Feature · News

China's aggregate social financing maintains high growth in 2025

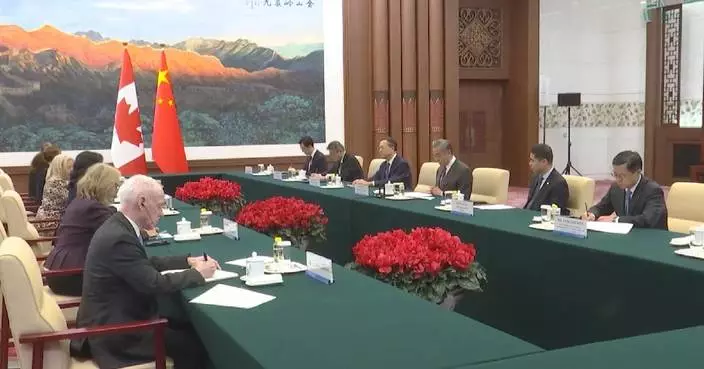

China ready to work for steady, sound ties with Canada: FM

Venezuelan workers rally for Maduro's return

Canadian PM's visit to China paves way for more pragmatic trade ties: scholar

"Soft landing" of China-EU EV case to significantly boost market confidence: MOC spokeswoman

Iranian security forces disperse anti-government demonstrators

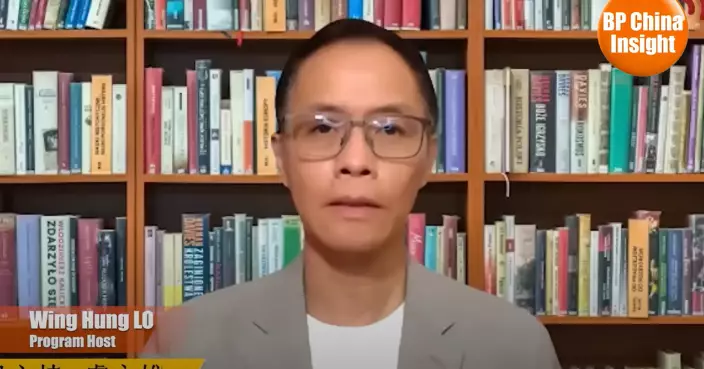

BP China Insight: US power shortage: considering using aircraft carrier to generate electricity

Clayton Kershaw not quite done pitching, will play for US in World Baseball Classic

China's foreign trade promises further growth in 2026

China ready to work for steady, sound ties with Canada: FM

Explosion damages homes and injures at least 4 in the Netherlands

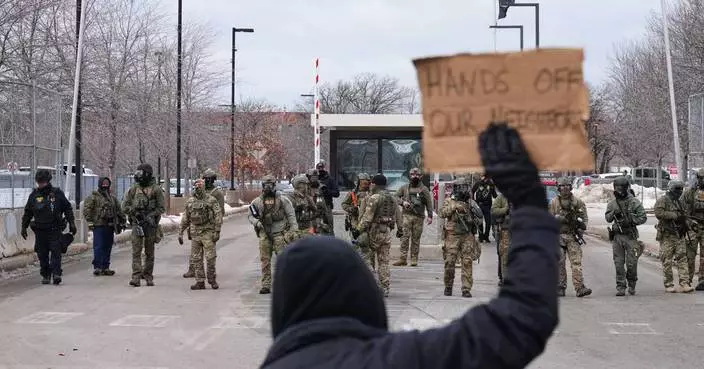

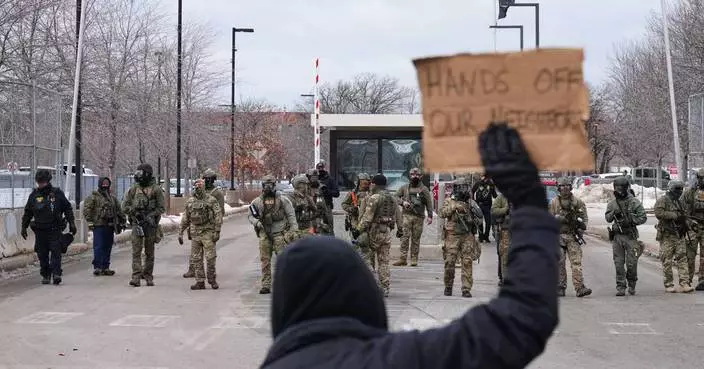

Photos of tensions between federal officers and locals in Minneapolis

Delays plague voting in Uganda's presidential election

Photos show Ukrainians enduring a frigid winter after Russian strikes knocked out power

Proposals on immigration enforcement flood into state legislatures, heightened by Minnesota action

Senators launch a cross-party effort to end stock trading by lawmakers

BP China Insight: US power shortage: considering using aircraft carrier to generate electricity

Clayton Kershaw not quite done pitching, will play for US in World Baseball Classic

China's foreign trade promises further growth in 2026

China ready to work for steady, sound ties with Canada: FM

China's aggregate social financing maintains high growth in 2025

China ready to work for steady, sound ties with Canada: FM

Venezuelan workers rally for Maduro's return

Canadian PM's visit to China paves way for more pragmatic trade ties: scholar

"Soft landing" of China-EU EV case to significantly boost market confidence: MOC spokeswoman

Iranian security forces disperse anti-government demonstrators

Explosion damages homes and injures at least 4 in the Netherlands

Photos of tensions between federal officers and locals in Minneapolis

Delays plague voting in Uganda's presidential election

Photos show Ukrainians enduring a frigid winter after Russian strikes knocked out power

Proposals on immigration enforcement flood into state legislatures, heightened by Minnesota action

Senators launch a cross-party effort to end stock trading by lawmakers

Feature·Bloggers

【Deep Throat】Trump's Latest Iran Tariff Bluff: China Sees Right Through It

【Ariel】Jimmy Lai’s “Solitary” Twist: Judges Say He Asked For It

【What Say You?】Accomplice Witness Chen Zihao: Family Stalked, Fears Black Bloc Revenge After Release

【Deep Blue】International Laws? You Kidding Me?

【Bastille Commentary】Chicken-hearted Conservatives: Sanctioning Hong Kong Judges While Trump Runs Wild

【What Say You?】Trump’s “Maduro Grab” Gets a Glossy Spin by the Usual Suspects

Inside a year of firings that have shaken the Trump Justice Department: 'A great deal of fear'

- Inside a year of firings that have shaken the Trump Justice Department: 'A great deal of fear'

- Trump isn't waiting for future generations to name things after him. It's happening now

- Judge orders release of Liberian man arrested in Minneapolis by agents with a battering ram

- Fire breaks out in Seoul's last-remaining shanty town

- Middle East allies in blitz of diplomacy urged Trump to hold off on Iran strikes, diplomat says

- Venezuela's Machado says she presented her Nobel Peace Prize to Trump during their meeting

- Fantôme Rapport Launches in English — A Romance, Horror, and Mystery Adventure Aboard a Ghostly Luxury Liner

- Trump threatens to use the Insurrection Act to end protests in Minneapolis

- The Latest: UN Security Council discusses Iran's deadly protests after US request

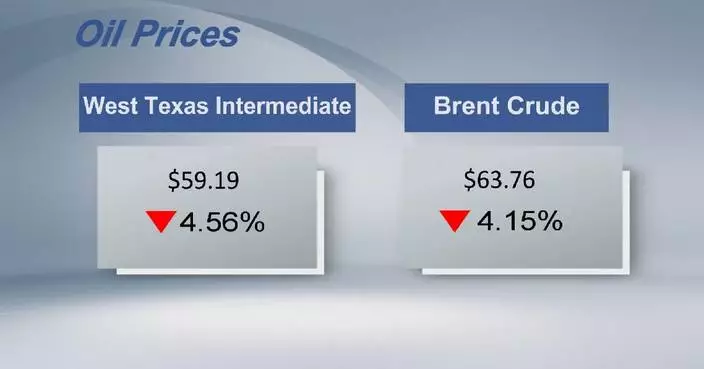

Crude futures settle lower

- China to expand high-standard opening-up to foster win-win cooperation: minister

- BMO China president highlights growth opportunities in Canada-China trade

- Xi to meet Canadian PM

- China calls for restraint at UNSC meeting on Iran situation

- China's commercial rocket launches new satellites from sea

- Former Taiwan TV host bridges cross-Strait divide via online media

- Chinese, Iranian FMs have phone conversation

- China's top legislator meets Canadian PM

- China willing to strengthen cooperation with Canada: premier

Kerry Launches 2026 Supplements Taste Charts: Defining the Next Era of Flavour in Supplements and Sports Nutrition

- Coda and Unity to enable out-of-app monetization for game developers globally

- NSF Launches Retail Food Safety Audits Program in ASEAN and Australia

- CIOs Face an Accelerating Gap as Adaptive IT Leadership in the Spotlight at Info-Tech LIVE 2026 in Brisbane

- Chow Tai Fook Jewellery Launches Next Phase of International Expansion with New Bangkok Opening and Appointment of Global Brand Ambassador

- Harnessing the Power of Sports: Orange Lion Sports Leads the Way in Driving the Emerging Trend of "Racecation"

- Dreame Debuts AI-Powered Whole-home Smart Ecosystem at CES 2026, Earning Multiple Industry Awards

- Infobip strengthens leadership to drive growth and innovation

- GIGABYTE Showcases Practical AI TOP Utility for Local AI Applications at CES 2026

- TVBS and Disney+ Achieve Record-Breaking Success with 40th Golden Disc Awards in Taiwan

How the White House and governors want to fix AI-driven power shortages and price spikes

- What you need to know about Grok and the controversies surrounding it

- At Detroit auto show, spotlight dims for EVs

- What to know about UK legal changes aiming to regulate AI-generated nude images

- Ailing astronaut returns to Earth early in NASA's first medical evacuation

- Aimed at the growing number of young Chinese who live alone, a new app asks: ‘Are you dead?'

- Wikipedia unveils new AI licensing deals as it marks 25th birthday

- Grok blocked from undressing images in places where it's illegal, X says

- NASA sends 4 astronauts back to Earth in first medical evacuation

- Public mistrust linked to drop in deceased donor organ donations and kidney transplants

Kathleen Kennedy, steward of 'Star Wars,' steps down from Lucasfilm

- Former Universal chair David Linde named CEO of Sundance Institute

- The new BTS album title and what to know about the K-pop band’s comeback

- Min Jin Lee's 'Pachinko' follow-up, 'American Hagwon,' will explore Korean education obsession

- Actor Timothy Busfield ordered held without bond in New Mexico child sex abuse case

- Royal Opera sees generation change as Jakub Hrůša and Speranza Scappucci come in

- Julio Iglesias accused of sexual assault in Caribbean as Spanish prosecutors study the allegations

- Fanatics debuts Fanatics Studios with Olympics, Tom Brady and ESPN at Intuit Dome

- Warm up with creamy rutabaga, parsnip and cheddar soup

- Kim Gordon returns with defiant new solo album, 'Play Me': 'It does feel like an evolution'

Sorokin's NHL-leading fifth shutout and Duclair's late goal lift Islanders over Oilers 1-0

- Marino scores in third period to give Utah Mammoth 2-1 win over Dallas Stars

- Backlund and Sharangovich lead Flames to 3-1 road win over Blackhawks

- Defending champion Nick Taylor tied for Sony Open lead

- Scheifele has 4 points as Jets beat Wild 6-2 for 4th straight win

- Kyle Tucker agrees to a $240 million, 4-year contract with the World Series champion Dodgers

- Mavericks rookie star Cooper Flagg out against Jazz because of ankle injury

- Maple Leafs' William Nylander exits game with lower-body injury

- Thompson scores 26 points, moves up 3-point list, as Flagg-less Mavericks cruise past Jazz, 144-122

- After retiring Zdeno Chara's No. 33, Bruins get off to quick start and beat Kraken 4-2

Join the 2026 Dog Adoption Carnival This Weekend at Cyberport: Free Admission and Fun Activities!

- Hong Kong Hosts 2026 WAIC UP! Summit: Embracing AI's Future Together

- John Lee Welcomes Global AI Leaders to Inaugural WAIC UP! Summit in Hong Kong

- Government Reappoints Professor Thomas Ho as Chair of Construction Industry Council, Announces New Members

- Hong Kong Customs Seizes 19,000 Counterfeit Goods Worth $14 Million in Major Operation

- Hong Kong Sees Record Company Registrations in 2025, Totaling Over 1.5 Million

- Six illegal workers and an employer arrested in Hong Kong's anti-illegal worker operation Contribute

- Tai Po Fire Identifies 168 Victims, Police Confirm No Unidentified Remains

- Health Officials from Mainland, Hong Kong, and Macao Meet to Discuss Medical Innovations and Public Health Strategies

- HKMA Warns Public About Recent Banking Scams and Fraudulent Websites

U.S. tariffs plunge Lesotho's textile industry into crisis

- Japanese PM's erroneous remarks on China's Taiwan undermine regional stability

- Palestinian death toll in Gaza rises to 71,439: health authorities

- Russia, Ukraine update battle reports

- US source of region's instability: Iranian residents

- UNGA President warns global multilateral system "under attack"

- Japan's main opposition CDPJ, Komeito agree to form new party

- Japanese people rally against PM's erroneous remarks, military expansion

- US intentions in Greenland violates Int'l law, targets oil: Spanish expert

- Former Iranian VP warns foreign interference undermines demands of real protesters

Category · News

Sorokin's NHL-leading fifth shutout and Duclair's late goal lift Islanders over Oilers 1-0

Inside a year of firings that have shaken the Trump Justice Department: 'A great deal of fear'

How the White House and governors want to fix AI-driven power shortages and price spikes

Inside a year of firings that have shaken the Trump Justice Department: 'A great deal of fear'

Trump isn't waiting for future generations to name things after him. It's happening now

Judge orders release of Liberian man arrested in Minneapolis by agents with a battering ram

Marino scores in third period to give Utah Mammoth 2-1 win over Dallas Stars

Backlund and Sharangovich lead Flames to 3-1 road win over Blackhawks

Kerry Launches 2026 Supplements Taste Charts: Defining the Next Era of Flavour in Supplements and Sports Nutrition

Defending champion Nick Taylor tied for Sony Open lead

Join the 2026 Dog Adoption Carnival This Weekend at Cyberport: Free Admission and Fun Activities!

Scheifele has 4 points as Jets beat Wild 6-2 for 4th straight win

Kyle Tucker agrees to a $240 million, 4-year contract with the World Series champion Dodgers

Fire breaks out in Seoul's last-remaining shanty town

Coda and Unity to enable out-of-app monetization for game developers globally

NSF Launches Retail Food Safety Audits Program in ASEAN and Australia

Crude futures settle lower

Mavericks rookie star Cooper Flagg out against Jazz because of ankle injury

Maple Leafs' William Nylander exits game with lower-body injury

Thompson scores 26 points, moves up 3-point list, as Flagg-less Mavericks cruise past Jazz, 144-122

CIOs Face an Accelerating Gap as Adaptive IT Leadership in the Spotlight at Info-Tech LIVE 2026 in Brisbane

Middle East allies in blitz of diplomacy urged Trump to hold off on Iran strikes, diplomat says

Venezuela's Machado says she presented her Nobel Peace Prize to Trump during their meeting

China to expand high-standard opening-up to foster win-win cooperation: minister

Chow Tai Fook Jewellery Launches Next Phase of International Expansion with New Bangkok Opening and Appointment of Global Brand Ambassador

Hong Kong Hosts 2026 WAIC UP! Summit: Embracing AI's Future Together

After retiring Zdeno Chara's No. 33, Bruins get off to quick start and beat Kraken 4-2

Warriors coach Steve Kerr chatted with Jonathan Kuminga about his uncertain situation

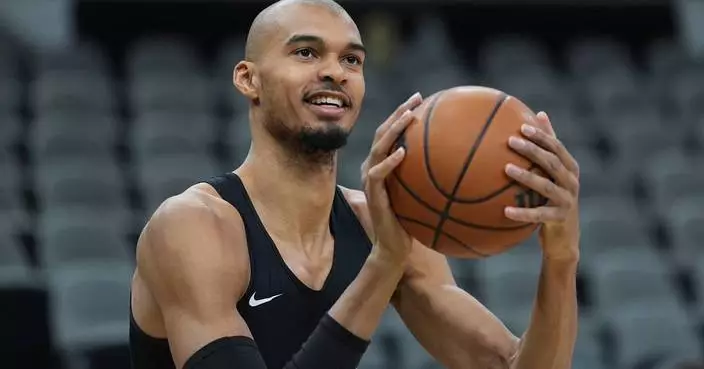

Wembanyama returns from injury scare to fuel Spurs past Bucks, 119-101

BMO China president highlights growth opportunities in Canada-China trade

Harnessing the Power of Sports: Orange Lion Sports Leads the Way in Driving the Emerging Trend of "Racecation"

Sharks' 3-goal second period keys 3-2 victory over Capitals

Simons scores 39 points off the bench, Brown adds 27 and Celtics rally to stun Heat 119-114

Dreame Debuts AI-Powered Whole-home Smart Ecosystem at CES 2026, Earning Multiple Industry Awards

Fantôme Rapport Launches in English — A Romance, Horror, and Mystery Adventure Aboard a Ghostly Luxury Liner

GIGABYTE Showcases Practical AI TOP Utility for Local AI Applications at CES 2026

Infobip strengthens leadership to drive growth and innovation

John Lee Welcomes Global AI Leaders to Inaugural WAIC UP! Summit in Hong Kong

Government Reappoints Professor Thomas Ho as Chair of Construction Industry Council, Announces New Members

Trump threatens to use the Insurrection Act to end protests in Minneapolis

Hong Kong Customs Seizes 19,000 Counterfeit Goods Worth $14 Million in Major Operation

Boston Bruins retire Zdeno Chara's No. 33, honoring the giant defenseman who led 2011 Cup victory

Blakes scores 38 points, No. 5 Vanderbilt beats Mississippi State for first 18-0 start

Xi to meet Canadian PM

Adin Hill returns to Golden Knights after nearly 3 months, Carter Hart goes on IR

TVBS and Disney+ Achieve Record-Breaking Success with 40th Golden Disc Awards in Taiwan

ZWIE and The Education University of Hong Kong Sign Memorandum of Cooperation to Promote Exchange and Deepen Collaboration

The Latest: UN Security Council discusses Iran's deadly protests after US request

Point Hope Announces Launch of the Anchor Generational Assets Fund

Trump's Insurrection Act threat stands out against the law's long history

Athletes Unlimited announces star-studded roster for 5th season of women's basketball

NIA Highlights Key Innovation Trends for 2026, Spotlighting Innovation Policies Driving Thailand’s Economy and Society

Panduit Strengthens Commitment to Customer Excellence with Appointment of Holly Garcia to Chief Commercial Officer

Federal immigration agents filmed dragging a woman from her car in Minneapolis

Wembanyama returns after early injury in Spurs vs. Bucks game

China calls for restraint at UNSC meeting on Iran situation

Venezuela’s new leader calls for opening oil industry to foreign investment and warmer US ties

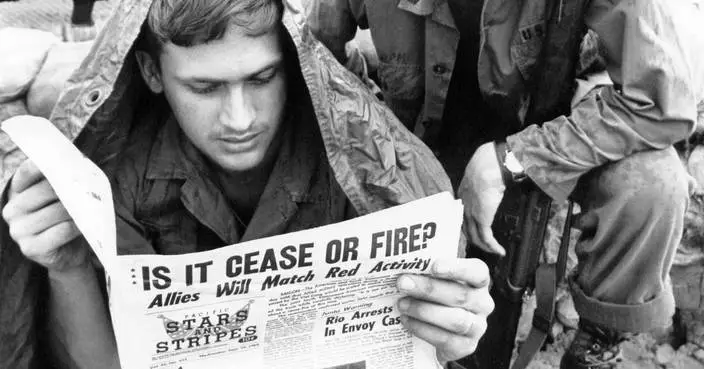

Defense Department says military newspaper Stars and Stripes must eliminate 'woke distractions'

American Ben Shelton heads to the Australian Open after losing in the Auckland quarterfinals

Christian McCaffrey, Aaron Jones and Jake Ferguson are finalists for NFL's Salute to Service Award

Hong Kong Sees Record Company Registrations in 2025, Totaling Over 1.5 Million

Ravens interview former Dolphins coach Mike McDaniel for their coaching vacancy

Seahawks don't expect many surprises when they host 49ers in playoffs, 2 weeks after last meeting

MindHYVE.ai™ and The Open University of Kenya Announce Strategic Collaboration on AI-Powered Learning and Academic Innovation

International media flock to Greenland as Trump turns the Arctic island into a geopolitical hot spot

MOVA Launches Cleaning Solutions in Silicon Valley: Finding Answers for Premium Cleaning Through Pragmatic Innovation

MOVA Unveils 'the M∞VA Universe' at Silicon Valley Launch, Positioning as a Global Premium AI Smart Living Leader

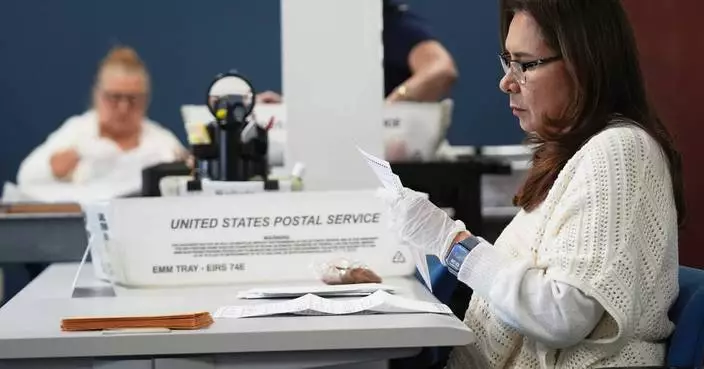

Senators worry that US Postal Service changes could disenfranchise voters who cast ballots by mail

Trump announces outlines of health care plan he wants Congress to consider

Alaska court weighs voter misconduct charges in case that casts light on status of American Samoans

Kathleen Kennedy, steward of 'Star Wars,' steps down from Lucasfilm

NYC nurses on strike resume negotiations with hospitals on 4th day

China's commercial rocket launches new satellites from sea

Pitcher Ryan Weathers just got out of sauna when he learned of trade to the Yankees

New Oceania soccer competition has a 2029 Club World Cup spot as the winner's reward

Photos show Venezuela caught between Machado’s diplomacy and Rodríguez’s rule

Pats eye 1st trip to AFC title game in 7 years against Texans team looking for 1st appearance

Bills face Broncos in Denver's first home playoff game since 2015 season

Matthew Stafford and Rams visit Caleb Williams and Bears in matchup of high-powered offenses

Seahawks, 49ers preparing to meet for 2nd time in 3 weeks in NFC divisional round matchup

As Additive-Free Spirits Surge, Rum Becomes the Next Category Under the Microscope

Rams collide with resurgent Bears in divisional round matchup featuring high-powered offenses

Eagles' Sirianni and Roseman offer few details on ouster of Patullo and what they want in new OC

Versatile Willi Castro and Rockies agree to $12.8 million, 2-year deal, AP source says