportunities

Hong Kong stocks close 2.14 pct lower

Hong Kong Awards Sandy Ridge Data Facility Cluster to Boost AI and Computing Power Development

Chinese shares close mixed Monday

RHI Magnesita 2025 Full Year Results: Disciplined Execution and Strong H2 Performance Deliver Resilient Earnings in Challenging Market Environment

Cholera Cases Prompt Health Officials to Urge Public on Water System Safety and Precautions

Labor unions, civic groups stage anti-war demonstrations in Greece

Traditional Nine-Turn Lantern Fair celebrated in Shanxi

Massive demonstration against U.S.-Israel strikes on Iran staged in Amsterdam

3,000-strong folk parade celebrates Lantern Festival in China's Qinghai

TECNO Expands AI Ecosystem at MWC 2026, Forging the "Connection of Intelligence"

Hisense Leads Global TV Shipments in 2025 Across 100-Inch+ and Laser TVs

Singaporean expert urges West to embrace China's solution to global governance

Hong Kong Showcases Culture and Energy at Sydney Lunar New Year Dragon Boat Festival

India and Canada agree to boost economic partnership in a move to reset ties

See top photos of stars on the 2026 Actor Awards red carpet and show

Man Sentenced to Two Months for Illegally Importing 32,000 Tobacco Heat Sticks into Hong Kong

Hong Kong Diamond Show: Customs Enforces Regulations for Precious Metals and Stones Dealers

Shangpu Group Issues Market Position Statement Recognizing SALIAI's Patented Cellular Essence Global Pioneer

pureLiFi Debuts 10 Gbps "Connectivity DNA" and Bridges the 5G Gap With Global FWA Partners at MWC

Myanmar's military government pardons 10,000 prisoners before parliament opens

Medimaps Group and Radiobotics Announce Strategic Merger to Expand AI-Driven Musculoskeletal Imaging Portfolio

Setting the benchmark in sustainable comminution: Metso and Loesche introduce transformative dry grinding technology

vivo Unveils Flagship X300 Ultra at MWC 2026: Showcasing Pioneering 400mm Equivalent vivo ZEISS Telephoto Extender Gen 2 Ultra and Announcing Global Availability

Trump seeks to avoid prolonged war with Iran: former US diplomat

Oil prices rise sharply after attacks in Middle East disrupt global energy supply

Protests burst out in Baghdad against US-Israeli strikes on Iran

Photos show Israel after Iran retaliated with missiles

FBI investigates Texas bar shooting that killed 2 and wounded 14 as possible terrorist act

HARMAN and Viasat Collaborate to Enable In-Cabin Voice Calls Over Satellite Communications

HARMAN Announces Ready Ride: A Rugged, Scalable Connectivity Platform Built for the Future of Two-Wheeled Mobility

Qualcomm and Other Industry Leaders Commit to 6G Trajectory Towards Commercialization Starting from 2029 Onwards

Mantle and Aave Cross $1 Billion in Total Market Size in Under Three Weeks, as DeFi TVL Hits All-Time High

Iran not to negotiate with US: security chief

The Last SIM Card Businesses Will Ever Need - emnify Introduces a Programmable SGP.32 Connectivity Model

Research Finds AI’s Energy Use Is Driving Concern

Thales sets a world first in quantum-safe security for 5G networks

Samji Electronics Selects MaxLinear’s Sierra Single-Chip Radio for High-Performance Macro O-RU

Quectel Showcases Advanced mmWave Radar Solutions for Smarter, Safer Vehicles at MWC Barcelona

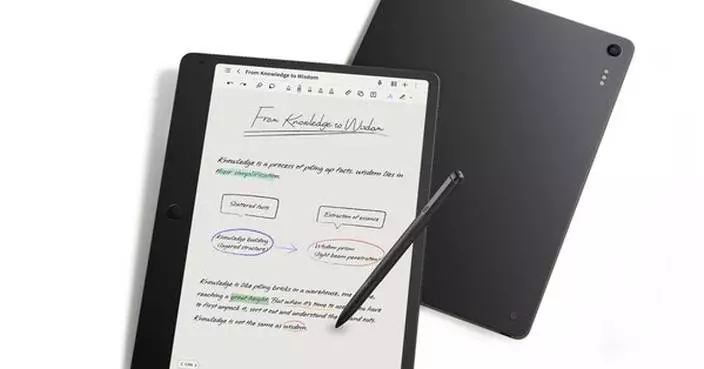

TCL Unveils New Tablet Lineup at MWC 2026

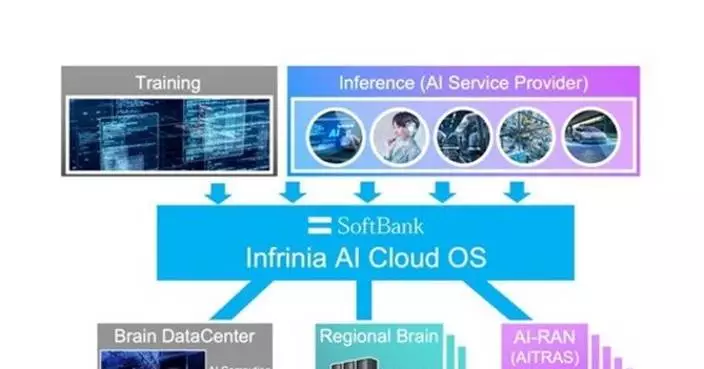

SoftBank Corp. Announces Telco AI Cloud Vision to Build Social Infrastructure for the AI Era, Leveraging Its Telecommunications Foundation

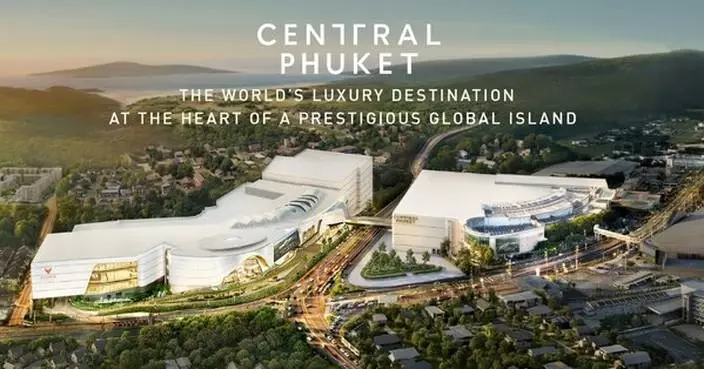

Central Phuket Unveils US$836 Million Expansion to Drive Phuket's Transformation into a Global Luxury Living and Investment Hub

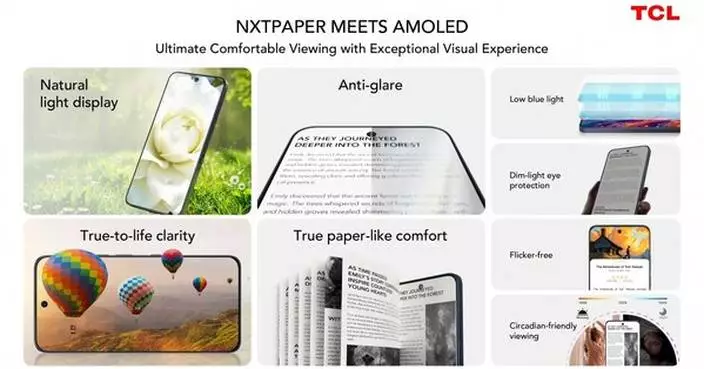

TCL Unveils Next-Generation NXTPAPER Technology on AMOLED, Redefining Visual Comfort and Mobile Display Excellence

TCL Showcases TCL NXTPAPER 70 Pro at MWC 2026, Bringing Holistic All-Day Eye Comfort to Modern Mobile Life

TCL Unveils New TCL CrystalClip Open-Ear Earbuds, with Special Edition Featuring Crystals by Swarovski®

Supermicro Expands Support for AI-RAN and Sovereign AI Solutions to Deliver High-Performance, Efficient, and Scalable AI Infrastructure

Fresh huge explosions hit Dubai as Iran keeps up strikes on U.S. military targets

Air raid sirens, explosions rock Jerusalem as Iran launches new attacks

Iran launches second day of attacks on US military base in Qatar

CIFF Guangzhou 2026: CIFM/interzum guangzhou 2026 to Connect Global Supply Chains

Hong Kong and Shanghai Sign MOU to Enhance Digital Cargo Trade and Finance Cooperation

The Wynn Signature Chinese Wine Awards Judging Week Returns for a Third Consecutive Year in March

COLUMBIA ASIA HOSPITAL BUKIT JALIL LAUNCHES NEW CATH LAB TO STRENGTHEN HEART CARE SERVICES

17 Years of PT SMI: Strengthening Transformation as a DFI and a Catalyst for National Development

Bidgely to Showcase AI-Powered Energy Intelligence at IDC European Utilities Xchange

NTT DOCOMO, StarHub, and ServiceNow keep travelers connected with autonomous roaming resolution using ServiceNow CRM

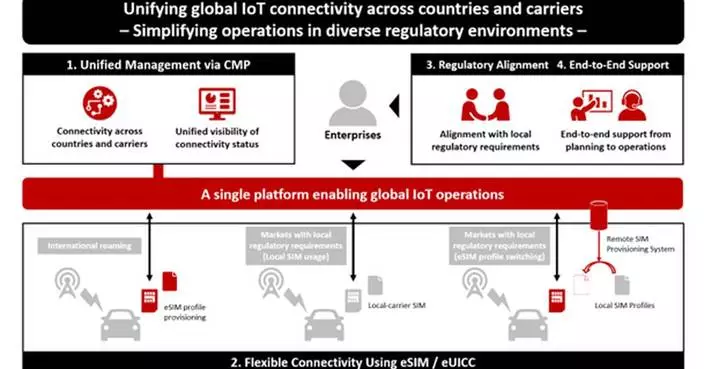

NTT DOCOMO BUSINESS and Airlinq Form Strategic Partnership for Global IoT

Chief Executive John Lee Heads to Beijing for National People's Congress, Returns March 5

China opposes British sanctions on Chinese firms under "Russia-related" pretext

Yiwu exporters seek ways to mitigate disruptions of Iran tensions

Hong Kong Signs Double Taxation Agreement with Kyrgyz Republic to Boost Trade and Investment

Japanese scholar voices concern over constitutional revision moves

Chinese yuan weakens to 6.9236 against USD Monday

Russia reports strikes on Ukrainian energy facilities, Ukraine claims hits on Russian military concentrations

Blow after blow to the power of Iran and its proxy militias set the stage for US-Israel attacks

As Macron sets out his nuclear doctrine, a look at France's capability by the numbers

PHCbi Launches LiCellGrow™ Cell Expansion System to Support High-Quality and Efficient Production of Cell and Gene Therapies

Q&A: K-pop girl group Twice exploded in the last decade. Then 'KPop Demon Hunters' came calling

Rev. Jesse Jackson returns home to South Carolina to lie in state

Corning Launches Corning® Gorilla® Glass Ceramic 3 with Enhanced Drop Durability

OXIO Survey: Mobile Loyalty Is Up for Grabs as Switching Gets Easier and Gen Z Reshapes the Market

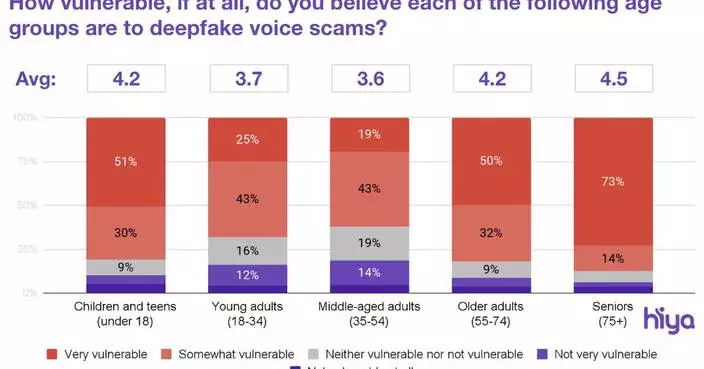

State of the Call 2026: AI Deepfake Voice Calls Hit 1 in 4 Americans as Consumers Say Scammers Are Beating Mobile Network Operators 2-to-1

Aurzen Brings Pocket-Sized Projection and Immersive Audio to MWC 2026